At 3 a.m. on a recent Tuesday, Megan Sampson dreaded the idea of missing a day teaching so soon in the school year. She wanted her new students at Wauwatosa East High School to stay on track in their education.

But Sampson was in agony. She suffers from a gynecological disease that can cause debilitating pain when tissue similar to what lines the uterus grows in other places, too.

She considered taking a powerful painkiller kept from a past surgery or calling in for a substitute teacher.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“That’s a really demoralizing thought to have. That you’re in so much pain, a stranger is better off in front of your students,” Sampson said. “It’s emotional, and it makes me feel like I’m not as good of a teacher.“

Sampson is among an estimated 10 percent of women and girls of reproductive age with endometriosis. People with the disease often struggle to receive a diagnosis, which can delay treatment.

A new documentary and Wisconsin Public Radio interviews underscore that women sometimes must visit several doctors and wait years before obtaining clarity on the cause of their pain. They report doctors doubting or minimizing their pain, as well.

“Unfortunately, we haven’t made nearly as much progress as we would like,” said Dr. Camille Ladanyi, a gynecologic surgeon at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. “We are unable to really, truly individualize care as much as we would like to as providers.”

Sampson ultimately called in a substitute teacher due to her pain.

“It was bad,” she said. “It was really bad.”

Doubted at the doctor

Shannon Cohn first noticed symptoms of endometriosis at age 16. But it took 13 years to hear the disease’s name, she said. From her pediatrician and school nurse to her primary care provider, doctors struggled to help her find answers.

“No one knew really what was going on,” Cohn said recently on Wisconsin Public Radio’s “Central Time.” “No one put the pieces together.”

Cohn is a documentary producer and director. Her latest film, “Below the Belt,” seeks to raise awareness of endometriosis by sharing the stories of four women with the disease. Cohn said she partially produced the film for her two daughters, who are at higher risk of having endometriosis, too.

“Endometriosis is a perfect, awful storm,” Cohn said. “It’s about menstrual taboo and societal taboo of talking about below-the-belt issues in women. It’s about gender bias. It’s about racial bias. It’s about institutional and financial barriers to care.”

Dr. Soyini Hawkins, founder of the Fibroid and Pelvic Wellness Center of Georgia, estimates the average diagnosis takes seven to 10 years. However, for Black and Hispanic women, it could take twice as long, she said at a recent American Journal of Managed Care event.

Ladanyi directs the minimally invasive gynecological surgery section of UW-Madison’s medical school. Appearing on “Central Time” with Cohn, Ladanyi said endometriosis patients show very different symptoms at varying degrees of severity. Many have pain. Some experience abnormal bleeding patterns, gastrointestinal problems, fatigue, depression or anxiety.

Sampson said she always had painful periods as a teenager. She missed days of school. She started taking birth control pills at age 16 to help manage pain. Sampson said she went through five doctors as a young adult and none adequately addressed her concerns.

Women, transgender people and people of color are most likely to be doubted by doctors, said Karen Lutfey Spencer, who studies patient-provider relationships and health disparities. Medicine has a long history of collecting data based on men, male animals and male cells, Spencer recently said on “Central Time.”

“We kind of assumed for a long time, ‘Well that happens one way in men. Surely it carries over to all these other populations,’” she said. “What we’re finding out is if something shows up in a way that is not the way it shows up in men, then it introduces a certain amount of uncertainty for doctors. And when there’s uncertainty, it invites people to fill in the gaps with stereotypes and bias.”

Spencer, who works at the University of Colorado Denver, recommends patients keep a pain diary — a written record of their medical experiences. Going with someone to the doctor could be helpful, too. Sampson and her husband advocated for doctors to get Sampson on their schedules. And having the second voice seemed to help.

Endometriosis can harm the body beyond its reproductive organs. Ladanyi said doctors must work across specialties to identify potential danger. Otherwise, patients might bounce around from provider to provider.

About 30 years ago, endometriosis required Melani Fay of Onalaska to be hospitalized for nine days and doctors had to remove her lung lining. Her lung had collapsed because endometriosis perforated her diaphragm.

Fay said many friends shared their experiences with endometriosis after her hospitalization and the disease seemed much more common than how often it was being discussed.

“It’s a women’s problem,” Fay said. “I think that is part of why it hasn’t been given a lot of attention.”

‘Not just in my head’

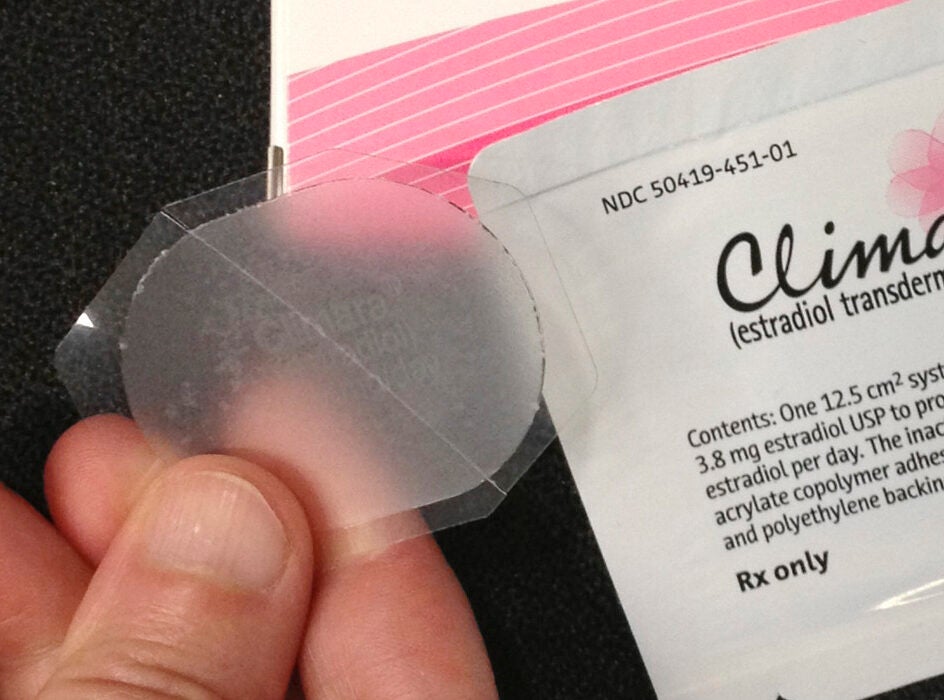

While surgery is considered the “gold standard” to confirm endometriosis, Ladanyi said treatment may begin sooner under a presumed diagnosis. Hormonal suppression, pain psychology or pelvic floor therapy are a few methods used to address symptoms.

Surgical treatments involve removing tissue or using heat to destroy it. But surgery can be expensive, particularly if procedures are out of network, said Cohn, the documentary producer and director.

“A lot of times, they have to pay out of pocket,” Cohn said. “They’re using credit cards. They’re using savings to access this type of surgery, which is evidence of a larger problem — a larger broken system that we all can identify with.”

Women are becoming more comfortable discussing endometriosis and other matters affecting menstruation, Cohn said. “Below the Belt” is being released globally in the coming months. Cohn hopes the film raises awareness of the disease in health care so providers more quickly consider endometriosis, deliver diagnoses and offer treatments.

“Girls hear the word at 13 instead of 23 or 33,” Cohn said.

Ladanyi hopes more awareness of the disease helps research efforts, too. She often hears from patients who are eager to be a part of research.

“It’s just a matter of trying to continue the efforts, helping people to understand how important this is and how much it’s impacting the quality of their life,” she said. “There’s just so much bias, especially when it comes to pain. So, it’s easy for some of these people to just really be disregarded.“

A laparoscopic surgery last year confirmed Sampson’s endometriosis. She felt vindicated.

“That was a big deal,” Sampson said. “I felt like I wasn’t crazy. There is a reason for all this pain. It’s not just in my head.”

Sampson is exploring fertility treatments and seeing a Green Bay specialist outside her insurance coverage. She plans to have another surgery later this year to treat her endometriosis.

Sampson expects to miss about a day of teaching per month due to her pain. She started talking about the disease with students last year so they understood her absences. Those conversations also spurred others to share their experiences.

“It’s just not easy to talk about this kind of pain, but it doesn’t make it hurt any less,” she said. “There are a lot of women that just struggle in silence … The better we can do in learning about this, the more women don’t feel like they have to just be hiding with this really bad pain.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.