Wisconsin U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson had just seven minutes to ask key members of law enforcement questions about an attack on the U.S. Capitol that was unprecedented in modern American history.

It’s not much time, but it was the rule for rank-and-file lawmakers at the Feb. 23 joint hearing of the Senate’s homeland security and rules committees, where witnesses included the former chief of the U.S. Capitol Police, the acting police chief for Washington, D.C. and the former U.S. House and Senate sergeants at arms.

Johnson’s colleagues used their moments in the spotlight to rattle off as many as a dozen questions to witnesses, pinning them down on what they knew before the Jan. 6 insurrection and how they reacted once the siege of the Capitol began.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In contrast, Johnson, a Republican, used his allotted time to read an article depicting most of the crowd that rallied in Washington on Jan. 6 as “jovial” and “friendly.”

“Many of the marchers were families with small children,” Johnson read from an account in the conservative Federalist magazine. “Many were elderly, overweight or just plain tired or frail — traits not typically attributed to the riot-prone.”

The article Johnson read blamed four groups for the insurrection: “plainclothes militants, agents-provocateurs, fake Trump protesters” and a “disciplined, uniformed column of attackers.” The article’s author said he did not see any “fake Trump protesters” commit violence, and to date, there has been no evidence that fake protesters or Antifa were behind the siege.

But Johnson didn’t mention that at the hearing, instead lumping all four groups together and offering his own assertion.

“I think these are the people that probably planned this,” Johnson said.

Johnson’s comments riled many in the room that day, who had only weeks earlier been whisked to secure locations when rioters overwhelmed police and overtook the Capitol, including the Senate chamber.

But they fit a pattern for Johnson, who had also recently downplayed the severity of the insurrection and amplified former President Donald Trump’s false claims that elections were “stolen” in key swing states, including Wisconsin.

“He has been saying and doing things that just can’t be justified,” said Larry Sabato, director of the Center for Politics at the University of Virginia. “I think a lot of people have been stunned that he would go as far as he has.”

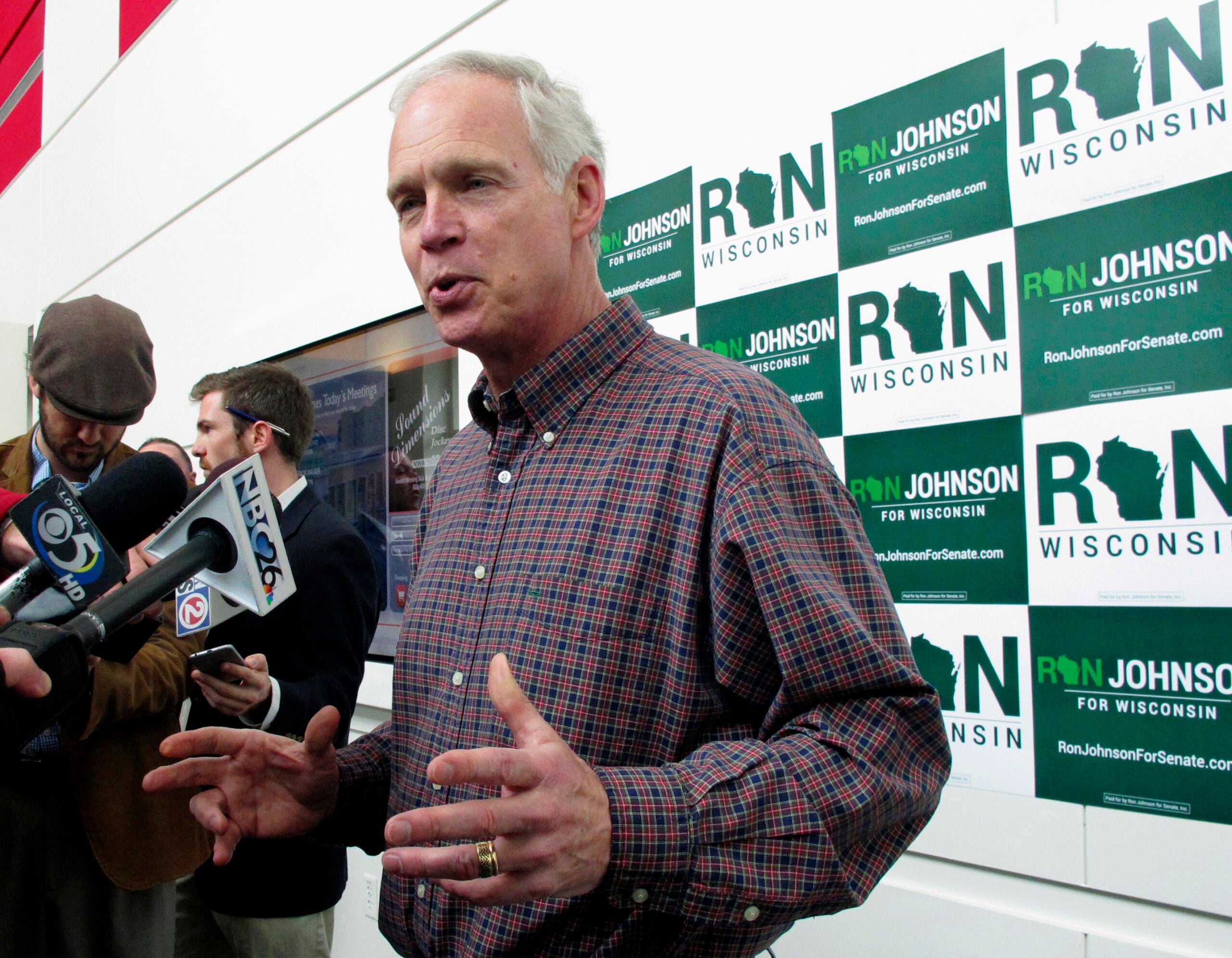

Johnson’s comments also come as he is considering a campaign for a third term in the U.S. Senate, at a time when Trump remains the Republican Party’s standard-bearer.

“I know the senator,” said A.B. Stoddard, an associate editor and columnist at Real Clear Politics. “He is smart enough, and I know that he knows this stuff isn’t true.”

“He’s basically going where the wind is blowing,” Stoddard said. “His voters are asking for this, and he wants that job.”

‘This Didn’t Seem Like An Armed Insurrection To Me’

Johnson’s comments in committee came a couple weeks after he made similar remarks on conservative talk radio in Wisconsin.

During a Feb. 15 interview with WISN-AM radio’s Jay Weber, Johnson answered questions about Trump’s acquittal in the latest impeachment trial. Weber thought the trial failed to show that Trump incited the Capitol riot. Johnson agreed.

It was near the end of the interview when Johnson decided to pivot.

“This will get me in trouble,” Johnson said. “But I don’t care.”

Johnson said he condemned what happened, calling the insurrection “reprehensible.” But he proceeded to question how the event was being portrayed.

“This didn’t seem like an armed insurrection to me,” Johnson said. “When you think of armed, don’t you think of firearms?”

By this time, Johnson had seen impeachment trial video of the violent clashes at the Capitol and had access to widespread reporting of rioters who hurled everything from rebar to firecrackers at police while soaking them with cannisters of bear spray.

Richard Barnett, the Arkansas man who was famously photographed sitting at a desk in U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s office during the siege, has been charged with carrying a stun gun inside the Capitol. Eric Munchel, the man allegedly photographed in the Senate chamber carrying zip tie handcuffs, allegedly stashed weapons outside the building before he entered.

While there have been no reports of rioters shooting anyone on Jan. 6, there were ample signs that some were considering it. Police allegedly found two guns, a crossbow, hundreds of rounds of ammunition and 11 Molotov cocktails in one truck parked just blocks from the Capitol. Another man who arrived in Washington the day after the insurrection allegedly bragged in text messages that he would shoot Pelosi on live TV.

Officers who defended the Capitol on Jan. 6 have not minced words about their experiences.

“They ripped my badge from me and people were trying to grab my gun,” said Washington, D.C. Police Officer Mike Fanone, who was dragged from a Capitol doorway and beaten. “I remember guys chanting ‘Kill him with his own gun.’ I was tased — I think about a half-dozen times — on the back of my neck.”

Former U.S. Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund, who resigned after the insurrection, said people came “prepared for war.”

“I witnessed insurgents beating police officers with fists, pipes, sticks, bats, metal barricades and flag poles,” Sund said.

Rioters who breached the Capitol chanted “Hang Mike Pence” as the former vice president was preparing to oversee the Electoral College count affirming President Joe Biden’s Victory. A Black officer said he was repeatedly called the n-word by people in the crowd.

Four protesters died on the day of the Jan 6. insurrection, including one who was shot by police while attempting to storm a room where lawmakers had been present just moments earlier. One police officer died from injuries sustained in the riot. Two other officers who defended the Capitol that day later committed suicide.

Johnson’s Comments Turn Heads

Even in the hyper-partisan world of Washington politics, where attention-grabbing statements are a way of life, Johnson’s recent comments have turned heads.

“They were out there with Trump merch, screaming ‘Fight for Trump’ and calling the cops ‘traitors,’” said Stoddard. “So with the video that we have, Sen. Johnson’s comments are ridiculous.”

“It was an historic event,” said Sabato. “And it’s going to be remembered a lot longer than Sen. Johnson is.”

“It was a serious, serious event in our history,” said Christian Schneider, a conservative writer and columnist who has been a vocal Trump critic. “People died. And so maybe pretending as if it wasn’t an armed insurrection might not be the best thing.”

Schneider is a former Republican staffer at the Wisconsin state Capitol who, in 2010, was writing for the conservative Wisconsin Policy Research Institute, now the Badger Institute.

Schneider’s GOP connections at the time gave him access to the inner-workings of Johnson’s first Senate campaign against former Democratic U.S. Sen. Russ Feingold, where staffers held hours of behind-the-scenes training sessions to try to get Johnson to speak more cautiously in public.

It didn’t work. Johnson refused to back down on some topics, like defending the rights of oil company British Petroleum even as it was being attacked for causing a catastrophic oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico. And Johnson still brought up other issues without warning, like when he told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel editorial board that sunspots were to blame for global warming, not human activity.

“His campaign staff was just pulling their hair out, saying, you know, ‘Ron, you can’t say these things,’” Schneider said. “But he eventually did and eventually won. So I think the thing that that taught him is to trust his own instincts and not really listen to the ‘political professionals.’”

Schneider sees this as a common thread for Johnson’s Senate career.

“He’s saying what he wants to say, and nobody’s going to tell him any different,” Schneider said. “He thinks he navigated his campaigns in the past based on his own intuition. And that’s what he’s going to keep doing.”

Stoddard, with Real Clear Politics, said Johnson came to Congress as a businessman looking to focus on the national debt as a policy issue. But somewhere along the line, Stoddard thinks Johnson realized his voters aren’t interested in the debt, but they love Trump, and want Republicans who share Trump’s style.

“Which is to always stay on offense,” Stoddard said. “To always keep fighting, to be confrontational, to ‘own the libs,’ confront the media, pick fights and raise hell.”

In Johnson’s case, Stoddard remains convinced that what he’s saying about the insurrection is about appeasing those voters, even if it means mischaracterizing what happened.

“He knows exactly what was happening outside and then inside — that Antifa wasn’t involved. That these people were coming for the cops,” Stoddard said. “He’s embracing this stuff in a performative way.”

A Possible Third Term

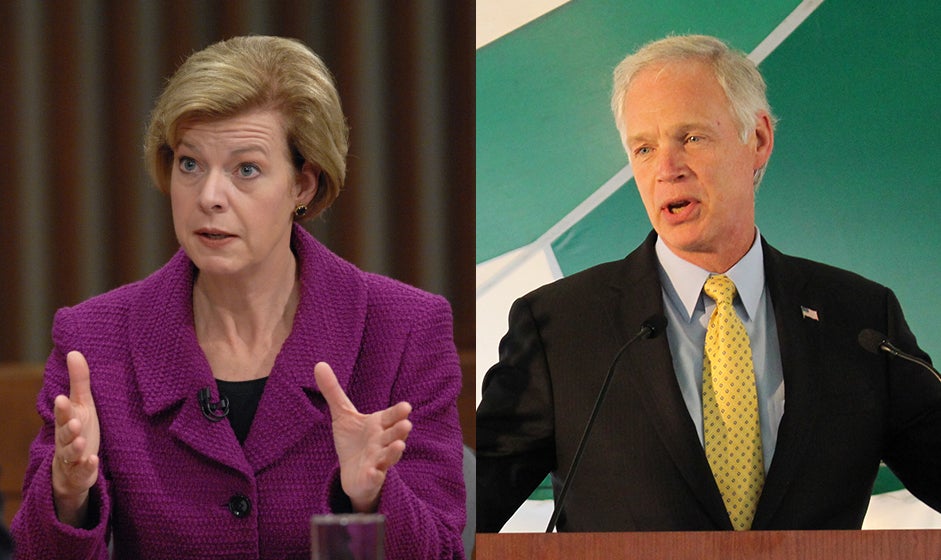

Democrats have taken notice of Johnson’s latest remarks in a big way as he considers a third term in the Senate.

Last week, Pelosi suggested Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Kentucky, was taking his cues from Johnson when it comes to investigating the Capitol insurrection.

“Ron Johnson seems to be taking the lead on what the scope would be of how we look at protecting our country from domestic terrorism,” Pelosi said during a press conference last week.

It wasn’t exactly a compliment from one of the nation’s most powerful Democrats, who initially made it sound like she couldn’t remember Johnson’s first name, referring to the 10-year incumbent as “Don” Johnson of “Miami Vice” fame. (Just a month earlier, Johnson had wondered aloud on Fox News — without evidence — whether Pelosi was using the impeachment to deflect attention from what she knew about the insurrection. “I’m suspicious,” Johnson said at the time).

With Trump no longer in the White House, and much less visible for the time being, Johnson has emerged as one of the national figures who motivate Democrats, particularly in Wisconsin.

“Ron Johnson has become Wisconsin’s own Ted Cruz,” said Wisconsin Democratic Party Chair Ben Wikler, referring to the outspoken Texas Republican senator. “He is lighting a fire under our grassroots.”

Already, a handful of Democrats are running for Johnson’s seat. They include Outagamie County Executive Tom Nelson, Bucks executive Mark Lasry and Wausau doctor Gillian Battino. Other Democrats considering the race include Treasurer Sarah Godlewski and La Crosse U.S. Rep. Ron Kind.

Six years ago, Johnson said unequivocally that he would not seek a third term in office during the closing days of his 2016 campaign against Feingold, who served three terms in the Senate before Johnson defeated him twice.

“This will be my last term,” Johnson said during a debate with Feingold. “I’ll never vote (with) my reelection in mind ’cause I’ll never stand for reelection again. I don’t know how many times Sen. Feingold’s going to run for reelection.”

Less than three years later, Johnson had changed his tune, opening the door to running either for a third term in the Senate or possibly even governor.

“The world changes. Situations change. So you just never say never,” Johnson said in 2019.

There are reasons Johnson’s possible candidacy is getting so much attention beyond what he’s saying about the insurrection, the 2020 election and other topics.

“Ron Johnson is — if he chooses to run again — the most vulnerable Republican on the map,” said Jessica Taylor, the Senate editor for the Cook Political Report. “He is the only Republican incumbent that is running for reelection in a state that voted for the opposite party presidential candidate.”

Taylor notes that Johnson’s race was viewed similarly in 2016 when he defied expectations and won. Johnson actually received more votes than Trump that year.

In a state as closely divided as Wisconsin, Sabato, with the University of Virginia, expects almost any candidate will keep the Senate race tight, Johnson included.

“His greatest advantage is he has an ‘R’ next to his name,” Sabato said. “And if the election year is Republican, he’s going to win.”

Conventional wisdom seems to hold that Johnson will indeed run again, in part because of everything he’s been saying.

“I can’t understand why he would take some of these pro-Trump positions that he has if he wasn’t eyeing up a run in 2022,” Schneider, the conservative columnist, said.

Stoddard said that like other Republicans on the ballot in 2022, Johnson is catering to Trump.

“You have to embrace Trump to keep your job,” said Stoddard. “What is their goal? Obviously, it’s to keep their job.”

Stoddard said that includes embracing Trump’s false assertion that he won the election, a claim Trump continued to make at his recent speech at the Conservative Political Action Conference, or CPAC.

Sabato agrees.

“He is helping Donald Trump to sell the big lie and he has for months now,” Sabato said.

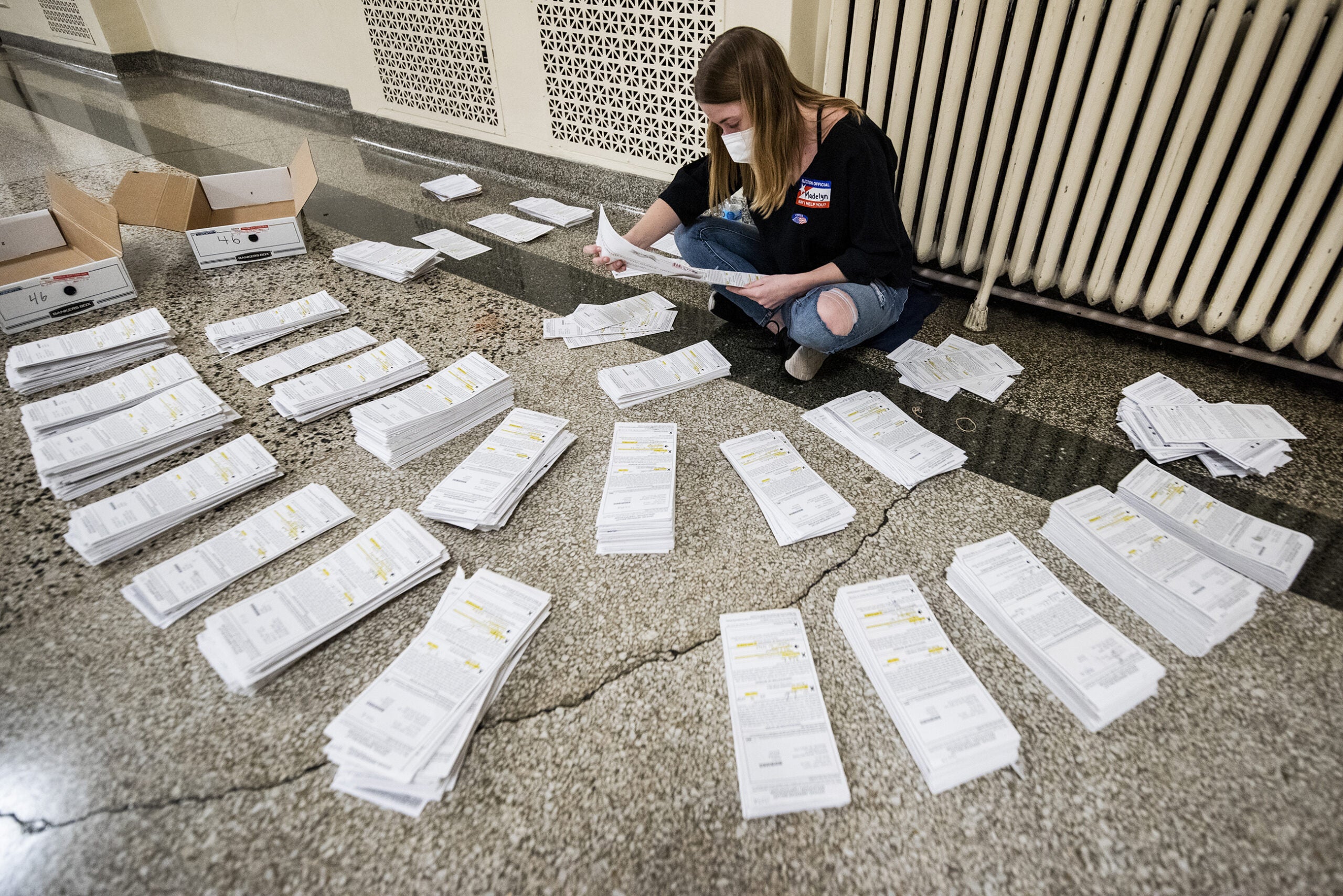

The 2020 Election Fallout

While Johnson’s office did not respond to a request for an interview for this story, the senator has disputed the idea elsewhere that he was lying about the election or trying to overturn its results.

Certainly, his position is harder to summarize than Trump’s. Johnson has acknowledged Joe Biden’s victory in Wisconsin. At the same time, Johnson has elevated theories that have cast doubt on the election’s results.

In December, after Trump’s campaign had lost its Wisconsin election lawsuits in both state and federal courts, Johnson held a hearing where he invited one of the president’s lawyers, Jim Troupis, to testify. Troupis proceeded to assert the same theories that had been rejected in multiple courts.

Troupis testified that “more than 200,000” Wisconsin residents did not vote legally in Wisconsin, a number that included more than 170,000 residents who voted early at their local clerk’s office using a form that had been in place for more than a decade. Troupis himself was among those voters.

Not a single member of Wisconsin’s Supreme Court gave any indication that they would have overturned this block of voters, and when Troupis appealed the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court, he abandoned this argument altogether.

But not at Johnson’s hearing. There, Troupis claimed “more than 200,000” illegal votes, and Johnson did not press him for details. Johnson’s office later posted a video of Troupis’ speech to the senator’s official Twitter account.

Trump, who was not yet banned from Twitter, then retweeted the video to his nearly 90 million followers.

On Jan. 6, before the siege of the Capitol, Johnson was one of eight U.S. senators who signed an objection to Arizona’s electors. Hours after the siege, lawmakers debated Arizona’s election, but Johnson ultimately voted to uphold the state’s results.

He still issued a statement after the vote, in which he made repeated allusions, without evidence, to a variety of voter fraud, calling the people who had lost confidence in the election “patriots” and saying they “heard” reports of everything from “large Democrat-controlled counties” dumping ballots to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg spending money to “increase Democrat turnout in Democrat-controlled jurisdictions.”

“Is it any wonder that so many have lost confidence in the fairness of our election system and question the legitimacy of the result?” Johnson said in the statement.

It fit another pattern for Johnson, who has shown a penchant for offering provocative statements or questions without entirely saying where he stands on an issue.

After he read the account of agitators or “fake Trump” protesters at the Feb. 23 joint Senate hearing, Johnson didn’t say precisely what he thought about the account.

“A lot of press reports are assuming, imputing all kinds of conclusions,” Johnson told the New York Times. “They’re saying I’m saying things that I’m not saying at all. All I’m saying at this point in time is we need to ask a lot of questions.”

On Wednesday of this week, Johnson’s office pointed reporters to a new video of Johnson from another committee hearing on the insurrection. At the latest hearing, Johnson still read from portions of the same eyewitness account, but he also peppered witnesses with a series of specific, detail-oriented questions, a sharp contrast to his moment in the spotlight a week earlier.

Then, just hours later, Johnson was at the center of another storm.

This one was widely reported as being Johnson’s idea. He promised to employ a rarely-used parliamentary maneuver to slow down the passage of Biden’s $1.9 billion COVID-19 relief bill.

“I’m going to make them read that thing,” Johnson told WISN-AM. “I’m going to keep objecting.”

Johnson estimated reading the entire bill aloud would take up to 10 hours, after which he would offer as many amendments as he could to try to cut the cost of the bill. At the very least, he could stall it.

The move prompted an immediate outcry from Democrats who said the decision would delay $1,400 payments to families who were suffering from the pandemic.

It was familiar territory for Johnson, a senator who these days jumps quickly from one acrimonious conflict to the next.

Editor’s note: This story was updated to clarify that Richard Barnett was photographed sitting at a desk in Nancy Pelosi’s office, not at Pelosi’s personal desk.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.