Chanel Clark returned to work six weeks and one day after delivering her son Thane in 2013. The Madison child care provider had coached countless parents on such transitions yet struggled to navigate her own journey as a new working parent.

“It was way too soon. I was not ready for it at all, not even a little — and I knew what to expect,” Clark said.

Repeated sobbing marked her first day back at work at Little Chicks Learning Academy — a highly rated, nationally accredited day care that she couldn’t afford for her own child. Tears flowed as she dropped Thane off to an unregulated in-home center that charged $150 per week, far less than Little Chicks. Clark recalls practically sprinting out of work to pick him up after her shift — to breathe in his newborn smell again.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Although Thane is now a healthy 9-year-old and the family cultivated and maintains a deep, supportive relationship with his first in-home provider, Clark wished early on that she could enroll him at Little Chicks, where she made $12 an hour before gradually rising to executive director.

“That’s a tough nugget to swallow,” she said. “Like I’m good enough to teach this and to offer this, but I can’t actually give it to my own kid.”

Despite not feeling ready, Clark had no choice but to return to work. Her family needed the income. She wasn’t paid while on leave, and her husband took off just one unpaid week from his job at SSM Health St. Mary’s Hospital in Madison. They burned through savings and leaned heavily on credit cards during Clark’s short time off.

Such are the excruciating choices new parents face across Wisconsin and the country. The tradeoffs affect career prospects, financial stability, mental health and infant development — while shaping the broader economy.

Parents of kids of all ages struggle to afford child care due to the broken economics of a heavily regulated industry that pays its workers less than $27,000 a year yet still must charge high rates to cover costs. But the earliest weeks of parenting are especially crucial. Day care for infants is toughest to find, forcing many parents to forfeit their paychecks or miss out on valuable postpartum recovery and bonding. Recovering from a cesarean section — the delivery mode for about one-third of births — generally takes about six weeks.

That means many parents — most often mothers — stay home those first several weeks, risking harm to their careers. Like so many challenges, lower-income workers face the most stress, particularly women of color. And child care obstacles are crimping the workforce as employers are struggling to attract workers.

Expanding paid leave benefits could ease parental pain, improve the health of infants and deliver long-term benefits for employers, a growing body of research shows.

Nearly 30 percent of working women in the United States pause paid work when they have a child, according to research by Kelly Jones, an assistant professor of economics at American University, and doctoral candidate Britni Wilcher. Paid leave programs in California and New Jersey increased the labor participation rate for up to five years following a birth.

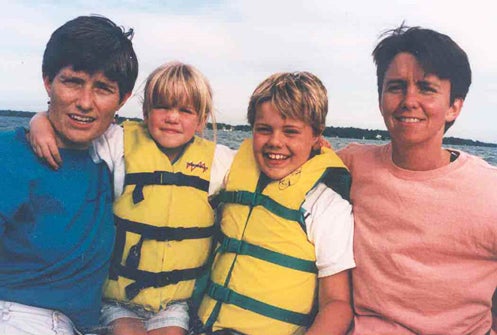

[[{“fid”:”1650581″,”view_mode”:”embed_landscape”,”fields”:{“format”:”embed_landscape”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EOffering%20a%20parent%20six%2C%20eight%20or%2012%20weeks%20of%20leave%20following%20a%20birth%20may%20seem%20small%2C%20says%20Kelly%20Jones%2C%20an%20assistant%20professor%20of%20economics%20at%20American%20University.%20But%20the%20implications%20%22can%20reverberate%20throughout%20the%20rest%20of%20her%20working%20life.%22%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Kelly%20Jones%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Economist Kelly Jones”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Economist Kelly Jones”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“6”:{“format”:”embed_landscape”,”alignment”:”right”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EOffering%20a%20parent%20six%2C%20eight%20or%2012%20weeks%20of%20leave%20following%20a%20birth%20may%20seem%20small%2C%20says%20Kelly%20Jones%2C%20an%20assistant%20professor%20of%20economics%20at%20American%20University.%20But%20the%20implications%20%22can%20reverberate%20throughout%20the%20rest%20of%20her%20working%20life.%22%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Kelly%20Jones%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”Economist Kelly Jones”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”Economist Kelly Jones”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”Economist Kelly Jones”,”title”:”Economist Kelly Jones”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-landscape media-wysiwyg-align-right”,”data-delta”:”6″}}]]”There’s serious inertia in these decisions,” Jones said. “Even if women are leaving with the intention of it being temporary, many times it actually ends up being much longer term than they expected.”

Despite broad public support, the U.S. is the only country among 41 European Union and Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development nations that fails to guarantee paid parental leave. Access is slowly growing, but just 1 in 4 American workers had the benefit in 2021, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In Congress, President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better Act would have guaranteed paid family leave to most workers. But negotiations shrunk those benefits from 12 to four weeks, and the legislation was derailed in the Senate after clearing the House in November.

Some states have taken their own action, but Wisconsin’s Republican-controlled Legislature has not advanced recent proposals to broaden access.

Fewer women in workforce

The second half of the 20th century saw record numbers of women leap into the U.S. workforce as cultural shifts unlocked opportunities. But the share of women working for pay has dipped since peaking at 60 percent in 1999 — now hovering around 56 percent, according to the federal statistics bureau.

More working women mean more economic growth, said Betsey Stevenson, a University of Michigan professor of economics and public policy. But the COVID-19 pandemic worsened challenges that predated the public health crisis, Stevenson testified during an October hearing of Congress’ Joint Economic Committee.

“The challenges that parents faced during the pandemic were not unique to the recession,” Stevenson testified. “Instead, they highlight our failure to adapt child care, workplace flexibility and workplace parental leave policies to meet the needs of a workforce in which women held half of the jobs prior to the pandemic.”

The child care crunch hits new parents particularly hard, because few day care centers accept infants younger than 6 weeks. Infant care is staggeringly expensive. Wisconsin ranks 20th among states and the District of Columbia for most expensive infant care — with an average annual cost of nearly $12,600, according to the Economic Policy Institute. A minimum wage worker in Wisconsin would need to work full time for almost a year to pay that bill alone.

But, as Jones said, “When a child arrives, someone has to take care of it.”

Offering a parent six, eight or 12 weeks of leave following a birth may seem small, Jones said, but the implications “can reverberate throughout the rest of her working life.”

Without paid leave, women are more likely to leave the workforce for longer periods — even years — after giving birth, Jones found. That means lost wages and lower future earnings. The median working woman loses more than $250,000 in wages after staying home for six prime working years. That’s on top of foregone wage increases over the rest of her career.

Career left behind

Amy’s life might have looked different had she taken more time off after delivering twin boys in August 2020. She worked as a Madison-based behavior analyst for kids with autism. She requested that her last name be withheld to protect her family’s privacy and avoid drawing attention to her former employer.

Twins run in Amy’s family, so she wasn’t shocked to see them on an ultrasound. But disbelief struck when she went into labor 10 weeks early.

Although generally healthy, each of the twins weighed less than 4 pounds at birth and couldn’t breathe or eat on their own. Amy had up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave through the federal Family and Medical Leave Act. That meant paying her company while away to continue her health insurance, which required monthly contributions. A relatively new employee, she didn’t qualify for their short-term disability plan.

Amy took just three weeks of leave, returning to remote work even before the twins finished a 45-day stint in the neonatal intensive care unit.

“I’d take my computer to the NICU and just kind of do what I need to do,” she said.

She constantly checked her work email alongside the twins, saving the rest of her unpaid leave for when the hospital cleared them to go home.

“It just felt like I had to push past any physical or mental pain and just field it because that’s what I had to do,” she said.

The twins are now thriving at 17 months old. But Amy laments missing out on crucial moments while working full time.

“In the morning it’s like: up, fed, dressed, out the door, drop them off,” she said. “And at night, it’s like fed, bath, bed. I don’t play with them.”

The result: Just before last Christmas, Amy quit her job in a field that’s short of workers. She’s now staying home with her sons and nannying another child for extra income. The family will roughly break even by avoiding child care costs.

“It’s been a really big decision, because I’ve worked really hard,” she said. “I have a master’s degree and passed the board exams.”

Paid leave’s health benefits

Paid leave policies deliver additional benefits to public health — including strengthening early child-parent bonds, research shows.

That bond reduces infant mortality, improves brain development and increases timely vaccinations. It also lowers the chances of postpartum depression and anxiety among parents.

Choosing day care doesn’t inherently harm a baby, but stress — whether related to the separation or worries about the quality or cost of care — can hinder their development, said Julie Poehlmann-Tynan, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of human development and family studies.

“Babies are often really sensitive to what’s going on,” she said.

Since babies require high-quality, lower-stress care, Poehlmann-Tynan said, policymakers should consider how best to support a child’s transition to family life.

Waunakee cosmetologist Leah Cummings said she constantly worried about finances while on unpaid leave after delivering each of her three daughters, sometimes scouring the house for loose change.

“It definitely causes some level of depression when you have to worry so much about money just to make ends meet,” she said. “It’s draining and exhausting and it takes away the joy and the happiest time of your life.”

An impossible balance

That was the case for Megan Diaz-Ricks, who returned to work completely heartbroken eight weeks after delivering her second son in August.

As an executive at the Madison-based nonprofit Common Wealth Development, Diaz-Ricks lacked paid family leave benefits. Under different circumstances, she could have tapped paid sick and vacation days, but she burned through most of those while grieving her mother’s death in 2019.

She took six weeks off at two-thirds of her pay under a short-term disability plan she paid into and was not paid during her final two weeks away.

“It was really hard for me to feel the stress of the financial weight of ‘How are we going to pay our bills?’” she said. “And also, how am I going to spend as much time with my son as possible?”

While pregnant with her first son in 2018, Käri Rongstad, who teaches ninth grade English at Madison’s Memorial High School, was surprised to learn she lacked paid family leave benefits — particularly in a field composed primarily of women who teach children. She delivered a second son in December and is now at home — using roughly five weeks of accrued paid sick time and taking an additional 10 weeks of unpaid leave.

The five-week cushion seemed precariously thin, especially during the pandemic. Rongstad worried about the coronavirus every day in the classroom; even if it didn’t harm her or the child, exposure could trigger a quarantine that would drain her sick days even before she delivered her son. The Madison School Board approved a paid COVID-19 sick leave policy for teachers and staff in mid-January, but only after Rongstad delivered her son.

“Teaching is a really stressful profession, especially now,” she said. “Being a parent and being a teacher, there’s a balance that seems impossible to kind of find.”

Inaction on popular policy

The House-approved version of Biden’s Build Back Better Act would mandate and fund four weeks of paid family leave. It would apply to nearly every U.S. worker, including the self-employed.

But the bill — which would also cap child care costs for working families, among many other provisions unrelated to parenting — has been declared dead in the Senate. Democrats narrowly control the chamber, but Sen. Joe Manchin, D-West Virginia, has voiced opposition to the bill alongside Republicans.

The inaction persists despite the popularity of paid family leave. Some 84 percent of Americans backed such a mandate in 2019, according to a CNBC survey.

Wisconsin legislation has gained even less traction.

In 2019, Rep. Sondy Pope, D-Mount Horeb, and Sen. Janis Ringhand, D-Evansville, introduced bills to establish a paid family and medical leave insurance program for Wisconsinites. Like a health insurance or retirement plan, employees who opt in could contribute to a trust fund and draw untaxed funds during leave.

Sara Finger, founder and executive director of the Wisconsin Alliance for Women’s Health, who helped draft the bills, said the proposal “is really about an employee contribution,” taking pressure off of employers.

Neither bill received a hearing in the GOP-controlled committees that received them. Finger and her colleagues are weighing a fresh proposal while monitoring negotiations in Washington.

“The demand continues to grow as Wisconsinites and Americans all over are realizing the impossible situation we’ve been put in prior to the pandemic — and even more so during the pandemic,” Finger said. “We can no longer treat these issues as partisan.”

Employers see benefit

And when employers pay for family leave? It can yield benefits. California made paid leave available to workers through a payroll deduction beginning in 2004. In a 2010 survey, 87 percent of businesses reported no increased costs, and 9 percent reported cost savings through reduced turnover.

A 2016 study of Rhode Island’s similar program “found little evidence of significant impacts of the law on employers.”

Missy Hughes, secretary and CEO of the Wisconsin Economic Development Corp., said Wisconsin’s workplaces increasingly find paid leave a sound investment.

“Employers who are making smart moves to support their families — whether it’s offering on-site child care, or child care benefits or paid leave — those employers are saying to me, ‘Missy, I wish we had done this sooner,’” she said.

Leah De Gabriel said a paid parental leave policy solidified her commitment to work at Madison-based Hy Cite Enterprises, which manufactures household products.

The mother of two used unpaid leave after delivering her first daughter, but the company instituted a paid leave policy before she delivered her second daughter, making the experience far less stressful, De Gabriel said.

“It was one of the things that I knew made me want to stay at the company, just knowing that it was one of the benefits — and they did it because they wanted to,” she said.

That tracks with experiences at other companies, Hughes said, where family-friendly policies improve productivity and loyalty.

Finger said workers should expect employers and government to accommodate families.

“It doesn’t have to be this way,” she said. “We are such an outlier in the world. And if the pandemic again hasn’t elevated this issue to a level of absolute priority, I don’t know what will.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated on Feb. 1, 2022 to clarify details related to the Clark family’s relationship with their son’s early child care provider.

This story was edited by Wisconsin Watch Deputy Managing Editor Jim Malewitz. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (wisconsinwatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.