In the 15 months since Rowan Wilson first contracted COVID-19, he’s been playing a kind of Whack-a-Mole with symptoms.

“Every time I would sort of get one new symptom under control, another thing would come up,” he said. “And I would be like, ‘What is this, this is awful, I can’t handle this’ — and it would just take over my life.”

The symptoms have ranged from the more typical, like extreme fatigue, to the strange, like a full-body itch that won’t stop.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“It’s so random, I feel like — I’m just complaining about literally itches,” he said. “But when it becomes that serious, it just takes over your life, and you can’t think about anything else.”

Wisconsin Public Radio first learned of Rowan’s struggles with the disease through WHYsconsin.

Rowan, who is 17, has long COVID, a chronic illness that develops in some people who contract the coronavirus and leads to long-term symptoms. Because the disease is still so new, long COVID isn’t well understood — particularly among children. A review of several studies of long COVID in kids found its prevalence ranged from 4 to 66 percent, using different criteria for what the disease looked like. People at higher risk of developing long COVID include people who are older, female, have allergic diseases and pre-existing mental or physical health concerns.

For Rowan, who lives in Watertown, this means doctors often aren’t much help.

“I can go to the doctors, and they’ll be like, ‘Wow, gee, that’s awful, I wish I could help,’” he said. “And then they charge you $400, so it’s just like, what’s the point, a lot of the time.”

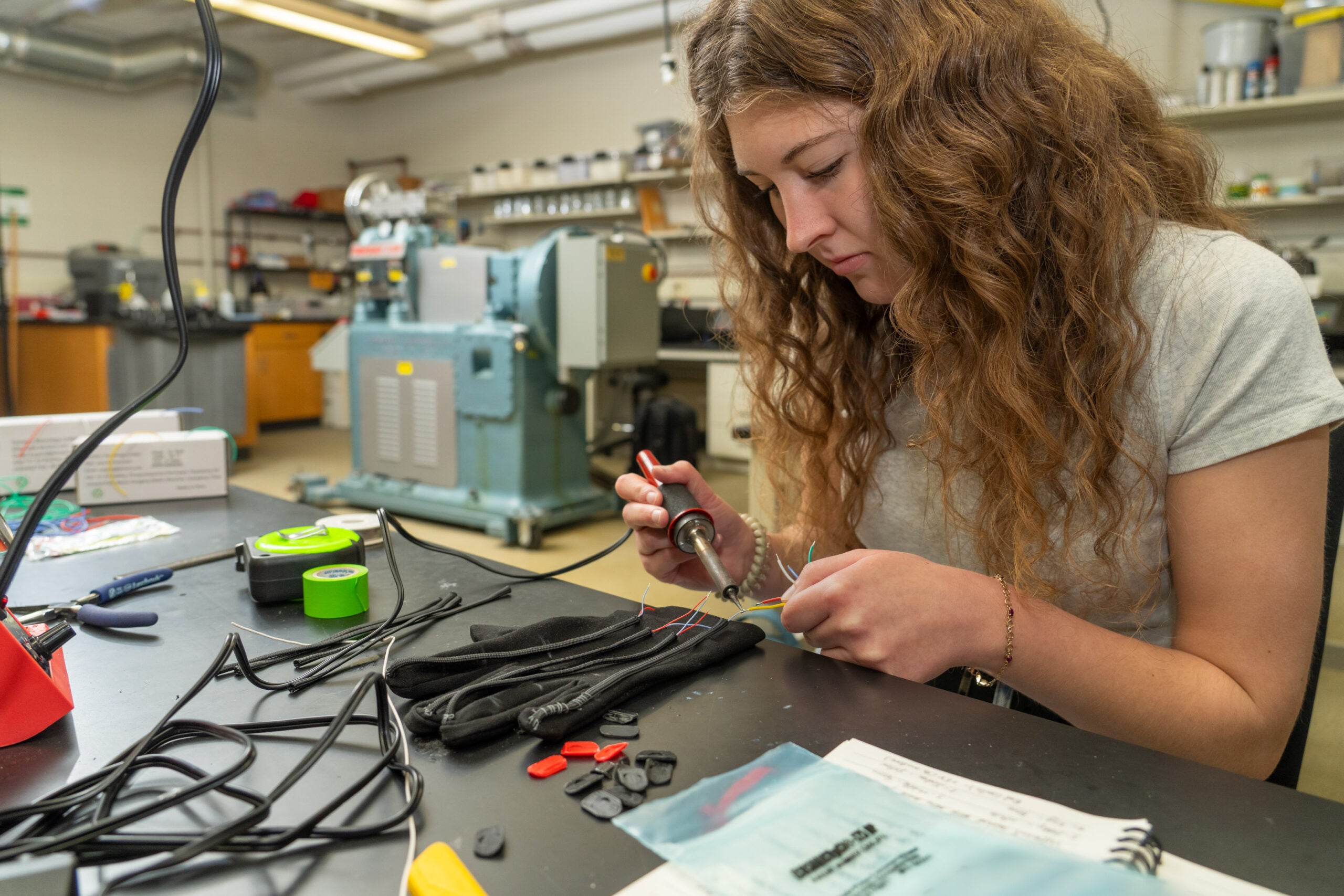

Ava Pennycook, a 17-year-old in Janesville who’s been open about her own struggles with long COVID, first contracted the virus in July 2020. She lost her sense of taste and was light-headed, nauseated and off-balance, but never had a fever or a cough – her doctors tested her several times for mononucleosis before figuring out she had COVID-19.

Since then, there’s been wave after wave of symptoms. She fell down the stairs at school because of dizziness, was having trouble with her memory and consistently has chest pains. Lately, she’s also been having trouble with her joints.

“It was really bad, I don’t know if it was just because it was cold outside, but I was scraping off my car,” she said, “and I got back in my car, and I couldn’t move my thumbs because they hurt so bad.”

In April, Ava was also diagnosed with celiac disease, a digestive and immune disorder, and Addison’s disease, a condition where the adrenal glands don’t produce enough cortisol. Her doctors suspect that the conditions were triggered by COVID-19.

At one point, her cortisol levels were so low they didn’t register on the test.

“I was going to get the (COVID-19) vaccine, and my doctor called and said, ‘Hey, is Ava OK right now?’” she recalled. “I was basically in adrenal shock, so when that happens, you can have seizures or go into a coma or something like that.”

Before she contracted COVID-19, Ava was an all-star cheerleader with a grueling year-round practice schedule to master tumbling, stunting and dance routines for competitions. After her symptoms started, it took months for her to get back to cheering, and even then, she stuck to her high school’s team rather than returning to the competitive circuit. During her first few football games, she cheered for the first quarter but then had to rest on the bench.

Rowan was involved in forensics, music and drama before he got sick, and his mom said he had a perfect school attendance record. Now, it’s common for him to stay home one day every week, or, in better periods, every two weeks, because of overwhelming fatigue or other symptoms. Rowan dreamed of being an actor, but worries that’s out of reach if his symptoms persist. He’s even having to rethink his college plans.

“I’ve always wanted to go to Madison,” he said. “Now I realize, ‘Wow, can I even move out of home?’ Because I don’t know if I could do all that walking across campus, and living on my own and having a job.”

The illness has reshaped both kids’ lives in big and small ways. Their taste hasn’t quite returned to normal — Rowan, for example, can’t eat pickles anymore because they’re too salty. Ava used to love cottage cheese but can no longer stomach it.

Ava used to be terrified of needles and blood draws, and was so bad at swallowing pills that she had to take liquid Tylenol. After so many tests and with a handful of pills to take at strict intervals every day, she’s a pro. Her hard-won knowledge of the body’s functions have given her an unexpected edge in some of her classes.

“When my AP psych teacher is asking, ‘Does anyone know where the adrenal glands are?’ I’m like ‘Oh, they’re in your kidneys,’” she said. “And he’s like ‘How do you know that?’ and I’m like, ‘Oh, well, mine don’t work.’”

She’s a familiar face in the nurse’s office and with her school’s secretarial staff, since she sometimes has to go lie down, or leave school early when she’s not feeling well. Maintaining healthy habits is essential now. She drinks water consistently throughout the day, because dehydration can knock her out pretty quickly. She’s religious about taking her pills on schedule.

When she and her boyfriend drove to Six Flags over the summer, her mom, Amy Pennycook, pulled him aside.

“I was like, ‘Hey, Jack, I have to talk to you about something’ — you should have seen the look on his face,” Amy said. “I was like, she has to have her medicine at this time, you have to make sure she drinks water.”

Ava said her friends and teachers are understanding, though it’s hard for her to explain why she’s not feeling well, or what’s happening, since so little is known about long COVID.

Rowan said he has a lot of friends who are chronically ill or living with disabilities, so while they may not understand his particular illness, they’ve dealt with a lot of the same symptoms and trade tips.

“They understand what it’s like to just not have any clue what’s going on or how to fix it,” he said.

Rowan set up accommodations through his school that give him more time to complete tests and a longer period after missing a day of school to turn in assignments.

He’s also shifted from barely spending time online to making it a huge part of his social life.

“There’s really not much of a choice, I’m on Discord like 90 percent of the day, because it’s not like I get to see my friends as often,” he said.

Amy has also found a community online. She’s joined Facebook groups for COVID long-haulers and their families, and, since Ava’s later diagnoses, groups for Addison’s and celiac diseases. She said she’s been seeing more and more new members of the Addison’s group who also contracted the illness after having COVID-19. For her, it helps to see other people trying to figure out a complicated set of symptoms, and to know her family is not alone in grappling with the illness.

The family has also had a lot of people reach out directly since the Janesville Gazette did a series of articles about Ava.

“It’s been nice being able to talk to moms that have teenagers,” Amy said. “That’s why we agree to talk to people and put the story out there, just because we hope it will help somebody else, and help people trying to figure out the virus and how it affects people long-term.”

Though long-haulers often find each other, Rowan said it can be frustrating that other people seem to think of the consequences of COVID-19 only in terms of deaths, without remembering that living through the aftereffects of the virus can be devastating, as well.

“We seem like the forgotten people, because nobody really cares,” he said.