Sitting in his North Side Milwaukee rental house, Nazir Al-Mujaahid spoke matter-of-factly about the challenges his son Shu’aib faces, while the quiet 9-year-old lingered in another room. Shu’aib excels at sports, Al-Mujaahid said, but his speaking skills developed late, and he still lags behind his 6-year-old brother in reading.

Al-Mujaahid, 45, believes that lead poisoning is hindering his son’s development. Confirming precisely where the lead came from is impossible, but Al-Mujaahid suspects the aging lead pipelines that carried drinking water into his home.

The city for years failed to warn the family of potential lead hazards in their home — or that Shu’aib registered elevated lead levels as a toddler in 2014, Al-Mujaahid said. Three years later, the family stopped drinking from their tap after learning about risks from lead pipes.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“My awareness of it hasn’t been an issue taken seriously at all. It’s got some media attention, but it’s a joke here,” Al-Mujaahid said. “I found out about it because my son wasn’t developing normally.”

Shu’aib is among 9,600 Wisconsin children younger than 16 found to be poisoned by lead between 2018 and 2020, according to Wisconsin Department of Health Services data. The neurotoxin damages the brain and nervous system, particularly in young children, sometimes causing learning and behavioral problems and stunted growth.

Nearly two-thirds of Wisconsin’s lead-poisoned children live in Milwaukee County, where 5.6 percent of children tested in 2020 had blood lead levels above 5 micrograms per deciliter, the level that the state defines as poisoning. That’s compared to 3.4 percent of children statewide. Wisconsin saw 23 percent fewer children tested for lead between 2019 and 2020 as the pandemic kept many families out of clinics for check-ups.

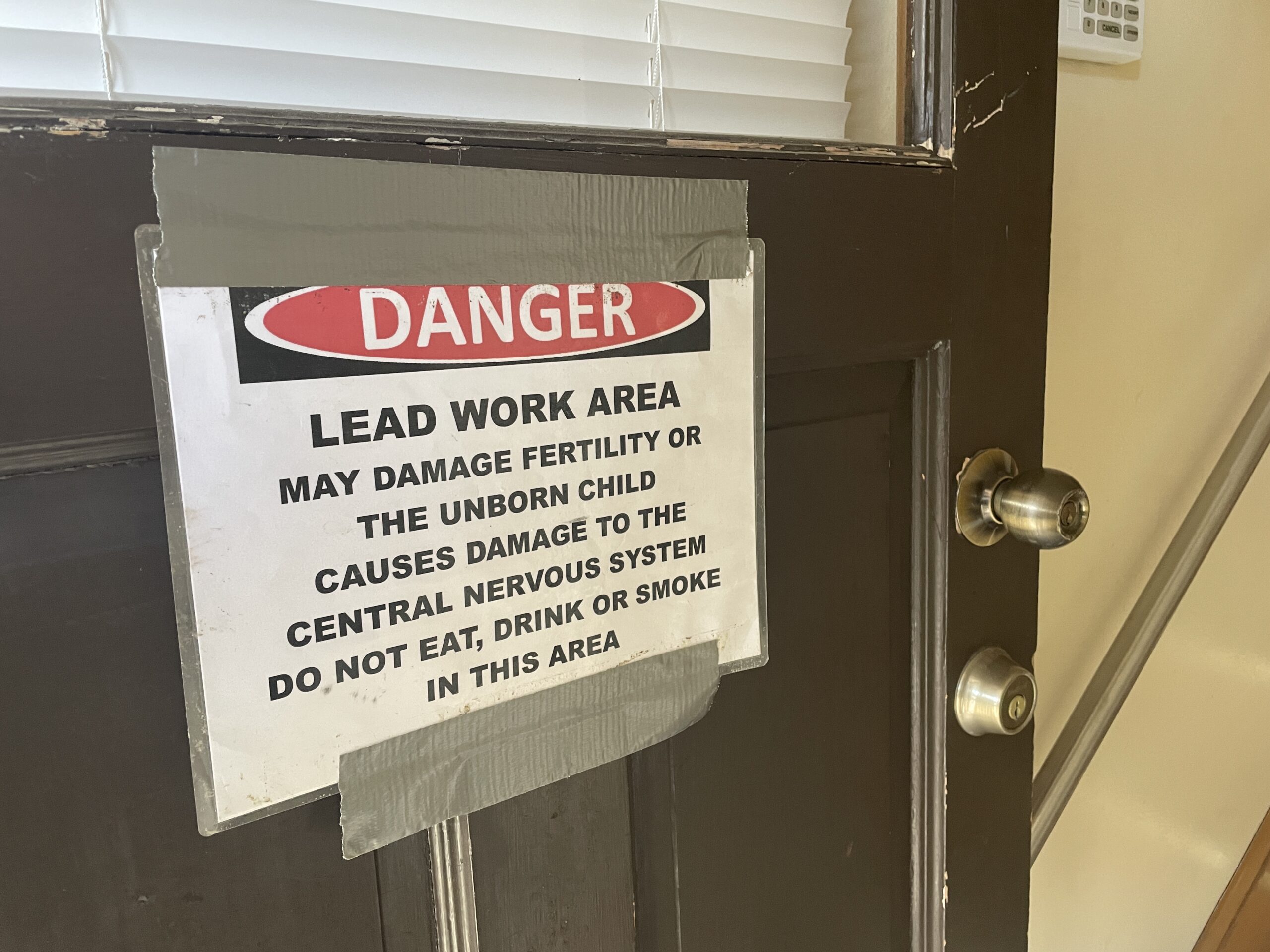

Children can become lead poisoned by ingesting paint, lead-tainted water, soil, dust or other lead-based products. Some 90 percent of Wisconsin’s lead-poisoned children live in homes built before 1950, according to DHS. Those homes are more likely to have lead-based paint and lead plumbing.

Gov. Tony Evers and Milwaukee Mayor Tom Barrett have called for more aggressive lead service line replacements, but their own health departments primarily focus on addressing lead paint and dust, calling that the predominant hazard, as do many experts and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Since 2016, when the Flint, Michigan water crisis was declared a disaster, Wisconsin has replaced about 20 percent of known service lines made of lead and galvanized steel that might contain lead flake buildup — or other materials that might contain lead, according to a Wisconsin Watch analysis of state Public Service Commission data.

Despite that, Wisconsin doesn’t require local governments to test drinking water during home lead hazard investigations, even though it can make up 20 percent of a person’s total exposure to lead, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency — or up to 60 percent for infants consuming mostly mixed formula

Activist Says Problem Is ‘Public Health Crisis’

Childhood lead poisoning rates in Milwaukee and statewide have steadily decreased in recent decades — in line with national trends since lead was phased out in paint and gasoline. Yet Milwaukee in 2020 still had a higher percentage of lead-poisoned children than Flint did in 2015 after state officials approved a drinking water switch without treating for corrosion — causing lead to leach into drinking water.

Al-Mujaahid is among residents urging Milwaukee officials to bolster lead poisoning prevention efforts — including by investigating risks from lead in drinking water and accelerating replacements of lead service lines.

Calls to focus on drinking water hazards come as the Milwaukee Health Department seeks to rebuild trust in the three years since Barrett announced that the department failed to track whether it alerted thousands of families that tests detected lead poisoning in their children. The city is awaiting the conclusion of a criminal investigation that local news reports have linked to the health department’s response to childhood lead poisoning. First-year Milwaukee Health Commissioner Kirsten Johnson has called lead poisoning the city’s “pandemic before the (COVID-19) pandemic” and her top priority to tackle.

Some other major Wisconsin cities — notably Madison and Green Bay — have replaced all of their lead pipelines. But Milwaukee is much larger and installed exponentially more lead service lines than others. Although most communities were moving away from lead service lines by the 1920s, Milwaukee stuck with lead for longer amid lead industry lobbying — mandating their use until 1948 and waiting until 1962 to ban them.

Wisconsin communities have replaced more than 115,000 utility-owned and privately-owned service line portions since 2016, when the state launched a grant program to help utilities finance upgrades that can cost thousands of dollars per pipeline, a Wisconsin Watch analysis shows. Still lurking in 2020 however: an estimated 465,000 pipeline portions made of lead or other potentially hazardous materials. (Most service lines consist of a utility-owned portion and a privately-owned portion.)

Milwaukee has replaced less than 1,000 of its full lead service lines annually since launching its effort in 2017. Replacing the remaining 70,000 lead pipes at that pace would take more than 70 years, and the full price tag would cost hundreds of millions of dollars that city officials say they lack.

Wisconsin’s Republican-controlled Legislature has rejected Democratic Gov. Tony Evers’ years-long push to boost funding for pipeline replacements statewide, with some Republicans saying too much money would flow to Milwaukee. Federal funding may provide the most hope, including pandemic stimulus dollars that could pay for pipelines and President Joe Biden’s infrastructure bill, a version of which the U.S. Senate approved this month.

But some residents are tired of waiting, saying that Milwaukee should make pipeline removal a higher priority.

“It’s a public health crisis,” said Derek Beyer, a steering committee member of Get The Lead Out, a coalition of Milwaukee groups fighting for speedier replacements. “It’s not an option to wait 30 more years or whatever, to beg for some money that might not ever come.”

Milwaukee Family Not Notified

The Al-Mujaahid family has rented a house in the predominantly Black Roosevelt Grove neighborhood since 2014. The home has lead service lines, city records show, but Al-Mujaahid knew little of such hazards until a few years later. And in 2017, a fingerstick test detected 11.4 micrograms per deciliter of lead in Shu’aib’s blood, prompting the Milwaukee Health Department to warn the family in a letter that “Lead poisoning is a serious illness which can cause behavior and learning problems.”

The test came as Shu’aib, then 4 years old, was developing his speaking skills more slowly than his peers, Al-Mujaahid said, adding that he was more introverted than other children. The family initially suspected autism.

Along with the warning letter, the health department sent fliers on how to reduce children’s exposure to lead and apply for funding to replace windows or to remove other home lead hazards.

It wasn’t the first time that Shu’aib tested positive for lead poisoning. A 2014 test had flagged 6.4 micrograms per deciliter in Shu’aib’s blood. No immediate follow up tests were scheduled, records show, and Al-Mujaahid said he wasn’t notified of the high level. The health department could not confirm whether its current notification policy for test results of at least 5 micrograms per deciliter was in place at the time, spokesperson Emily Tau told Wisconsin Watch.

“We didn’t really get anything until years later. So we weren’t even aware that we should have been very concerned,” Al-Mujaahid said.

Milwaukee Water Works tested the home’s drinking water after Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service profiled the family’s lead saga in 2018. Three samples showed lead levels ranging from 0.35 to 2.5 parts per billion (ppb), records show. That’s far below the EPA’s long-unchanged 15 ppb “action level” — the trigger for public water systems to take actions such as pipeline replacement and education.

But many expertscall the federal threshold far too high, considering that no level of lead exposure is considered safe. Biden’s EPA has delayed and is reviewing Trump administration rule revisions that would leave the action level in place.

The Al-Mujaahids turned away from tap water after learning about the lead pipelines in their home. For drinking and cooking, they use 5-gallon jugs of store-bought water. And the family wonders whether lead-tainted water flowed through their previous North Side Milwaukee rental home, where they lived when Shu’aib was first tested. That house also has lead service lines, city records show.

City Department Faces Scrutiny

The family’s experience wasn’t unique. In January 2018, Barrett announced that his office identified “mismanagement and significant shortfalls” in how the Milwaukee Health Department followed up with families about elevated lead levels in children. Mainly, the department lost track of whether it had followed up with 8,000 families over three years whose children registered elevated lead blood levels.

A 2020 Public Health Foundation audit found the department made progress in fixing the lead poisoning program, but it failed to resolve all shortcomings identified before 2018. Among the lingering issues: “inefficient and ineffective” documentation and surveillance systems for blood testing, slow and potentially incomplete risk assessments of lead exposure, long waits for lead-safe housing for children with elevated lead blood levels and a lack of accountability in budgeting. The department last month acknowledged that it failed to follow up with a family of multiple lead-poisoned children, and it is planning a fresh audit.

“Overcoming these challenges and rectifying any mishandlings of cases is a tremendous task that will take time,” Tyler Weber, Milwaukee Deputy Commissioner of Environmental Health, told Wisconsin Watch in a statement, adding that his team is “dedicated to urgently achieving” that goal.

City Effort Was Prioritizing Paint

Barrett, Evers and the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources have for years publicly backed the idea of aggressive pipeline removal — pending available funding, calling lead-tainted water a significant threat. But health officials continue to prioritize paint over drinking water when investigating lead hazards in homes.

“The Milwaukee Health Department’s focus is on lead abatement in paint and soil, as lead-based paint hazards are the primary source of lead exposure in the Milwaukee community,” Weber said. “However, we know lead poisoning can also occur from contaminated drinking water, so the Milwaukee Health Department distributes free water filters to anyone in the city of Milwaukee who needs them to eradicate the danger until Milwaukee Water Works is able to replace the service line to the home.”

A spokesperson for the Wisconsin Department of Health Services, which contracts with local health departments to follow up with families after positive tests for lead poisoning, downplayed drinking water hazards in an email to Wisconsin Watch.

“Water is not an issue in Wisconsin the way paint is when it comes to lead poisoning,” spokesperson Elizabeth Goodsitt wrote.

That contrasts with other Evers administration messaging. Evers since 2019 has unsuccessfully pushed the Legislature to approve $40 million for additional lead service line replacements, and his DNR chief, Preston Cole, said in July: “We know aging water pipes can leach lead into the drinking water causing serious health problems, especially for infants and children.”

Wisconsin local health departments in 2019 identified lead-based paint as a hazard in 97 percent of investigations of elevated blood levels, Goodsitt noted, and they flagged other primary hazards just 3 percent of the time. The disparity widened in 2020, with investigations implicating paint 99 percent of the time.

But local health departments investigate only a fraction of lead poisoning cases in Wisconsin, and they rarely test drinking water — meaning that most drinking water hazards would not be reflected in such data.

The state mandates investigations and case management services for children only when one venous blood test detects at least 20 micrograms per deciliter of lead — or if two tests conducted at least 90 days apart find lead at 15 micrograms per deciliter. That’s far above the 5-microgram threshold that the state defines as poisoning.

“The blood lead level at which a (local health department) intervenes is dependent on their caseload and resources,” Goodsitt told Wisconsin Watch.

Water Testing Not Required

“Health departments are not required to test water as a part of their lead hazard investigation and it is uncommon to have water samples collected during an investigation,” DHS told Wisconsin Watch in an email from another spokesperson, Jennifer Miller. “Instead, if there is any question about the water we always suggest installing filters at the point of use, or the family use a different known safe source of water (bottled).”

Investigators sometimes test water from private wells, DHS added.

Milwaukee offers — and strongly encourages — drinking water testing for families during elevated blood level investigations, but doing so requires consent from all tenants of a building, Tau said in an email. Water must stay stagnant in service lines for at least eight hours. “This poses an additional challenge for homes that are multi-family homes, duplexes, triplexes, etc. and some tenants choose to opt out of the water testing for that reason,” Tau said.

Henry Anderson, a University of Wisconsin-Madison professor of population health and expert on environmental and occupational diseases, said prioritizing paint hazards made sense — particularly for protecting toddlers who can cruise around a house.

“There’s so much more lead in a paint chip than there is in a glass of water,” said Anderson, Wisconsin’s former state chief medical officer. “When there’s an old house, it has paint chipping off the walls, they are crawling around, putting their hands in their mouth — and hands are sticky. And so ingestion of paint chips remains important.”

But Marc Edwards, a Virginia Tech University engineering professor who helped expose Flint’s water blunder, is among experts who contend that governments dangerously downplay drinking water’s role in lead poisoning by focusing on paint. Edwards said governments face a “massive conflict of interest” in parsing dangers from paint from those in drinking water, because governments often own the pipes — and benefit from lawsuits accusing paint companies of damaging public health by distributing lead-based products.

If governments don’t own the pipelines, mandates may have put lead in the ground, as in Milwaukee.

“If it’s true lead paint is a danger, then lead in water is a danger, too,” Edwards said. “Anyone who says it’s 90 percent lead paint is being overly simplistic at best and deceitful at its worst.”

Paying For Replacements

Al-Mujaahid wants his home’s lead service line replaced, but a question looms: Who would pay? Homeowners in Milwaukee and most Wisconsin municipalities own the portion of service lines from the curb stop to the home. Municipalities are responsible for only the portion between the curb stop and water main. State law bars municipal workers from performing private construction projects, and partial service line replacements can worsen lead exposure.

A 2017 Wisconsin law allows utilities to subsidize private-side replacements. Grants provided by a utility can’t eclipse more than half of the replacement cost of the private service line side, but utilities may also provide loans, and some piece together state and federal grants.

Milwaukee in recent years mandated replacements for lead pipes found to be disrupted or leaking — and those that serve private schools and child care providers. For mandated replacements, a city cost-sharing program limits the tab for participating property owners to $1,843. Properties with more than four units are not eligible for cost sharing for required replacements. Also ineligible for the subsidy: Milwaukee property owners who choose to replace service lines when not required. They must pay 100 percent of the bill.

Al-Mujaahid said his landlord has no interest in paying for a new pipeline, and Al-Mujaahid doesn’t want to pay for work on a property that he doesn’t own. The city should bear full responsibility for the lead pipelines it mandated decades ago, he said. “It’s their responsibility, not mine.”

Since 2017, Milwaukee’s utility says it has swapped out 3,881 pipelines. Advocates want more urgency to replace the remaining 70,000.

“There’s no excuse at this point for the situation we find ourselves in today. It’s criminal,” said Robert Miranda, a spokesperson for the Milwaukee-based Freshwater for Life Action Coalition. “What is happening in Milwaukee is a crime against humanity, is a crime against our public health, and people need to be held accountable.”

But Karen Dettmer, Milwaukee Water Works superintendent, sees “good progress” in replacements and called Milwaukee’s drinking water program “one of the best in the nation.” She cited the utility’s compliance with EPA’s embattled Lead and Copper Rule since the 1990s, when it began running corrosion control chemicals through its pipes. Still, Dettmer said she understands calls to pick up the pace on replacements.

“The overwhelming interest of the elected officials in the city of Milwaukee would be to replace the lead service lines as quickly as possible,” Dettmer told Wisconsin Watch. “But at the same time, they share my concerns about the cost to the ratepayers and the cost to property owners.”

Full Replacement Costs $800M

Replacing public and private portions of every Milwaukee lead service line would cost about $800 million, the city estimates. That’s the equivalent of more than half of the city’s entire 2021 budget, which includes $4 million in pipeline aid to property owners to replace 1,100 lead service lines.

Barrett has suggested earmarking tens of millions of pandemic stimulus funds for fixing lead paint hazards, and he’s waiting to see whether Biden’s infrastructure bill will deliver additional funding for pipeline replacement. That could determine how the city prioritizes its federal dollars, he said in May.

The $1 trillion U.S. Senate-approved version of Biden’s proposal includes $15 billion for pipeline replacements nationwide. The bill faces an uncertain future in the House, where Democrats in the majority are pushing for a bigger bill. Biden originally proposed $45 billion for pipelines.

But funding alone may not eliminate all obstacles for overhauling Milwaukee’s pipeline system. Eying an aging workforce and challenges of finding qualified replacement workers amid a labor shortage, Dettmer says retaining enough employees to significantly speed up service line replacements won’t be easy.

“We have a number of retirements that have come in the past few years,” she said, adding that the city is pushing for workforce development resources. “We have retirees that we watch very closely that are coming to their 35 years of service at the city, and we anticipate that they will take advantage of that retirement opportunity.”

Lead-Free Pipes In Some Cities

Some Wisconsin cities have already replaced all of their lead pipelines. Madison was the nation’s first utility to do so — a $19.4 million project that took a decade to complete beginning in 2001. The city originally had 8,000 lead service lines, a fraction of Milwaukee’s inventory, and homeowners paid about 20 percent of the cost. Madison launched the effort after violating EPA lead standards and deciding that the alternative solution — running orthophosphate, an anti-corrosive, through the pipes — would pollute Madison’s lakes, worsening algae blooms.

Green Bay joined Madison’s lead-free ranks last October when it finished a five-year effort to replace all 1,782 utility-owned and 247 privately-owned lead lines. The price tag: $6.2 million for public-side replacements and $1.2 million on the private side. Water rate increases, federal grants and state grants funded the project. To initiate a pipeline replacement, homeowners contacted a private contractor and applied to the utility to cover the full cost.

“I’ve worked on committees and national committees, too, where you could probably never cost-justify a total lead service replacement program over maybe putting chemicals in,” said Nancy Quirk, Green Bay Water Utility general manager. “But we felt very strongly that we wanted to get rid of the source of the lead, that we did not want to put additional phosphorus loadings into the Fox River — that were already having dead zones and cyanotoxins growing.”

Some property owners initially resisted, seeking to avoid the disruption of pipeline work, Quirk said. But the city eventually required all property owners to work with the utility to swap out any lead pipelines, threatening to fine those who did not comply. Green Bay also faced challenges mapping which pipelines contained lead and keeping workers safe during the pandemic, Quirk added.

Spurred by Flint’s water crisis, Eau Claire has replaced hundreds of its 1,266 lead service lines since 2017 and has a goal to finish by 2023. A city ordinance requires the replacement of lead lines when they are encountered, and residents of older neighborhoods — especially those built before the 1940s — can apply for a replacement. DNR funding allows the utility, which is canvassing neighborhoods to promote the program, to directly pay contractors up to $2,600 per service line, leaving any additional cost to homeowners. Lane Berg, utilities manager for the city, said homeowners typically bear no cost.

“The biggest thing I see on the program — the improvement — is when the city started reimbursing the contractor directly,” Montana Birt of Montana and Son Grading told Wisconsin Watch during a pipeline replacement in Eau Claire. “That way it takes all the burden off of the homeowner.”

But in Milwaukee, Al-Mujaahid has lost faith that his home’s lead pipeline will be removed. The family is contemplating leaving — to protect the health of their children and to escape a starkly segregated city that’s among the most difficult places in the country for African-American residents to succeed, according to some studies.

“My thing is to just get up out of here,” he said. “Minimally somewhere without these lead lines. Ideally out of this country.”

Editor’s note: Diana Butsko was an Edmund S. Muskie reporting fellow for Wisconsin Watch. She is studying at Southern Illinois University through a Fulbright scholarship. Madeline Fuerstenberg of Wisconsin Watch contributed reporting. The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (wisconsinwatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.