When David Phillips of Iron River was expecting his first child last year, he combined all his vacation and sick time to take paternity leave from his job as a corrections officer at the Douglas County Jail.

When he returned to work, he was immediately hit with having to work a lot of overtime.

“And that’s not really conducive for a family life, with especially a newborn,” said David.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

His wife Shannan said it was almost like he was punished for spending that time with their daughter Lillian.

“He was (the) lowest man on the totem pole,” said Shannan.

Shannan said David would be ordered to work 16-hour shifts because someone called in sick or had symptoms of COVID-19. The situation proved difficult for the young couple as they tried to balance parenting with David’s unpredictable work schedule.

[[{“fid”:”1624136″,”view_mode”:”full_width”,”fields”:{“alt”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”,”title”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width media-wysiwyg-align-center”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:”center”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EDavid%20Phillips%2C%20pictured%20with%20his%20wife%20Shannan%2C%20gives%20his%201-year-old%20daughter%20Lillian%20a%20bottle.%20Phillips%20left%20his%20job%20as%20a%20corrections%20officer%20at%20the%20Douglas%20County%20Jail%20in%20February%202021.%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3EDanielle%20Kaeding%2FWPR%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“alt”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”,”title”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width media-wysiwyg-align-center”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:”center”,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EDavid%20Phillips%2C%20pictured%20with%20his%20wife%20Shannan%2C%20gives%20his%201-year-old%20daughter%20Lillian%20a%20bottle.%20Phillips%20left%20his%20job%20as%20a%20corrections%20officer%20at%20the%20Douglas%20County%20Jail%20in%20February%202021.%26nbsp%3B%3Cem%3EDanielle%20Kaeding%2FWPR%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”,”title”:”David Phillips gives his daughter Lillian a bottle”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width media-wysiwyg-align-center”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]

After three years working 60-plus hours each week, David decided to quit in February.

And he’s not alone. County jails and prisons across Wisconsin have been dealing with staffing shortages due to exhausting work conditions and low pay. The coronavirus pandemic and a nationwide labor shortage have only made things worse.

The staff shortage is not only overwhelming workers, it’s also impacting people housed in correctional facilities statewide.

Jail administrators, former staff, inmates and the state’s top corrections official say it’s not uncommon for staff to be ordered to work double shifts. As of the end of October, the Douglas County Jail had lost 26 of 34 jailers since January of last year.

“Burnout is real,” said Stacey Minter, the county’s lieutenant of jail operations. “They’re trying to avoid the overtime.”

Many former officers like David have gotten jobs in other fields that can pay just as much or more without the stress or risks to their health and safety. Jails and prisons have faced some of the highest risk of exposure to COVID-19. In October, the Douglas County Board approved a 5 percent pay increase for jailers and sergeants to help with retaining staff.

Recruitment and retention has always been difficult in corrections due to grueling work conditions and lower pay, according to Jirs Meuris, assistant professor of management and human resources at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“You have a job that’s already difficult to get people to apply to, to join and then to retain those people. And then you add a labor shortage, as well as a pandemic, that’s going to make that job even harder to do,” said Meuris.

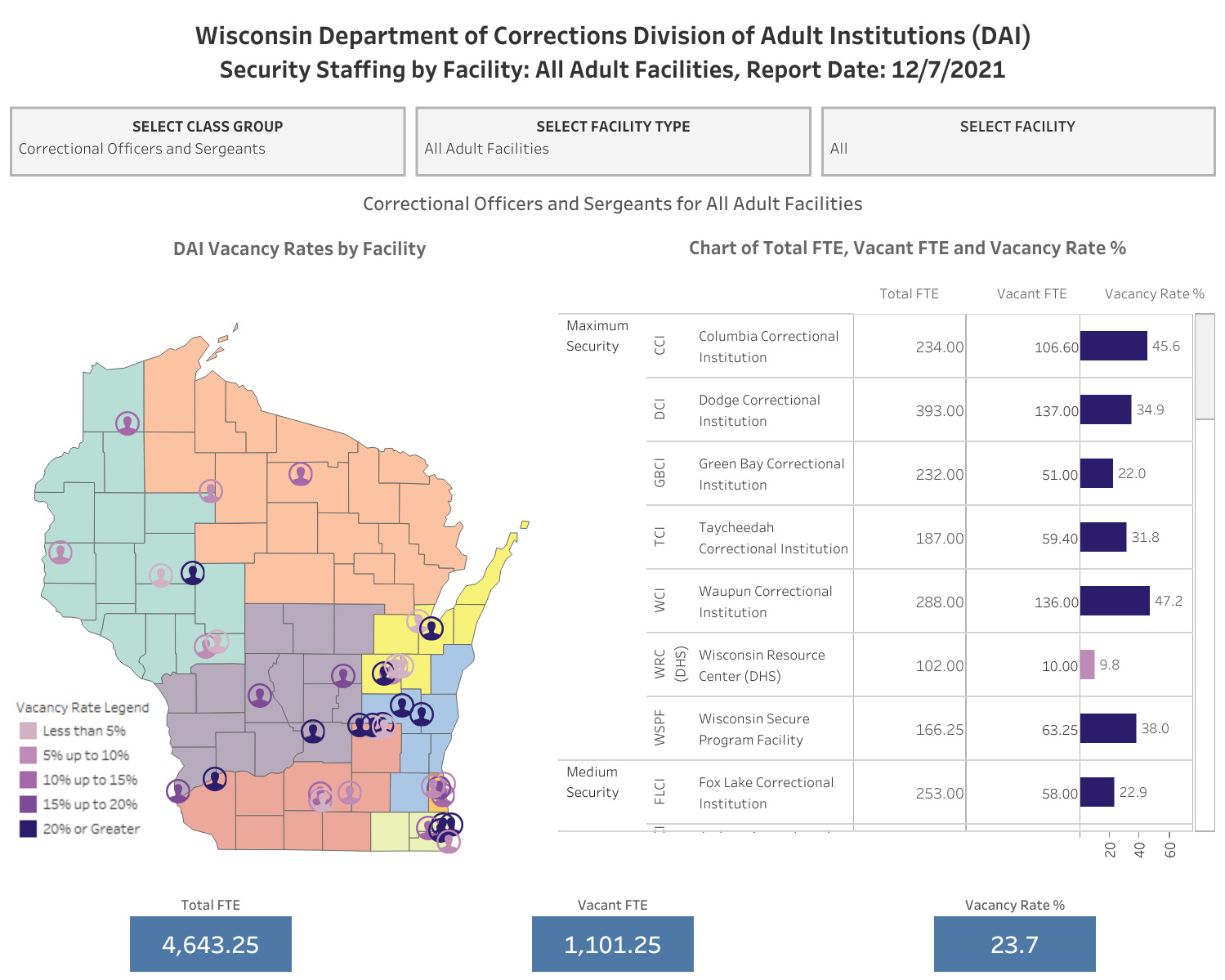

Earlier this year, roughly 15 percent of corrections officer positions were unfilled at Wisconsin’s prisons, according to data from the Wisconsin Department of Corrections. Now, nearly 24 percent or roughly 1,100 jobs remain open. Some maximum-security facilities have close to half the staff they should at prisons in Portage and Waupun.

Corrections officials closed a cell hall at Waupun last year due to staffing shortages. Now, DOC Secretary Kevin Carr said they’re sending almost two dozen officers each pay period to the maximum-security prison from other facilities with more staff. The agency plans to provide additional staffing to Waupun for another six months starting in January and will begin sending officers to the prison in Portage as well.

While staffing has gotten worse, Carr said keeping and finding officers has always been a problem.

“Why would you want to come work for the Department of Corrections at a starting wage below what you can get at the local Walmart or Kwik Trip and be exposed to working in a dangerous environment, long hours with lots of overtime and a lower quality of life?” said Carr.

Lawmakers approved a pay bump for corrections officers from $16.65 per hour to $19.03 per hour under the last two-year state budget to address long-standing vacancies. Carr said they’re trying to hire more people and hoping lawmakers will support another pay increase under the next two-year state compensation plan.

The plan proposes two options. One would raise minimum wages by roughly 50 cents per hour on top of an annual 2 percent wage adjustment. The alternative would boost all pay rates by $5 per hour, but it would require lawmakers to approve additional funding. A public hearing on the plan and a companion bill that would increase wages is being held Tuesday.

Some southeastern Wisconsin counties have turned to federal COVID-19 relief under the American Rescue Plan Act, or ARPA, to address staffing shortages. The move has raised questions about the sustainability of pay hikes when the funding runs out as local governments have faced restrictions on raising revenues through property taxes.

Racine County Executive Jonathan Delagrave said they hope to avoid any increased cost to taxpayers after the county board approved using around $7 million in ARPA funding over the next several years to raise wages for county employees, including an average pay increase of $7.50 an hour to $28.96 per hour for corrections officers. The county’s jail had witnessed more than 100 percent turnover in the past two years.

Delagrave said the results were immediate.

“We were able to fill our positions with experienced correctional officers,” said Delagrave.

At least 10 of those officers left the Milwaukee County Jail in search of higher compensation, according to Inspector Aaron Dobson, the jail’s commander. He said Racine County’s wage increase had an adverse impact on jail staffing. In November, the Milwaukee County Board approved using $1.5 million in ARPA funding to pay the jail’s corrections officers an extra $3 per hour under next year’s budget after nearly 100 positions remained open as of mid-November.

“It becomes even more important to retain the officers we have,” said Dobson. “And we’re hoping that that increased pay will help with that.”

For now, the staff shortage means things move slower. Dobson said they may not be able to offer programs for inmates every day. And, people are spending nearly twice as much time in their cells.

Ron Schroeder is being held in the Milwaukee County Jail pending trial on a first-degree reckless homicide charge. As of mid-November, people were being held in their cells for 16 hours a day compared to just 9 hours overnight prior to the shortage, according to Dobson.

“We’re really locked in our cells a lot of the time,” said Schroeder.

Inmates at the prison in Portage also report being confined more to their cells and having fewer in-person visitation days. Jesse James Anderson has been in prison since 2008 and is serving time for gun and drug convictions. He said most inmates are in their cells for 23 hours each day, creating a hostile atmosphere.

“(Corrections officers) often take (their) frustrations out on (the incarcerated) person. And to retaliate on (their) coworker, they in turn call in ‘sick’ and further this perpetual motion,” wrote Anderson in an email.

State and county corrections officials say they just don’t have enough staff to watch inmates when they’re outside their cells. Carr said reports of people confined for more than 20 hours each day “doesn’t square” with what he’s been told.

DOC spokesperson John Beard said the amount of time inmates spend out of their cells varies on the day and whether they take part in programs or have job assignments. Recreation time is scheduled for three days each week at the prison in Portage, but Beard said it has been canceled on occasion due to the staffing shortage.

Carr said corrections officers are maintaining professionalism despite the conditions. He added the number of incidents at state prisons isn’t falling, but “it’s not blowing up.”

Criminal justice reform advocates say the situation only increases tensions, including Gretchen Schuldt, executive director of the Wisconsin Justice Initiative.

“You put these stressful situations on both staff and inmates and don’t deal with it, I do not see a happy ending to that,” said Schuldt.

As for David Phillips, he liked working at the Douglas County Jail. But, he said he wouldn’t go back to work that many hours for what he was paid.

“If I really valued that money, I can find a job working 40 to 50 hours a week and not have to work 60 to 70 to make that, so that’s important to me right there is the child,” said Phillips, gazing at his daughter. “And, maybe another one eventually.”

Jails and prisons across Wisconsin will have to find ways to keep workers like Phillips or attract new officers to fill the growing number of openings.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.