A Dane County judge on Friday overturned the rape conviction of a man who has served 27 years in prison largely on the strength of a single hair after the FBI admitted its analyst’s conclusion tying Richard Beranek to that hair was flawed.

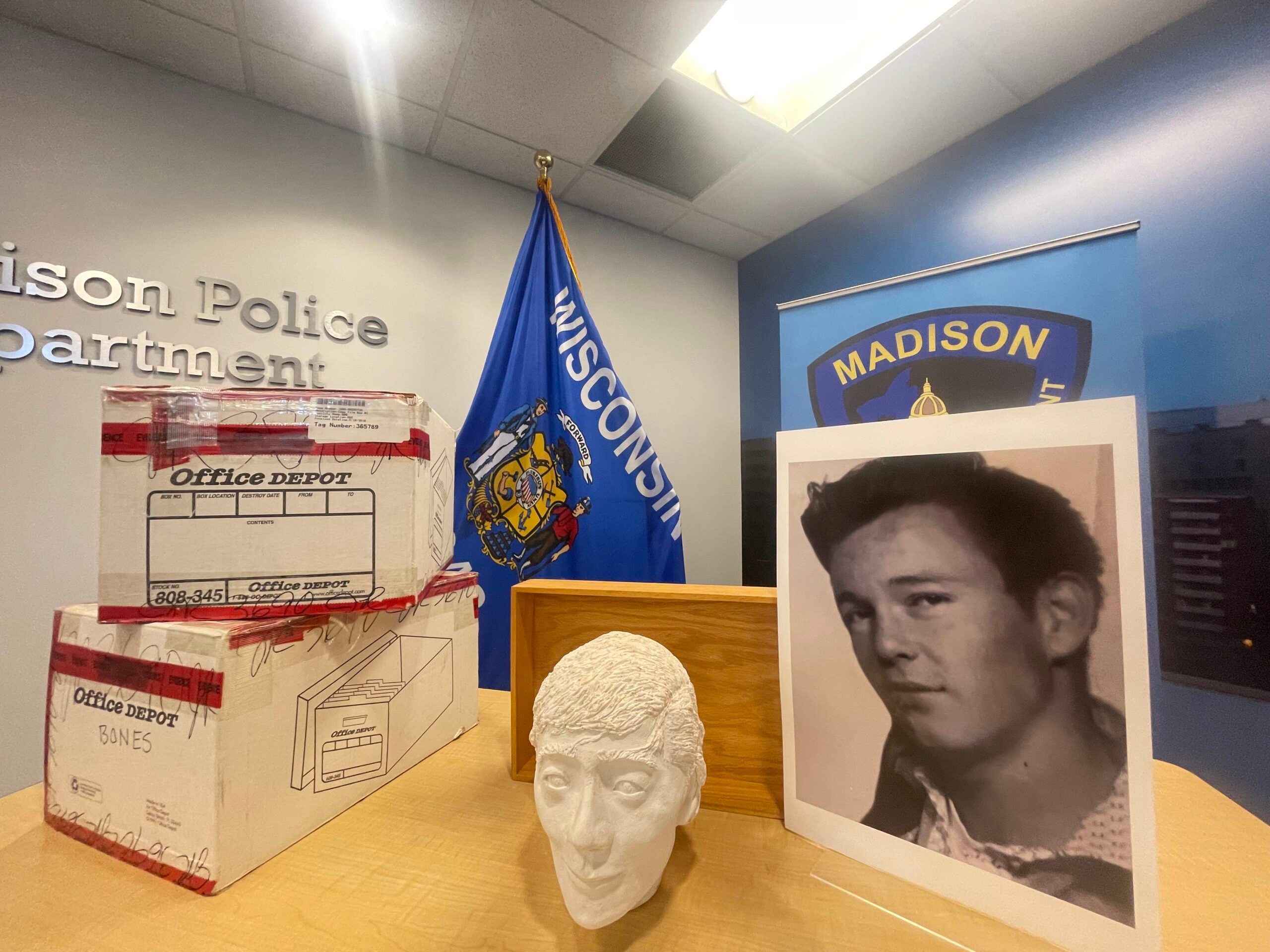

DNA testing has confirmed that neither the hair nor semen found in the perpetrator’s underwear left at the scene of the sexual assault matched Beranek, according to Beranek’s motion for a new trial.

Beranek, 58, was convicted in 1990 of raping a rural Stoughton woman in her home in 1987. He was serving a 243-year sentence imposed by Dane County Circuit Judge Daniel Moeser, now a retired judge, who issued the decision Friday to grant him a new trial.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“The hair evidence was an important part of the state’s case,” Moeser wrote. “There is no way to be sure as to how much weight the jury gave to the hair evidence. But based upon the totality of the evidence, one cannot conclude that the hair evidence was insignificant.”

State Department of Justice spokesman Johnny Koremenos said the agency is still reviewing the judge’s decision to determine whether to retry Beranek. Keith Findley of the Wisconsin Innocence Project said Friday the defense will file a request to let Beranek be released on bail.

Friday’s decision was at least the third time in Dane County that a conviction was overturned based on DNA evidence that contradicted earlier microscopic hair comparisons by the FBI or the Wisconsin State Crime Laboratory.

About 20 percent of the DNA exonerations nationwide have involved faulty hair analysis, according to the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. In April, the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism revealed there are at least 13 cases involving faulty microscopic hair comparison by the FBI in Wisconsin.

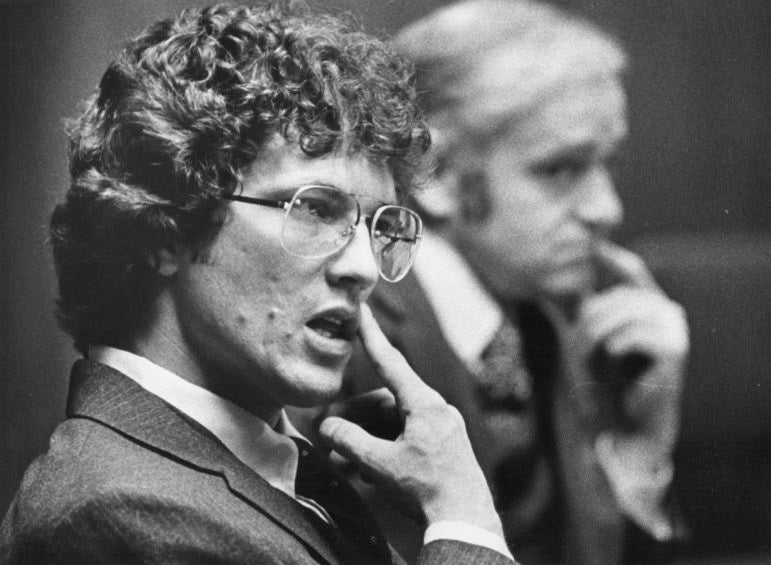

Richard Beranek sits with his attorneys, from left, Jarrett Adams, Keith Findley and Bryce Benjet in Dane County Circuit Court on Feb. 14, 2017. At right is the prosecution team, Assistant Attorney General Robert Kaiser and Assistant Dane County District Attorney Erin Hanson. Coburn Dukehart/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

The agency has acknowledged the technique can be used to identify the race of the person or the area of the body from which it came — but not an individual.

Moeser cited both the FBI’s admission of error and the DNA test results as tipping the balance in Beranek’s favor.

“If we just had the FBI letter commenting on the testimony of (analyst Wayne) Oakes at trial, this would be a very difficult decision,” the judge wrote. “However, we also have the evidence that the hair which was allegedly that of the defendant’s at trial is now known not to be that of the defendant.”

In Beranek’s case, the FBI analyst’s conclusion that hair from the scene “matched” Beranek helped overcome testimony from six people who said the suspect was 600 miles away in North Dakota at the time of the 1987 sexual assault and a belated identification by the victim, whom the judge labeled “an extraordinary witness.”

Assistant Attorney General Robert Kaiser, who prosecuted Beranek 27 years ago, represents the state, along with Dane County Assistant District Attorney Erin Hanson.

Beranek is represented by Findley and Cristina Bordé of the Wisconsin Innocence Project, and Bryce Benjet and Jarrett Adams of the New York-based Innocence Project.

“Obviously we’re thrilled,” Findley said. “It is the correct ruling. It’s the only ruling that the facts of this case would permit.

“We’re just grateful that the system responded to what was undoubtedly a miscarriage of justice.”

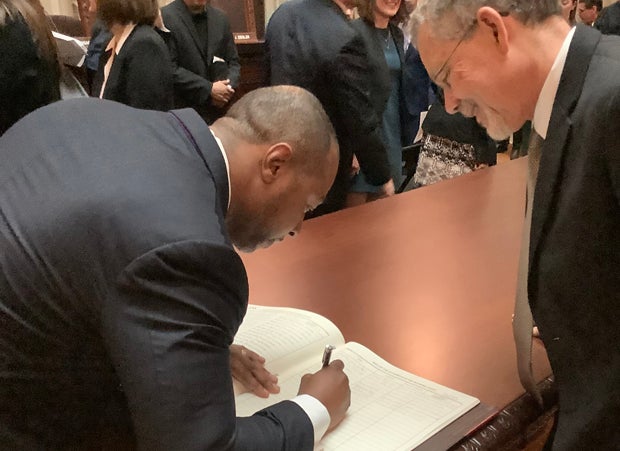

Friday morning, when Beranek’s attorney Jarrett Adams gave him the news, Adams experienced a familiar feeling. Adams himself had been wrongfully convicted of sexual assault in Wisconsin, serving seven years in prison before his release in 2007. He now works as a lawyer for the New York-based Innocence Project.

“He was very emotional. He’s been in prison since 1989,” Adams said. “So a lot is going through his mind right now, you know? For me, having gone through it before myself … it wasn’t real to me until I saw myself walking out of that prison and those gates, those bars, those bricks of wall and concrete were getting smaller and smaller and smaller every time I turned around, and the further I stepped away from them.”

Adams added that he hopes the decision will spur prosecutors in Wisconsin and elsewhere to help defendants challenge their convictions based on flawed hair evidence.

“There are other people just like Richard who are fighting to get their convictions overturned,” he said. “There are other people like Richard who don’t even know where to begin to fight to get their conviction overturned. So I hope that the onus is taken on by the state and I hope that they do their investigation … and not make guys argue and litigate these cases for decades at a time.”

Beranek is latest reversal

The FBI’s use of microscopic hair comparison has been discredited in hundreds of cases nationwide.

In 2015, the FBI acknowledged that analyst Wayne Oakes’ testimony in the Beranek case included “erroneous statements” in which he said or implied that the hair found at the scene “could be associated with a specific individual to the exclusion of all others.” Those statements “exceeded the limits of science,” the FBI said.

The Beranek case is among an estimated 3,000 slated for re-examination in which FBI hair or fiber analysis was used before 2000 when DNA testing became widely available. So far, 1,600 have been reviewed, according to Vanessa Antoun, an attorney with the national criminal defense lawyers group, which is participating in the effort.

As of 2015, the review found problems in more than 90 percent of the cases. Flaws have been identified in 13 Wisconsin cases including the Beranek case, Antoun said, but she declined to identify the others, citing a confidentiality agreement.

Rose Beranek and Desiree Burke, the mother and daughter of Richard Beranek, outside a Dane County courtroom Feb. 15, 2017. Dee J. Hall/Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism

During hearings in February and May, Kaiser raised questions about the handling of hair from the crime scene, zeroing in on the fact that one lab had placed them on Post-it notes before mailing them. Kaiser and Hanson argued in their objection to a new trial filed in April that the defense cannot prove the strand of hair Oakes linked to Beranek is among the hairs that now exclude him. The objection noted that labs handling the hairs reported either five or six strands of hair.

In their rebuttal, Benjet and Findley noted testimony from the February hearing that some hairs are so fine they are hard to count. Moeser sided with the defense, saying it had proven the hair that now excludes Beranek is the same one Oakes had claimed matched him back in 1990.

Desiree Burke said Friday she hopes to soon get to know her father, who went to prison when she was a little girl.

“I was never afforded that as a child. I never knew him,” she said. “And so my husband will finally get to meet him. My kids will finally get to meet him. So it’s exciting — very exciting.”

The Center’s reporting on criminal justice issues is supported by a grant from Vital Projects at Proteus. The nonprofit Center (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.