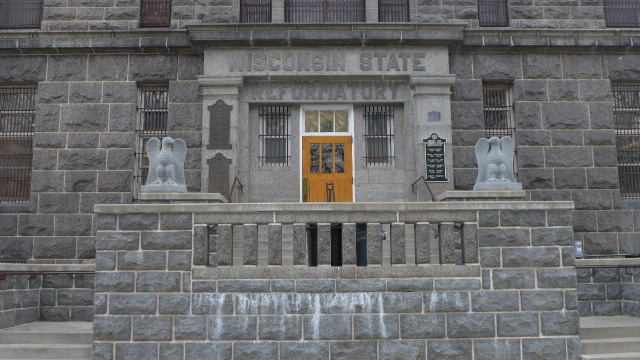

State and local leaders are doubling down on their calls to close one of the state’s oldest prisons, even as legislative efforts to do so remain stalled.

The renewed push comes as a staffing shortage and a months-long lockdown continues to plague the Green Bay Correctional Institution, located in the village of Allouez in Brown County.

A 2020 report commissioned by the state identified Green Bay as the Wisconsin prison most in need of replacement. It detailed numerous problems at the 125-year-old facility, including plumbing leaks, a lack of compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act and an outdated design that presents security risks.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Green Bay’s 50-square foot cells were designed to house one person each, but overcrowding has forced inmates to double up, the 2020 report noted. Even at single-cell occupancy, the review noted Green Bay’s facilities fell short of modern standards from the American Correctional Association.

As of last week, there were 982 men locked up at Green Bay, making the prison over capacity by 233 people. The prison’s “deplorable” conditions are a result of decades of neglect, said Rep. David Steffen, a Green Bay Republican.

“The Legislature, governors, both parties have responsibility for this situation,” Steffen said, noting that reports detailing Green Bay’s failings have been released under both Democratic Gov. Tony Evers and his predecessor, Republican Scott Walker. “We are not in a situation where there’s a debate anymore (about) the fact that it needs to be closed. It’s just about who’s going to stand up, who’s going to be the governor to make that decision.”

A longstanding budget issue

Steffen is among the state lawmakers who say it’s past time to shut down Green Bay, and to build a replacement facility elsewhere.

In the past, Steffen and other northeast Wisconsin representatives have suggested keeping the new prison in the same region, but in an interview Monday, Steffen said he’d be open to a broader range of locations.

Replacing the Green Bay prison could cost up to half a billion dollars according to the latest estimate, which is four years old. That funding is not included in Wisconsin’s current two-year budget.

In 2019, Evers rejected a budget provision that would have started the process of replacing Green Bay, by allocating $5 million to acquire land, extend utilities and put out a request for proposals for another maximum security prison. At the time, Evers wrote in his veto message he objected to building another maximum security prison while “we continue to explore needed criminal justice reform in Wisconsin.”

The governor’s office did not respond Monday to a request for comment about the future of the Green Bay Correctional Institution. Criminal justice reform advocates have joined in calls for Green Bay’s closure, although progressive groups including Ex-Incarcerated People Organizing of Wisconsin and WISDOM have argued against building a new facility.

Instead, activists like Sara Williams of Justice Organization Sharing Hope & United for Action, or JOSHUA, say the focus should be on reducing Wisconsin’s incarcerated population. JOSHUA has been among the groups holding weekly vigils outside the Green Bay Correctional Institution to call attention to conditions there.

“They have a huge mice infestation problem,” Williams said of Green Bay. “The toilets and sinks are backing up in certain areas. When you walk into the prison, it’s very dreary and dark … there’s not a lot of windows.”

Since June, inmates at Green Bay have been largely confined to their cells under conditions that the department refers to as “modified movement.” Those restrictions have included limitations on showering, recreation time and visitation. And for many incarcerated people, they’ve had a disastrous impact on mental health, said Brian Coombe, whose 21-year-old son is incarcerated at Green Bay.

“Even if they don’t typically have mental health illnesses, the lockdowns were torturous, mentally torturous,” Coombe said. “We’re putting people in cages.”

In the short-term, a focus on pay and conditions

In late October, Evers announced Wisconsin’s Department of Corrections was easing some lockdown restrictions at Green Bay and at the Waupun Correctional Institution, another maximum security lock-up. Meanwhile, Evers said the department is working to hire more security staff, with the goal of making it safe for prisons to resume normal operations.

“I will accept the department’s recommendations for capital project options if these efforts are unsuccessful in reducing the vacancy rate and adequately improving staffing numbers given the structural challenges and limitations of our correctional institutions,” the governor said in an October statement.

The governor pointed to raises for corrections officers that took effect this summer, and include extra pay bumps for people who agree to work in higher security facilities. Even so, more than 40 percent of corrections positions remained vacant at Green Bay as of mid-November. That’s slightly higher than the vacancy rate at Wisconsin’s two other maximum security prisons, which reported between 36 and 39 percent of those positions were unfilled.

Steffen argues replacing Green Bay will help ease some of the prison system’s staffing woes, since a facility with a more modern design could include better sight lines and allow fewer guards to monitor more inmates. He says raises alone aren’t enough to entice people to work in a “pressure cooker environment.”

“It is a dangerous, dangerous, unhealthy environment there and so it’s not good for the inmates and, as one would expect, people don’t want to work there either,” Steffen said.

That environment is one that Allouez Village President Jim Rafter describes as a “powder keg waiting to blow.” He says Brown County deputies have been responding to an increasing number of calls at the prison and he worries about violence spilling into the broader community.

Rafter says, while he doesn’t have a position on whether another prison should be built to replace Green Bay, it’s clear the existing facility is past due to be shut down.

“GBCI is a terribly dangerous place for those who work there, for those who are incarcerated there, for those who visit there,” he said. “We have to remember, we’re dealing with people’s lives. We’re not dealing with a political football.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.