Beverly Walker doubts that the governor’s plan to abolish the Wisconsin Parole Commission will add efficiency to a sluggish system, and she suspects it would make qualifying for parole even more difficult.

Her husband, Baron Walker, has been imprisoned for nearly 22 years on a 60-year sentence for two armed bank robberies. Since 2011, he has been eligible for parole under Wisconsin’s old sentencing scheme, which allowed inmates to petition for release after serving one-fourth of their time.

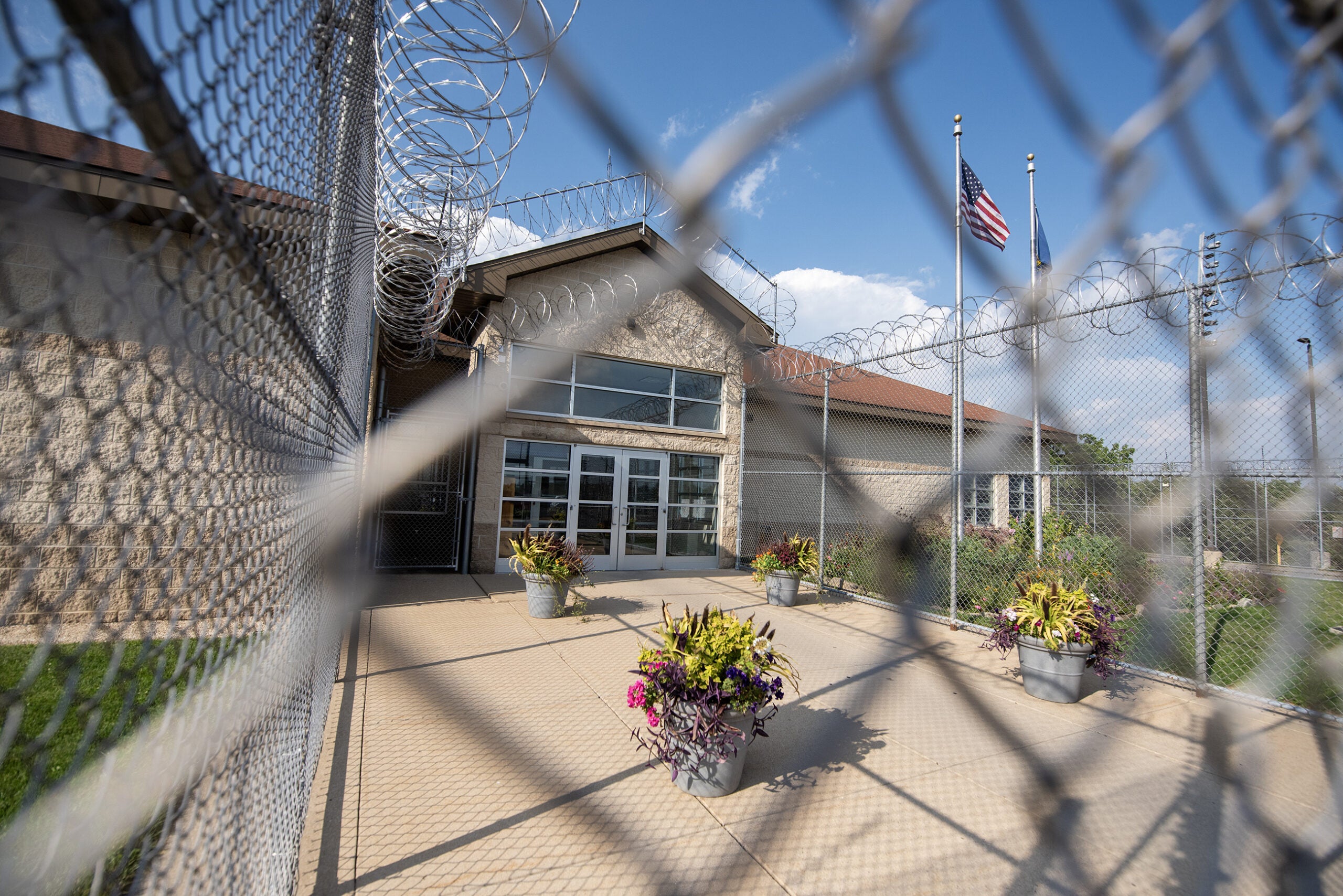

Baron Walker has met required conditions for behavior and all programming that has been recommended, including a high school equivalency degree and vocational training, according to a 2015 report from the Parole Commission. He now resides in the minimum security Oakhill Correctional Institution, whose primary focus is to “prepare offenders for release into the community.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“You take full responsibility for your crimes and for the harm you have caused the victims and others. You have engaged in a considerable amount of positive growth and maturity during this incarceration,” the report stated.

Despite that, the commission concluded that Walker’s criminal history — including a previous stint in prison — and the severity of his crimes means “serving additional time for punishment is warranted.”

“It’s horrible that we’re not together, reunited, by now because he’s met the requirements of the law he was sentenced under,” said Beverly Walker of Milwaukee, who has been a single mother to their five children, who now have six children of their own. “He’s met everything that he was supposed to meet. So it’s confusing to the children, you know, when they see that he’s done what he’s supposed to do and he’s still locked up.”

Gov. Scott Walker is proposing to abolish the Parole Commission and put the decision about whether to release thousands of parole-eligible prisoners into the hands of a gubernatorial appointee. Walker spokesman Tom Evenson said the change would “streamline” the parole process.

The Parole Commission has operated short-handed during Walker’s tenure; the eight-member board currently has five vacancies.

“It just seems like everything is stagnated when it comes to parole-eligible inmates already, so it’s hard to tell if eliminating the commission is going to help this process move forward or not,” Beverly Walker said.

Under the Republican governor, the commission has released far fewer offenders than it did under his predecessor, Democrat Jim Doyle. Walker also killed an early-release program launched by Doyle, has refused to issue any pardons and, as a state lawmaker, spearheaded the 1998 Truth in Sentencing law, which abolished parole for most prisoners.

One inmate advocate, the Rev. Jerry Hancock, said cutting funding for parole considerations even more could make a “broken and unfair system” worse.

Parole Plan Raises Questions

An international parole expert said if adopted, Wisconsin’s system would be “a very unique set- up” and one that could be less fair to parolees and more prone to political influence.

“In my history in criminal justice of 30-something years, I’ve seen them (states) add to parole boards and I’ve seen them take away from parole boards but I’ve never seen a situation where they limited the decision-making to one person,” said Monica Morris, chief administrative officer of the Association of Paroling Authorities International, a Huntsville, Texas-based group that helps develop research-based parole policy.

“In my opinion, that is too much power to give to one person,” Morris added. “The whole concept of a parole board is you have two or three or five or seven (people) where you have a deliberative process where people are making a collaborative decision.”

Cecelia Klingele, an assistant law professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said she cannot imagine how one person could give “fair and full consideration” to the “significant” number of people who are currently parole eligible.

Department of Corrections spokesman Tristan Cook said about 3,000 people are serving “parole eligible” sentences in Wisconsin but he did not know how many of those are currently eligible for release.

While no inmate is “entitled” to parole, “they do have a legal right to fair assessment of their case,” said Klingele, who specializes in criminal justice administration and community supervision.

Walker’s two-year budget calls for closing the Parole Commission on Jan. 1, 2018 and moving its duties to the DOC. That would save an estimated $1.8 million over two years, including elimination of 13 positions, Evenson said. Decisions on whether to grant paroles would be handled by a “director of paroles” appointed by the governor, he said.

Evenson said the proposal is a “common sense change” since the chairperson of the Parole Commission, who makes the final decision on releases, is already a gubernatorial appointee.

According to a national survey published in 2016, no state had abolished its parole board in the previous 15 years. Wisconsin was among five states that did not complete the survey, which was conducted by the Robina Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Justice at the University of Minnesota Law School.

Parole board members generally have set terms and can be removed only for cause, creating at least some political independence, said Morris, who served under three governors during her 12 years on the Florida Parole Commission.

Putting the board under the purview of the DOC, she said, could reduce some of that independence.

“I would not want … the people that are holding the key to be included in the decision-making process,” Morris said. “What if they have an incentive to keep them in or an incentive to let them out?”

Walker: Boost Earned Releases

The governor also plans to expand earned-release programs that allow nonviolent offenders to cut short their time in prison by completing drug or alcohol treatment or the military-style Challenge Incarceration Program.

Whether those changes will result in paroles for “old-law” inmates convicted of crimes committed before 2000 remains unclear. For crimes since the beginning of 2000, offenders fall under Truth in Sentencing, which requires them to serve their full time in prison, with no opportunity for parole, unless they complete an earned release program.

The budget proposal calls for expanding the state’s earned-release programs by 250 inmates by adding 16.25 more positions to the DOC, Evenson said. Such programs allow inmates to cut their incarceration time by completing substance abuse treatment or other programming. According to DOC figures, 1,637 inmates were released in 2016 under these programs, in which remaining time behind bars is converted into parole or supervised release.

The expansion is expected to save money by reducing the number of beds rented from county jails to alleviate crowding. The net savings is expected to be $3.7 million over two years, Cook said.

Number Of ‘Old-Law’ Releases Unknown

According to data from the Wisconsin DOC, 1,002 paroles were granted between July 2011 — when Kathleen Nagle, Walker’s first pick to lead the Parole Commission, took office — and the end of 2016. The DOC database does not disclose what proportion of offenders were old-law prisoners and which were sentenced more recently.

About half of the paroled offenders, or 491, participated in such programs, which include the Wisconsin Substance Abuse Program and the Challenge Incarceration Program, Cook said. Both Cook and Evenson emphasized that under earned release, offenders’ length of sentences do not change; time in custody is cut and converted to time outside of prison under supervision of a probation or parole agent.

Another 141 offenders had reached their mandatory release date, meaning the DOC was legally obligated to parole them, according to department data. Under the old law, inmates were eligible for parole after serving one-fourth of their sentences and had to be released under most circumstances after serving two-thirds of their sentences — factors that judges kept in mind prior to 2000 when sentencing offenders. People on parole are subject to conditions which, if violated, can land them back in prison.

Advocates for parole-eligible inmates had mixed reactions to Walker’s proposal to kill the Parole Commission.

Hancock, director of the Prison Ministry Project in Madison and a former prosecutor, said the change could make it harder for old-law inmates to gain release. Hancock said the proposal shows Walker’s “complete contempt for the law and the basic justice of parole,” adding, “His continuing refusal to grant the fair hearing that sentencing judges promised the nearly 3,000 inmates still eligible for parole is cruel, inhumane and immoral.”

David Liners, state director of Wisdom, a statewide faith-based group, said it is unclear whether the changes would speed up or slow down parole considerations for old-law inmates.

“It is very hard to imagine that they will deal with parole requests more efficiently with less people,” Liners said.

However, leaving the decision within the DOC could avoid the “bureaucratic nightmares” that some inmates encounter in qualifying for release, he said. Some old-law inmates have said they cannot access programming ordered by the Parole Commission because the DOC does not make it available to them.

“Instead of abolishing the independent Parole Commission,” Hancock said, “the Legislature should require an immediate review of all those prisoners who are eligible for parole and determine who can be safely returned to their families and communities.”

He said there are hundreds of parole-eligible inmates who are already in minimum security or even working in the community. Releasing them from prison — where costs to house them are estimated at $37,994 a year per inmate — would save the state millions of dollars, Hancock said.

Rate Of Parole Unclear

An analysis by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism shows the Parole Commission granted 11.9 percent of parole petitions in 2016 — a number that had been in the single digits for four and a half years. That includes inmates who petitioned more than once in a year.

Whether Wisconsin is typical of other states in its parole release rate is unclear. Wisconsin did not report parole numbers in the most recent U.S. Bureau of Justice Assistance report.

Even so, it is nearly impossible to compare state correctional systems because of variations in how such data are reported, according to a 2015 investigation by The Washington Post and The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news outlet that reports on criminal justice issues.

But the investigation did find one common theme: “In many states, parole boards are so deeply cautious about releasing prisoners who could come back to haunt them that they release only a small fraction of those eligible … even those who pose little danger and whom a judge clearly intended to go free.”

Liners said a similar dynamic appears to be at work in Wisconsin, with a Parole Commission “so risk averse that they don’t want to release anyone.”

In the past, the DOC defended the slowing pace of paroles for old-law prisoners, saying those who have not been released earlier have committed the most serious crimes. A DOC report on parole-eligible prisoners as of 2014 found that 73 percent were incarcerated for forcible rape, homicide or non-negligent manslaughter.

Days From Parole, Offender Told ‘No’

Adan Castellano, an old-law inmate, was 17 years old in 1993 when he and six others were involved in the beating of two teens they suspected of being members of a rival gang. One boy, who was determined not to be a gang member, was killed.

Castellano was convicted in Racine County Circuit Court of reckless homicide and other counts and was sentenced to 45 years in prison. After being locked up for 24 years, Castellano — now 41 years old — is a model prisoner, according to his parole report. Considered a low risk to the public, Castellano has earned the right to work for a landscaping company in the Madison area.

“You entered the system at a young age, turned your life around, completed programming, satisfied all owed obligations, saved money for release, secured an approved release plan and demonstrated success at multiple minimum community custody sites with work release,” Parole Commission member Danielle LaCost wrote.

She recommended that Castellano, currently housed at the fenceless Oregon Correctional Center, be released Jan. 24.

However, as one of his first orders of business, Walker’s newly appointed interim Parole Commission chairman, Douglas Drankiewicz, on Feb. 1 rejected that recommendation. He wrote that Castellano needed to serve more time in part because of “the nature and severity of the crime (the senseless taking of an innocent life).”

Lupe Castellano of Waukegan, Ill., who was 1 year old when her brother was sent to prison, said the parole denial was devastating to Adan’s nieces and nephews, four siblings and especially his mother.

“It’s been really hard on my mom,” she said. “Especially to know that she was finally going to have her son home — and to have it taken away like that.”

She said eliminating the Parole Commission would probably result in fewer paroles because it would be impossible for a single official to track the progress of thousands of inmates.

“Your life would be in one person’s hands,” Castellano said.

No Release After Inmate Meets All Conditions

Liners said many old-law inmates and their families complain that they are repeatedly denied parole even after demonstrating evidence of rehabilitation and little risk of re-offending.

Kim Szemborski is one such case. Szemborski is serving a 64-year sentence from Racine County as a habitual criminal for a 1987 armed robbery and an escape in which he stole a car with three people in it. They were released unharmed a few blocks later, according to a 2015 Parole summary of Szemborski’s history written by LaCost

The report praises Szemborski for his exemplary behavior and his history of work, including at jobs outside of prison. Szemborski also was credited with extensive participation in programming and treatment.

“There are no identified programs remaining,” LaCost wrote.

Nevertheless, LaCost wrote that the commission had decided Szemborski must serve additional time, noting the seriousness of his crimes and criminal history stretching back to the early 1970s — including an armed robbery committed while on parole for earlier crimes.

“Serving additional time in a productive manner, achieving reduced custody with work release and further preparing for release will help to demonstrate a mitigated level of risk,” the commissioner wrote.

Szemborski, now 62, was recommended for release in 2011, but Walker appointee Nagle overruled that, according to Szemborski’s unsuccessful court challenge of the decision. He has been denied parole six times since then. His mandatory release date is in 2030.

“The reason they (inmates) are given so often is because of the severity of the crime or due to insufficient time served,” Liners said. “These things always harken back to the original crime, and that’s the one thing these guys can’t change.”

The Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism’s reporting on criminal justice issues is supported by a grant from the Vital Projects Fund. The nonprofit Center (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.