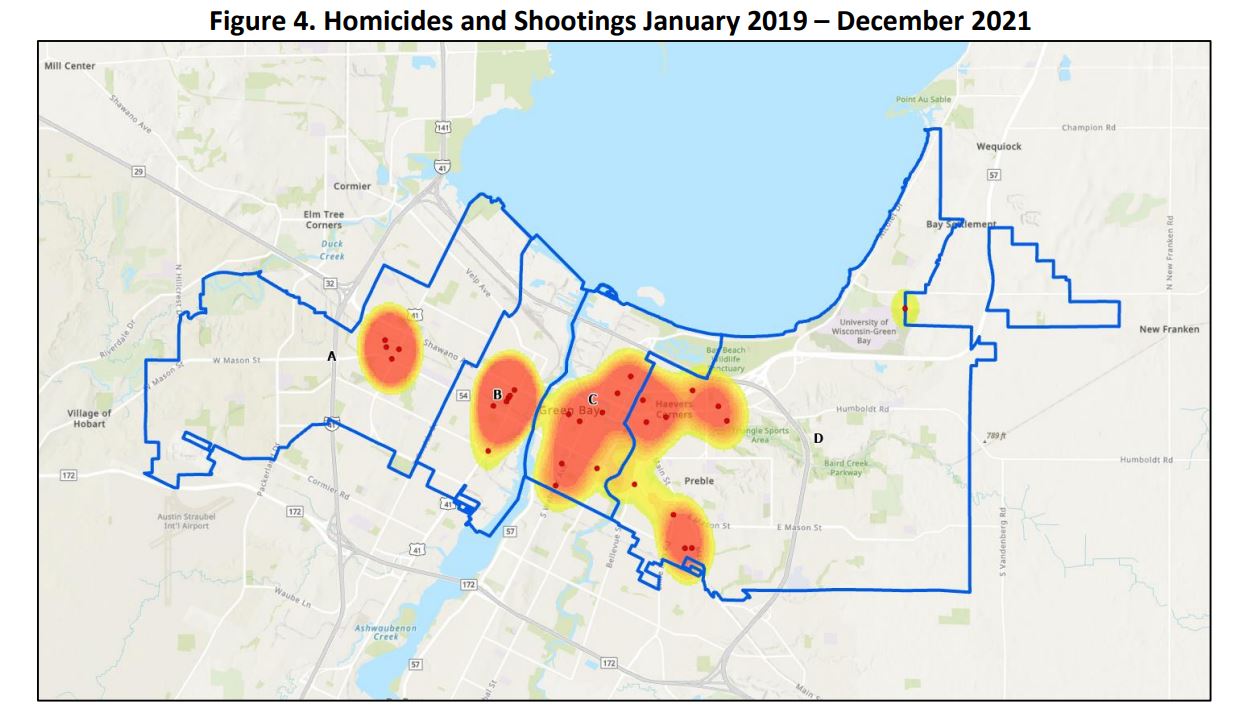

A study of gun violence in Green Bay finds it is driven by a small number of young men involved in gang activity, and that most gun violence happens in retaliation against earlier gun violence.

Officials hope to use the data to shape the city’s crime policies and to improve violence prevention efforts. The Green Bay City Council this week heard recommendations from the director of the National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform, which authored the study, including a recommendation that the city create a gun violence reduction unit in its police department, improve intelligence gathering and expand community investments in violence intervention services.

The study looked at every instance of gun violence in the city from 2019 through 2021, reviewing not just homicides and gunshot injuries but also every report of shots fired. The institute’s director, David Muhammad, presented the findings and issued a written report.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The analysis finds that a majority of both victims and suspects were Black, and the overwhelming majority — nearly 90 percent — were male. Most were between the ages of 18 and 34; relatively few were minors. The findings connect the violence to activity of 11 gangs or social groups in the city. (Muhammad noted that “gang” has a legal definition that isn’t always met by the loose social connections that form some of these groups). And most victims and offenders had a previous criminal record.

Muhammad called this group of men a “small, small population” and noted that the vast majority of Black men in the Green Bay are not connected to gun violence at all. But he said the social ties within this small group of offenders also means there are clear patterns of behavior that precipitate the violence.

“A good number of these incidents could be identified ahead of time,” he said. “The violence is somewhat predictable, and therefore preventable.”

Most of the shootings happened in retaliation against earlier shootings. Subjects often make threats on social media, Muhammad said, “vowing revenge.”

Better intelligence-gathering capabilities create a window of time when authorities can intervene and prevent the next act of violence, Muhammad said, through community and nonprofit programming.

This “violence interrupter” model of reducing gun crimes has gained traction in some large U.S. cities in the last decade, though evidence on its effectiveness is mixed.

With a population of around 100,000 people, Green Bay is a relatively small city. Its study of gun violence comes amid a national spike in murders that has become an especially serious concern among residents of large cities. Green Bay’s homicide rate is well below the national average, and the number of homicides in the city declined in 2021. That defies the national trend and the trends in some other Wisconsin cities, notably Milwaukee.

The fact that violence is relatively rare in Green Bay, Muhammad said, is what allowed researchers to do an extensive analysis of all gun violence and not just murders or gunshot injuries.

Green Bay Police Chief Chris Davis, who was hired for the job less than a year ago, told the council that his department’s neighborhood response team is working to build connections in the community and get to know the people who are most at risk of being either a victim or a perpetrator of gun violence.

The next step, Davis said, is “how do we try and identify some opportunities to direct people to services — job training, mental health help, addictions help, whatever it is — to get them out of that pipeline before it’s too late.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.