Wisconsin is America’s Dairyland. It’s a title we take seriously.

The state is home to more than 1 million cows that produce 2.44 billion pounds of milk per month. We even host the annual World Cheese Championship and World Dairy Expo.

From milk to cheese to butter, the dairy industry is a cash cow for the state, generating $45.6 billion a year for the state’s economy.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

For Wisconsin’s state legislators, it’s an industry worth protecting. And its importance can be traced through a history of sometimes oddball laws intended to protect it.

Ed Piehl, of Columbus, Ohio, reached out to WPR’s WHYsconsin about one such law.

He visited his grandparents in Kenosha as a child, and remembers the margarine being white instead of yellow. His grandfather had told him, “It’s a Wisconsin law.” So Piehl asked WHYsconsin, “Is that true?”

It reminded me of a similar story I’d heard from my father-in-law Rob Howell, who spent most of his early life growing up in Kenosha. One of his chores as a young boy was to mix the yellow dye into the oleo — a colloquial term for margarine.

“It came in these rectangular 1 pound packages with a little bead of yellow dye, and you had to break that bead and then spread it through the pound of oleo,” Howell recalled.

While the task took about 10 minutes, Howell said it felt like an eternity as a child. And the chore wasn’t done until all the color was evenly mixed in.

“It was a god-awful mess, because by the time you’d squeezed this oleo for 10 minutes and it’s softened way up, then you had to squirt it out into some sort of container,” he said. “It was always pretty unappetizing. But it was super unappetizing when it was white.”

Neighboring states repealed laws banning and taxing yellow margarine much earlier than Wisconsin, driving many residents — like the Howells — to cross state lines to buy the pre-mixed, cheaper goods.

Border towns like Waukegan, Illinois — some 16 miles south of Kenosha — boasted pop-up oleo stands, advertising their product to traveling Wisconsinites.

“If we knew ahead of time that we were going to (Waukegan), we’d asked our neighbors if they wanted us to pick up a few pounds of colored oleo for them,” Howell said. “And so we often came back with quite a haul of this illegal margarine.”

Wisconsin’s oleomargarine laws

Wisconsin started regulating the manufacture and sale of margarine in 1881, according to the state’s Legislative Reference Bureau, or LRB. While the laws have varied over the years, the intent was simple: ensure fair prices for dairy products and prevent fraud.

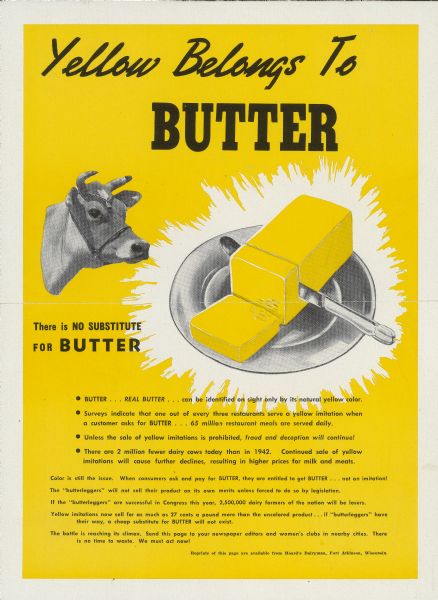

In the late 1800s, dairy substitutes like margarine were often sold as the real thing, prompting states across the nation to regulate the products.

“Butter and cheese were filled with lard and water and oleomargarine was sold as butter. As a result, legislation against oleomargarine became commonly accepted as a necessary part of the legislation against fraud,” a 1965 LRB report reads.

Dave Driscoll, a curator at the Wisconsin Historical Society, said once the recipe for margarine was cemented, the best argument against it was that it was pretending to be something it’s not — and when it was yellow, margarine easily passed as butter.

“(Margarine) is kind of a pasty white by itself. In the literature it’s referred to as things like a corpse-like white. So, I think they felt that as long as it didn’t look appealing, it didn’t look like something delicious for your toast … that that was good enough,” Driscoll said. “It would help if you taxed the producers of it — and many states, including Wisconsin, did.”

But margarine’s popularity took off in the 1940s and ’50s after the product improved and World War II led to a nationwide shortage of butter. As people developed a taste for oleo, constituents grew tired of the restrictions, prompting many states to repeal their bans on yellow margarine.

“Throughout the Great Depression, and then World War II rationing, more and more people actually had experience consuming margarine,” Driscoll said. “So it was not something that more and more people felt was unacceptable. It was like, ‘Well, I’ve been eating this for years now. You know, it wasn’t all that bad. And it’s significantly cheaper. So I should be able to buy this.’ So there was kind of this changing public sentiment.”

In 1950, the federal government repealed its taxes on oleo. By 1953, only Minnesota and Wisconsin had laws prohibiting the sale of yellow margarine. In 1963, Minnesota repealed its oleomargarine laws leaving Wisconsin as the lone holdout.

But in 1967, Wisconsin joined the rest of the nation in allowing the manufacture and sale of yellow margarine.

I asked Driscoll why it took the Dairy State so long: “I think, in general, it’s safe to say that the dairy interests in the state were as strong or stronger here than in most other states,” he said.

And there are still laws regulating margarine in effect today that:

- Prohibit restaurants from serving margarine unless specifically asked for.

- Ban the serving of margarine to students, patients or inmates in state institutions unless medically necessary.

- Set out strict requirements for the amount of dye included and how the product is packaged and labeled.

Current laws make butter the go-to in terms of spreadable fats in Wisconsin.

It’s a welcome change for Howell, who vividly remembers trying butter for the first time at school when he was 7 years old.

“I got one day at Forest Park Elementary School, a hot lunch … and I tasted that and was immediately impressed at how much better it was than margarine,” he said. “I went home with that and was told by my mom that butter was too expensive and unhealthy.”

But once it was up to him, he steered clear of oleo.

“I haven’t eaten margarine, at least knowingly, for probably 50 years. I think it’s just terrible stuff,” said Howell.

Truth in labeling

A set of similar laws that would bar foods from being labeled as meat, milk and dairy if they don’t contain those foods are before the Wisconsin Legislature.

It would include products like the meatless “Impossible Burger” and milk alternatives like soy, almond and oat milks.

The bills, deemed the “Truth in Labeling” laws, passed the Assembly in June, but have yet to be voted on by the state Senate.

According to the Associated Press, those in support of the bills say they’ll help protect the state’s agriculture economy, educate consumers about misleading food labels and put pressure on the federal government to take similar action. Those opposed, including groups that promote plant-based food, say the bills are unnecessary, bad for Wisconsin businesses and consumers, and an infringement on free speech rights.

State Sen. Howard Marklein, R-Spring Green, is one of the lawmakers to introduce the bills. He said the bills would directly impact farmers and food processors in his district.

“They feel very strongly about the integrity of food labeling and are frustrated by the misleading labeling that has invaded dairy and meat cases throughout our grocery stores,” Marklein said in a press release when he announced the bills. “It’s disappointing when you open a carton of ‘ice cream’ and discover that you mistakenly bought a flavor-less, dairy-free alternative, rather than the creamy, delicious treat you expected.”

For Driscoll, the parallels to the state’s oleomargarine laws are evident.

“There’s two valid ways to look at it,” he said. “One is it’s all about protecting the consumer, everyone has the right to know everything. And usually the people who advocate that position, also know that if the consumer knows everything, they’re likely to act in a way that’s congenial to that. And then there’s the other point of view, which is it’s not really appropriate to use legislation to cement a business advantage. And that’s to me what’s really fascinating about the oleo story.”

This story was inspired by an audience question as part of the WHYsconsin project. Submit your question at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it.