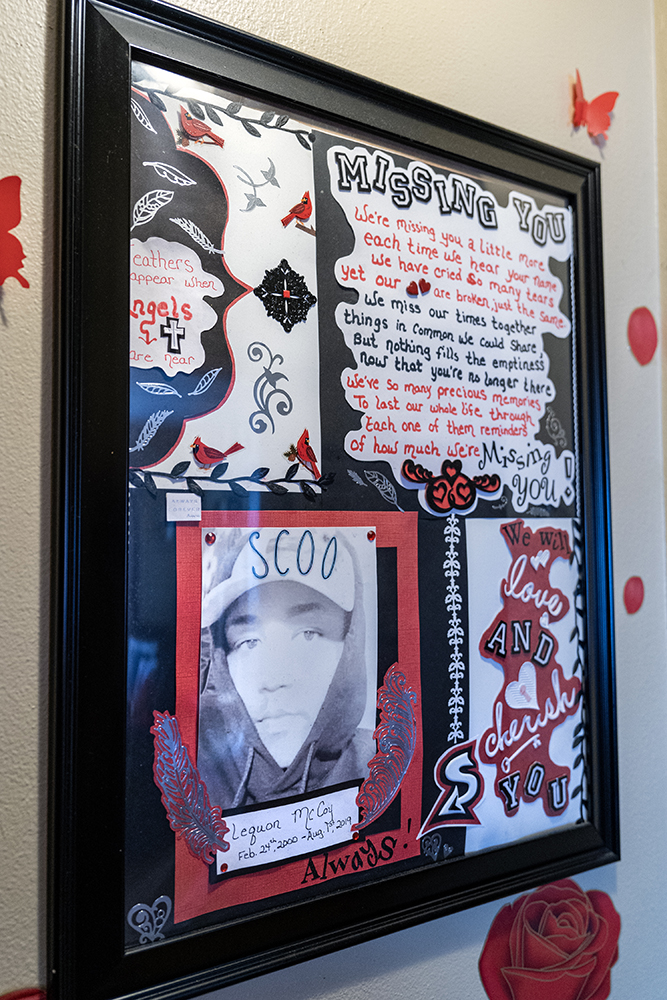

At 1:06 a.m. on Aug. 1, 2019, Le’Quon McCoy was driving through a North Side Milwaukee intersection when the driver of a stolen Buick Encore ran a flashing red light and crashed into McCoy’s Jeep Renegade.

The speeding driver, who was fleeing police, hit McCoy’s Jeep so hard that it bounced off a tree on one side of the road and into a parked car on the other side. McCoy, 19, died at the scene.

“He got off work around like 9 or 10 at night. He stopped here to see me,” his mother, Antoinette Broomfield recalled. “He told me he would be to see me the next day, and he was going to drop a friend off at home. And that’s the last time I heard from him.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

The death of McCoy — described as a warm, outgoing, “big teddy bear” with many friends — inflicted a still-unhealed wound, Broomfield said.

A court sentenced Aaron Fitzgerald, the driver of the stolen Buick, to 10 years in prison and eight years of extended supervision related to McCoy’s death.

But Broomfield’s quest for accountability didn’t end there. She’s suing the city of Milwaukee and four officers who pursued Fitzgerald. Broomfield, whose attorney was present while she spoke to Wisconsin Watch and Wisconsin Public Radio, said the officers could have averted the tragedy by calling off a high-speed pursuit that spanned residential and commercial streets.

Broomfield’s lawsuit, filed in March 2022, comes during a 20-fold surge of police chases in the years since Milwaukee loosened restrictions for pursuits — reaching an average of nearly three per day in 2022, according to Milwaukee Police Department records.

The department engaged in 1,028 chases in 2022, up from 50 in 2012, according to data provided through an open records request. The 2021 tally was even higher: 1,078. It eclipsed all years since at least 2002, according to a 2019 Milwaukee Fire and Police Commission report.

The trend unfolds as Milwaukee grapples with a spike of reckless and deadly driving.

More pursuits mean more chances of injuries to fleeing suspects, officers and other responders and third parties like McCoy who become unwittingly involved.

In 2022, for example, 132 pursuits injured at least one suspect, and 36 pursuits resulted in at least one third-party injury, data show. Officers faced injuries in five pursuits.

During more than 6,600 pursuits from 2007 to 2022, fleeing suspects were injured in 13 percent of pursuits, followed by third parties (4 percent) and officers (1 percent), according to an analysis of the 2019 Fire and Police Commission report and other data obtained by Wisconsin Watch and WPR.

The toll of Milwaukee pursuits hasn’t ebbed this year. Four this year were recorded as fatal through June 26, the data show.

“There are good reasons not to permit the escape of dangerous criminals,” Broomfield’s lawsuit says. “But sometimes it is preferable to simply prolonging the danger to innocent motorists and pedestrians that occurs if a pursuit is not terminated.”

Milwaukee police pursuit data incomplete

Milwaukee’s full count of police pursuit casualties is unclear. Data provided to Wisconsin Watch and WPR show whether a pursuit ended in “injury” or “death” without specifying the number of people involved in each incident.

For example, although three people died last year when a pursued Toyota Avalon plunged off a bridge and erupted into flames, police records for that crash say it ended in “subject injury,” “violator death” and “third party injury.” One woman was hit and injured as the driver fled police, according to media reports.

Also not logged in the data: instances of injuries occurring just after a pursuit was canceled.

Official police records often paint an incomplete picture of the impact of pursuits, said Jonathan Farris, chief advocate for the Wisconsin-based Pursuit for Change, which seeks to limit police pursuit casualties. Farris lost his son in 2007 when a driver fleeing a Massachusetts State Police trooper crashed into a cab his son was in, killing him and the cab driver.

Farris points to a 2015 USA Today investigation that found the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration significantly undercounted police pursuit deaths over several decades.

“Most of us who have been following this for a fair number of years have seen more than enough examples of pursuits that were not logged,” Farris said.

In Milwaukee, a June 7, 2019, pursuit severely injured one officer, Matthew Schulze, and killed another, Charles Irvine Jr., according to media reports. But the records show only one pursuit that day — with no officers injured.

Milwaukee tightens, then loosens pursuit policy

The Milwaukee Police Department cites a nationwide surge in deadly driving as one of several factors leading to more police pursuits. Milwaukee’s loosened restrictions on pursuits have permitted officers to crack down on reckless driving and vehicle-based crimes in recent years, said Inspector Craig Sarnow, who has spent much of his 24-year department career in roles that monitor and investigate pursuits.

“I can recall back to my time as a patrol sergeant, when the policy was more restrictive,” he said. “We used to have individuals that would try to bait Milwaukee police officers into getting into pursuits knowing full well that we couldn’t because our policy was so restrictive.”

But safety advocates say Milwaukee’s previous, more restrictive policy — adopted in 2010 under then-Chief Edward Flynn following a string of deadly pursuits — made progress that has since been erased. The policy allowed pursuits in narrower scenarios, generally when an officer had probable cause that a violent felony had occurred or was about to occur — or if someone posed a “clear and immediate threat to the safety of others.”

Police under Flynn’s policy made fewer arrests related to pursuits compared to before the policy was implemented, but they also saw fewer pursuits ending in injuries.

A policy tweak in 2015 allowed police to pursue a vehicle if the vehicle was involved in a violent felony. That change allowed officers to pursue carjacked vehicles. Pursuits more than doubled that year, compared with 2014.

Milwaukee’s Fire and Police Commission in 2017 ordered Flynn to further loosen the policy, allowing pursuits in reckless driving cases, or when a car was linked to drug dealing. Pursuits in 2018 spiked to 940 from 369 the previous year. The number of pursuits ending in officer, suspect and/or third-party injury also swelled, with instances in each category more than tripling.

The public safety risk of pursuing those suspected of nonviolent crimes outweighs the risk from the violation itself, said Mark Priano, a board member with the advocacy nonprofit PursuitSAFETY. He lost his 15-year-old daughter in 2002 after a teenaged driver fleeing police ran a stop sign and struck the family’s minivan; she died a week later after slipping into a coma, according to media reports.

“These pursuit-related deaths or injuries are not accidents,” Priano said. “This was a planned event that could have been controlled.”

Safety advocates point to Milwaukee as an example of the consequences of rolling back a restrictive pursuit policy, said Geoffrey Alpert, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of South Carolina and an expert in high-risk police activities.

“Cops like to chase. It’s exciting. It’s a fun thing to do,” he said.

Alpert, who also sits on an advisory board for PursuitSAFETY, described the back-and-forth between Flynn and the Fire and Police Commission over pursuit policies and the ensuing surge in pursuit-related injuries as a “horror story.”

Pursuit reform often follows a cyclical pattern, Alpert said: more restrictive pursuit policies following injuries and deaths prove unpopular within police departments, prompting a return to the previous status quo.

Police call alternatives ‘practically impractical’

Companies are pitching to police a range of technologies aiming to reduce risky pursuits. They include high-tech GPS trackers, tire deflation tools and even a grappling device that might appear Batman-inspired — allowing an officer to entangle a fleeing vehicle to decelerate it.

Milwaukee police in 2016 started attaching GPS tags to certain cars, allowing for tracking in lieu of a pursuit, but that was later discontinued. Neither that nor other methods worked as well as traditional pursuits, the department says.

Before the Fire and Police Commission approved the latest version of Milwaukee’s pursuit policy last summer, one commissioner asked if alternatives existed to catch reckless drivers.

Nicholas DeSiato, the police department’s chief of staff, called nearly all alternatives “practically impractical.”

“They can be effective when appropriate, but it also requires incredible coordination and, sometimes, just dumb luck,” he said. “In terms of a hot pursuit, to effectively combat reckless driving, it’s a necessary tool.”

Priano of PursuitSAFETY acknowledged the need for police pursuits in certain situations. He advocates for restricting them to catch violent felony offenders — while finding other ways to deal with other reckless drivers.

As reckless driving persists, Sarnow doesn’t expect new restrictions on pursuits any time soon. But the department remains open to reviewing alternatives.

“We’d be remiss if we didn’t revisit these things, because things change right?” Sarnow said. “And we have to make sure that we’re staying on the forefront.”

Fewer pursuits in Madison

Madison, Wisconsin’s second largest city, has limited police pursuits as Milwaukee’s number surges. The Madison Police Department logged just 20 pursuits in 2022, about 2 percent of Milwaukee’s count, records show.

Madison has just under half of Milwaukee’s population and has logged no more than 27 annual police pursuits since 2016, even amid leadership changes and local reckless driving challenges.

Madison police use a stricter pursuit policy than Milwaukee’s: Officers may initiate pursuits only when they have probable cause that a suspect is committing, has just committed or is about to commit a felony — similar to Milwaukee’s former policy. A sergeant monitors the chase and can call it off. Additionally, officers must follow many traffic rules — including stopping at red lights and stop signs, Madison Police Chief Shon Barnes said.

The department also uses surveillance cameras and tire-deflating spike strips, Barnes said. If a suspect gets away, officers use detective work to locate them.

Barnes, who years ago as a rookie drove his police cruiser through a fence and hit a tree during a pursuit on a rainy day (he was uninjured), said his department’s safety-focused culture leads to fewer pursuits.

“Anyone who thinks a pursuit is out of policy or not safe — if you stop that pursuit, no one will say anything about that,” he said. “Because you’re ultimately responsible for what happens with that vehicle.”

Still, Barnes doesn’t fault Milwaukee for pursuing more cars under its looser policy, suggesting that comparing Madison to Milwaukee is not apples to oranges.

Milwaukee “may have more criminality, and we’re all dealing with the stolen car epidemic,” he said. “I think they’re trying to get a handle on it, just like we all are, and they’re doing what’s best for their community.”

‘I wish it was all a dream’

The judge presiding over Broomfield’s suit has put the trial on indefinite hold, as both her attorneys and the city’s attorneys finish preparations.

“There are police pursuits virtually every day of the week,” U.S. District Judge J.P. Stadtmueller said while presiding over a May pretrial hearing. “To suggest that each and every one of these cases exposes the officers to liability is very much an open question, at least in the mind of this judge.”

While Broomfield awaits the start of the trial, she’s trying to take care of her mental health, with regular trips to see a counselor. She is also getting support from her church congregation. Still, the pain persists.

“My husband ended up passing away from stress from a heart attack from just constantly being in pain and worrying about it,” she said. “My daughter, she’s not the same. She’s different. My son, he’s not the same. … Everybody is grieving.”

“Some days, I don’t even want to get out of bed,” she added. “Some days I just wake up and wish it all was a dream.”

Broomfield wants a more restrictive Milwaukee pursuit policy to prevent other families from feeling similar pain.

Her lawsuit isn’t about money, she said, and she also seeks accountability related to the pursuit that killed her son.

“I know everybody makes mistakes,” she said through tears. “Why couldn’t I even just get an apology that it happened to my child?”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

__________________________________________________________________________

What happens when a police pursuit crosses jurisdictional boundaries?

How should Wisconsin law enforcement coordinate when an officer chases a fleeing driver from one jurisdiction into another? The answer can be murky, but the scenario isn’t rare.

A 2018 USA Today Network-Wisconsin investigation found that Milwaukee’s since-loosened restrictions on police pursuits may have fueled police pursuits and reckless driving in surrounding suburbs as fleeing suspects kept driving across jurisdictional lines. Local police departments also share overlapping jurisdictions with sheriff’s offices and the Wisconsin State Patrol, which allows reckless driving pursuits.

Advocates of stricter police pursuit policies are split on whether state or federal lawmakers should standardize rules for all police departments. Wisconsin has broad “model advisory standards” but nothing binding.

Jonathan Farris, chief advocate for the Wisconsin-based Pursuit for Change was consulted when the Madison Police Department tightened its strict pursuit policy several years ago. He said standardizing rules would prevent confusion between departments.

“But I don’t see that happening,” he added. “Law enforcement doesn’t want it. And they’ve got a very powerful lobby, and they would lobby against that. Legislators don’t want to mess with that.”

Madison Police Chief Shon Barnes opposes the idea.

“I think local control is better,” he said. “I’m paid by the citizens and taxpayers in Madison, so I have to police and work the way they want. The state government, unless it’s a safety issue, really shouldn’t be intervening in that — and I don’t think they want to as well.”