This story was originally published by Wisconsin Watch. It includes references to sexual assault of a minor and mental health issues.

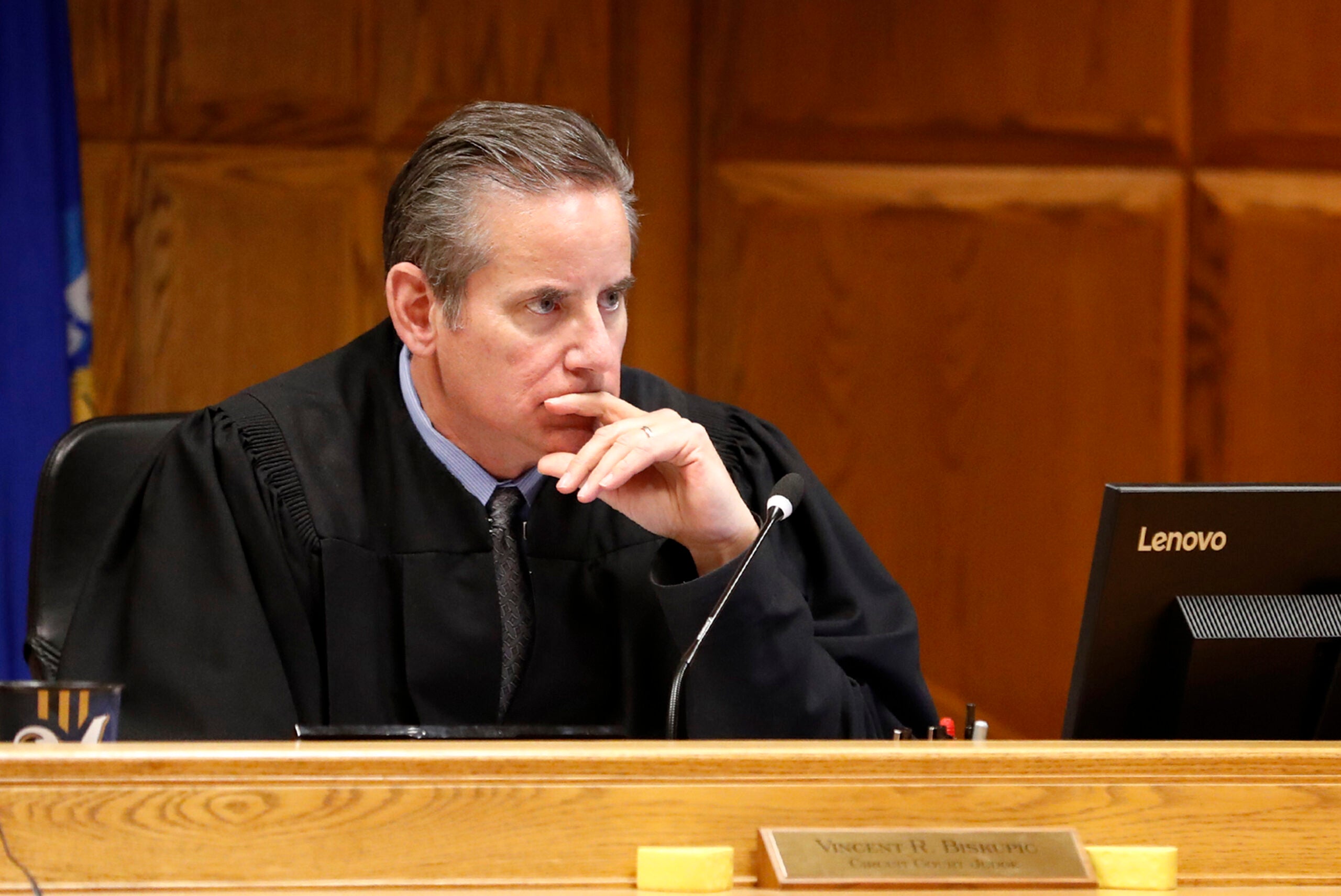

Last March, Outagamie County Judge Vincent Biskupic ordered a man convicted of sexually assaulting a minor to pay $150,000 in restitution to the county to reimburse for mental health services, even though the county said it didn’t want to request any money in part because seeking it could “revictimize the victim.”

Eight months after sentencing, the victim died unexpectedly. She had just turned 18.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Her case got further than the vast majority do. According to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, just 31 percent of sexual assaults are reported, 5 percent of perpetrators are arrested and just 2.8 percent of cases end in felony convictions.

But the process proved painful. Assistant District Attorney Julie DuQuaine told the judge the teenager’s mental health plummeted after trial, saying she suffered “complete deconstruction.”

About a month after trial, as part of sentencing, which included eight years in prison and 12 years of extended supervision, Biskupic had to decide how much, if any, restitution the perpetrator, Patrick Tully, should pay.

Restitution is supposed to make a crime victim “whole.” The victim or prosecutor could have asked for restitution in the case, but neither did. Instead, Biskupic ordered the $150,000 restitution — a huge amount for any offender — be paid to the county during sentencing, even after the county initially declined to request any amount.

A law professor, a former Supreme Court justice and an attorney who litigates crime victim’s rights issues reviewed court records at Wisconsin Watch’s request, and the State Public Defender’s Office reviewed the circumstances. They described Biskupic’s approach to restitution as “unusual,” “odd” and even “improper.”

“This judge seems to be a very activist judge,” said John Gross, a clinical law professor at the University of Wisconsin Law School. “He seems to want to insert himself into the resolution of cases in ways that are often not appropriate, or at the very least, not authorized by any statute.”

Gross also raised concerns the restitution order, which directed money to the county that supported the victim after the assault, could set a dangerous precedent in which judges or district attorneys could use restitution to fill government coffers.

Biskupic declined an interview through his judicial assistant, saying the case is ongoing. The deputy corporation counsel also declined, and DuQuaine did not return a request for comment.

Not taking no for an answer

Although state law requires judges to order restitution, barring “substantial reason not to do so,” the prosecutor bears responsibility for documenting losses resulting from a crime.

Through court orders, Biskupic twice prompted DuQuaine to submit information that might inform a restitution request, later specifying she should work “directly with the county human services office and corporation counsel office” to determine amounts.

The county’s deputy corporation counsel, Dawn Shaha, declined to “request restitution for the County” in a letter, writing: “It would not be feasible for the County to parse out specific amounts directly attributed to this assault, and we believe submitting an arbitrary amount could ultimately end up revictimizing the victim in this case.”

Although Shaha said by phone she would consider questions sent via email, she ultimately declined.

Outagamie County Health and Human Services Director John Rathman told Wisconsin Watch in a written response to questions that the judge’s request was not “routine.”

Gross, former Supreme Court Justice Janine Geske and Legal Action of Wisconsin attorney Patrick Shirley all said Biskupic’s restitution inquiry should have stopped when the county declined to request it.

“They might be entitled (to restitution), but they are waiving it and saying, ‘We don’t want it,’” Geske said. “I question whether a judge ought to be ordering restitution to somebody who says they don’t want it.”

But records show Biskupic did not take no for an answer, ordering Shaha to determine how much money the county had spent on the survivor’s care at private facilities since her assault, even after Shaha voiced her aversion in open court.

Transcripts show he even directed the prosecution to call in a social worker to testify, whom he then questioned directly.

At the hearing, Biskupic said his inquiry did not seek “the benefit of one side or the other,” saying that Tully’s sentence might benefit if the survivor were “doing well and stable.” But if she had struggled, requiring hospitalization, then the prosecution’s failure to provide that information “creates a void that I think is contrary to the victims’ rights law.”

“There’s a legitimate inquiry to be made by a judge about potential restitution that they should order under the statute,” Gross said. “But then there’s inserting yourself into the adversarial process to a degree where you seem to be advocating for one side.”

Biskupic’s backstory

Biskupic’s judicial practices have attracted scrutiny before.

In 2021, Wisconsin Watch and WPR exposed his tendency to stretch the conventional bounds of sentencing authority by crafting arrangements not spelled out in state law, such as his own form of probation separate from the Department of Corrections. About two dozen legal experts had varying opinions on its propriety, alternatively describing it as legal, a gray area and unauthorized.

The revelations came during the reporting for “Open and Shut,” a seven-part investigative podcast series that scrutinized Biskupic’s record as Outagamie County district attorney.

The series showed Biskupic using his broad discretion to push boundaries as a judge and prosecutor, as far back as the 1990s.

A review of Outagamie County circuit court data over the past five years shows defendants seek to substitute Biskupic for a different judge at a rate only second to Judge Mark McGinnis, whom Wisconsin Watch has reported also has a record of overreaching his authority.

Violating her privacy

Shirley said the judge’s insistence on determining restitution intruded upon the survivor’s privacy.

“Victim privacy, especially in the context of mental health, is really important,” Shirley said. That’s because sexual assault entails a “loss of agency,” and many of his clients have felt “re-victimized by a process that exposes their mental health records or details of their mental health struggles.”

Biskupic instructed the prosecutor to retrieve records about the survivor’s wellbeing from a separate, juvenile case and referenced it again at the hearing.

“It’s odd that the court’s doing this, and it raises some red flags to me that this isn’t coming from the victim herself,” Shirley said. “I feel like she should have input in that both intuitively and legally.”

On the first day of sentencing, which the survivor did not attend, the prosecutor said that while she had contacted the survivor’s social worker, asking her to share information “if there’s anything (the survivor) wants us to know,” she had received nothing back. The survivor “did not want to share it, or she didn’t have any information to share,” DuQuaine said.

The survivor attended the second day of sentencing, but she did not wish to speak.

“Often, people with very good intentions, who want to see (survivors) protected, can end up being, shall we say, paternalistic,” Shirley said. “People that are trying to do good things for them and protect them and look out for them end up cutting off their agency.”

To the county, not the victim

In Wisconsin, bond money posted by a person convicted of a felony gets applied to restitution and payments of the judgment. Tully’s father, Andy Tully, said in an interview he posted a total of $250,000 in bond on his son’s behalf, confirmed by court documents, and he had anticipated recouping it if his son complied with all conditions. If the judge had stopped his restitution inquiry after the county declined to request it, Tully’s father might have gotten more back.

Instead, Biskupic ordered Tully to pay $10,000 toward the survivor’s future therapy costs, citing a statute that allows for additional restitution up to that amount for “necessary … psychiatric and psychological care and treatment” in “sexually motivated” crimes.

He also ordered Tully to pay $150,000 to Outagamie County to reimburse for “past payments” it made on the survivor’s behalf for “counseling and treatment” at private contracted facilities following the assault. The county estimated her treatment so far had cost more than $252,000 and that future treatment could exceed $100,000.

“This is a huge amount of restitution,” Geske said — a sentiment echoed by Gross and Shirley. Data on restitution figures in sexual assault cases was not readily available, but Gross noted the figure exceeds the maximum fine allowed for the crime by $50,000.

Rathman, the county human services director, said it was possibly the first court order he had seen requiring repayment for county services rendered to a victim.

The attorneys consulted by Wisconsin Watch had varying opinions on its propriety. Geske said the case law Biskupic cited in the hearing and orders supported his actions, noting judges have broad discretion. Shirley and the State Public Defender’s Office said it fell into a gray area. Gross considered it unauthorized.

“This is a really slippery slope to go down,” Gross added. “The last thing we want to do is have a precedent out there where courts can just pile on hundreds of thousands of dollars of debt in the guise of it being restitution for people who are already being convicted of crimes.”

Wisconsin prisons pay incarcerated people pennies an hour for their labor. After they leave prison, it becomes harder to find a job, and they may remain on probation longer due to inability to pay high restitution costs.

An appellate court could determine whether Biskupic’s ruling fell within the bounds of the law, but Tully has not appealed. Records show Biskupic scheduled a hearing to determine whether funds from the $10,000 amount should be disbursed for any therapy accessed after sentencing. The prosecutor informed the court the victim had died. A hearing is set for Jan. 22.

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.