People lie. But their blood and fingernails do not.

Wisconsin has a drunken driving problem: More than one-third of the people convicted of operating while intoxicated have been convicted before, according to data analyzed by Gannett Wisconsin Media for its Under the Influence project with the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

To find out which offenders are at risk of driving drunk again, and help them avoid it, the state requires drivers to undergo a drug and alcohol abuse assessment. Essentially, trained professionals ask drivers about their drug and alcohol use.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

But the answers are unreliable. And alcohol is a pesky little molecule to detect because it fades so quickly from the body. The standard blood test only works for a few hours.

In the past several years, a handful of Wisconsin counties became the first nationwide to try a solution European nations have been using for years. They are testing repeat drunken drivers for molecular evidence of heavy drinking in nail or blood samples. Known as alcohol biomarkers, these tests can look back weeks or even months.

Researchers say their initial data show that biomarker testing during treatment may help repeat offenders stay sober longer, keep them from getting rearrested, and ultimately save counties money.

Most approaches to Wisconsin’s repeat drunken drivers have been about “increasing fees, or increasing jail time,” said Pamela Bean, the researcher who initiated the programs and is evaluating them. “This is a different approach.”

“The goal is not to catch people. It’s to get them sober, so that they’re not killing someone on the road, and that they actually discover that there’s another life out there,” said Doug Lewis, president and scientific director of U.S. Drug Testing Laboratories Inc. in Des Plaines, Ill., which is analyzing nail and blood samples from several Wisconsin counties.

In Dane and Waukesha counties, among the first to try the testing, Bean has found that drivers who tested positive during their year of monitoring were more likely to be rearrested. If biomarker positives turn out to be a red flag for recidivism, counties can target those drivers for extra treatment interventions.

In Waukesha, drivers under biomarker monitoring were re-arrested on average a year later than drivers who were not monitored.

Bean and Lewis believe more counties and states will be interested in biomarker testing if it is successful. But they say it is too soon to declare that.

“This is all data-driven, it’s all new,” Lewis said. “This is data no one else has really seen before.”

Biomarker expert Paul Marques, senior research scientist at Pacific Institute for Research and Evaluation in Maryland, said, “If you need to know what somebody’s drinking level is and whether it’s a public hazard, you need to use something that can get you objective information.”

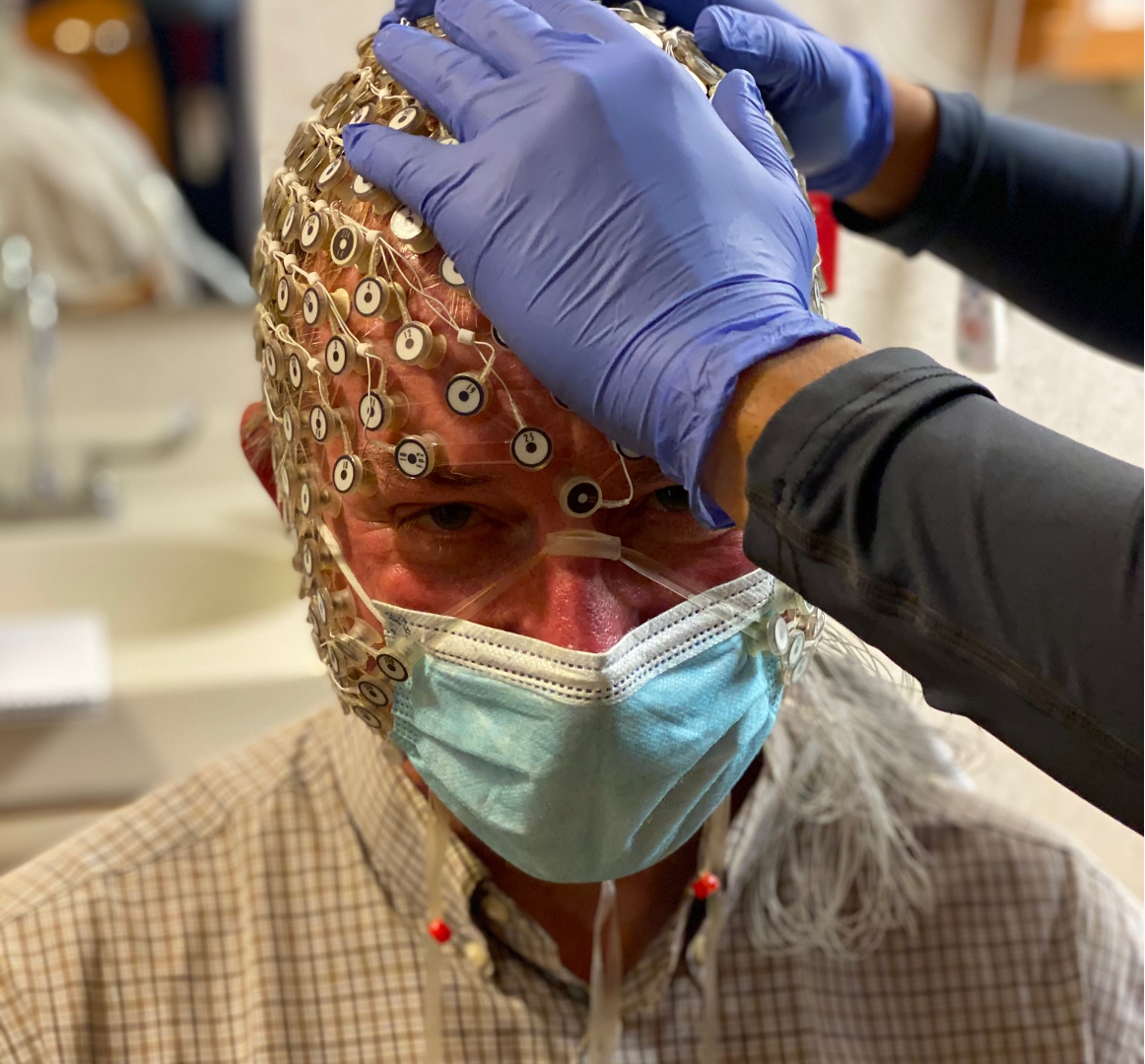

Doug Lewis, president and scientific director of U.S. Drug Testing Laboratories, demonstrates one of the advantages of using nail samples for alcohol and drug biomarkers: collection is a snap. The hard part is the analysis, which requires a tall machine that costs $500,000. Photo: Kate Golden/WCIJ.

Marques is an advocate for using the tests, which provide a look back in time and assist with treatment, in conjunction with ignition interlocks, which prevent drunk people from driving in the moment.

“I look forward to a day when some state has the moxie to do a three-legged program: interlock, alcohol biomarker monitoring, and treatment for those who cannot change behavior on their own,” he said.

Bean moved to Wisconsin 17 years ago from California, where she had been working with alcohol biomarkers. She was appalled by a report showing one in three Wisconsin drivers admitted to driving under the influence, and by the frequency of repeat operating-while-intoxicated convictions.

“Every time I would see in the newspaper, it was like, this person has been convicted by seventh OWI, eighth, 11, 13! I never saw that anywhere,” she said. “Then I said well, why are we not doing here the same thing that European countries are doing?”

In late 2005, she gave a presentation on alcohol biomarkers to a statewide advisory committee looking at new approaches for intoxicated drivers. After the meeting, the state wrote a letter to all 72 counties saying that this new approach was available and permissible under state law. Six counties were interested.

Waukesha County was first to try it in 2006. Dane followed in 2010, with some startup funding rounded up by former county executive Kathleen Falk.

Kenosha came on board, adding a suite of tests for different drugs as well — the law forbids operating “while intoxicated,” which can include other drugs in addition to alcohol. Forest, Vilas and Oneida counties got a grant to test for alcohol biomarkers and are looking at testing for drugs.

It works like this. A driver, generally with at least three OWI convictions, walks in for the mandatory alcohol and drug abuse assessment, part of a driver safety program required by the state. The assessor will ask the person about his or her substance use, recommend a treatment program, and initiate biomarker testing.

The first test is used as a baseline. It tells the assessor whether the driver told the truth — and can admit it, according to Lewis.

“The therapist has an enormous history now to break the denial. And that’s what probably is the biggest resistance to treating someone who has a chronic relapsing disease,” Lewis said.

The answer also may prompt the assessor to call the driver’s treatment provider and suggest fine-tuning the plan.

The next test comes near the end of treatment, to see if it is working. A driver who tests positive at that point has to come back for more testing the next month.

After several months of treatment are up, drivers usually have a gap of several months or a half-year before the driver safety plan ends. That is when data show a person is most at risk of relapsing, Bean said.

So drivers are required to submit one final test a month before the driver safety plan is up.

The tests seem to serve as a deterrent, Bean said. Waukesha and Dane drivers who tested positive then got a two-minute intervention call giving them the results, suggesting they strengthen their support networks and telling them they would be retested — and 60 to 80 percent of them tested negative the next time around.

Cesar is a hotel worker with five OWI convictions. He asked not to be fully identified to avoid embarrassing his employer.

At a recent interview, he said he would have his final biomarker test the next day.

Researcher Pamela Bean started alcohol biomarker pilot projects in several Wisconsin counties after moving here from California. “Every time I would see in the newspaper, it was like, this person has been convicted by seventh OWI, eighth, 11, 13! I never saw that anywhere,” she said. Photo: Kate Golden/WCIJ.

He hoped it would show that he has been sober for two years. He has something to prove, not just to the judge but to his family.

“That I’m not a bad person,” he said. “So that way, I can get my driver’s license and get back to my normal life, like everybody else.”

In Dane County, Journey Mental Health Center conducts driver assessments. Assessor Kevin McConeghey said Cesar’s desire for proof is part of why biomarker tests are helpful. These are people who have tried quitting before. People in their lives have a tendency not to believe them.

“What this does is it reinforces the natural pride that a person would have in being sober. And it allows them to take a little more ownership of what they’re doing to stay sober,” McConeghey said.

Dane and Waukesha are testing for what are known as indirect markers.

Their program, called EDAC, is a suite of 20 routine blood tests, for instance cholesterol and liver enzymes. The results are statistically analyzed for the likelihood that a person was heavily drinking in the past month.

They are not perfect; there is a small chance that other conditions can cause the same test results. But they have an advantage: They show the damage that alcohol has done to a person’s body.

If the liver enzyme comes back high, for example, the client can learn “right away that their drinking is having an effect on their liver,” McConeghey said. “And a lot of studies show that immediate feedback about health effects of drinking have a significant effect as long as five years later on the client’s drinking.”

The fingernail and blood-spot tests used in Kenosha, Forest, Vilas and Oneida counties do not provide that kind of information. Those tests are looking for so-called direct biomarkers, which are the byproducts of alcohol itself.

Among their advantages is that they are easy to collect, requiring just a clipping.

They can be used as forensic evidence in court, because only alcohol can create their signature results. And the samples can also be used to find other drugs, as Kenosha County is doing. Wisconsin’s heroin epidemic has prompted extra interest in testing for other drugs, Bean said.

But for all the markers being used, there are costs.

At U.S. Drug Testing Labs, which analyzes samples for Kenosha, Forest, Vilas and Oneida counties, Doug Lewis walked a reporter through the analysis.

Clipping nails may be easy, but finding alcohol in them requires a tall machine that costs a half a million dollars.

It is called a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer, “and it’s one of the more sensitive instruments that you can buy in the analytical chemistry world,” Lewis said.

Drivers pay about $100 for each test, and they need at least three — so many counties are hesitant to lay such costs on people who are rarely flush.

Bean is trying to get the costs down. But she says even at $300 for a three-test regimen, the tests will save counties money if they keep people out of prison.

“In one year, it’s $30,000. So you do the math. It’s 100-fold less expensive to test this person with biomarkers than to put him in jail.”

Andrew MacGillis is serving time at Fox Lake Correctional Institution for his seventh drunken driving offense. He believes he has changed his ways — and says he would be happy to pay to prove it. He’s corresponded with Bean, who has come to visit him.

“That’s pretty cheap for an inmate to pay for that,” MacGillis said. “Yeah, I would definitely want to be in the program.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. This report was prepared in collaboration with Gannett Wisconsin Media for its “Under the Influence” series. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.