On its first day of oral arguments since liberals took control of the Wisconsin Supreme Court, justices questioned whether a charitable arm of the Catholic Diocese of Superior should be exempt from paying into Wisconsin’s unemployment insurance system.

Catholic Charities Bureau, Inc. argues its social welfare programs throughout Wisconsin are operated primarily for religious purposes and should be exempted from state unemployment insurance payments. In 2015, a Douglas County Circuit court judge exempted Challenge Center, Inc., a Catholic Charities subsidiary helping people with developmental disabilities, from having to pay into the state plan.

The Catholic Charities Bureau, or CCB, argues its other subsidiaries should also receive an exemption allowing them to pay into a church-run unemployment program. A circuit court agreed in 2020.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Two years later, a state appeals court overturned the rulingand sided with the Wisconsin Labor and Industry Review Commission, which argues while the diocese operates the CCB, the activities it performs — including offering low-income housing, assistance for the elderly and disability services — aren’t expressly religious in nature.

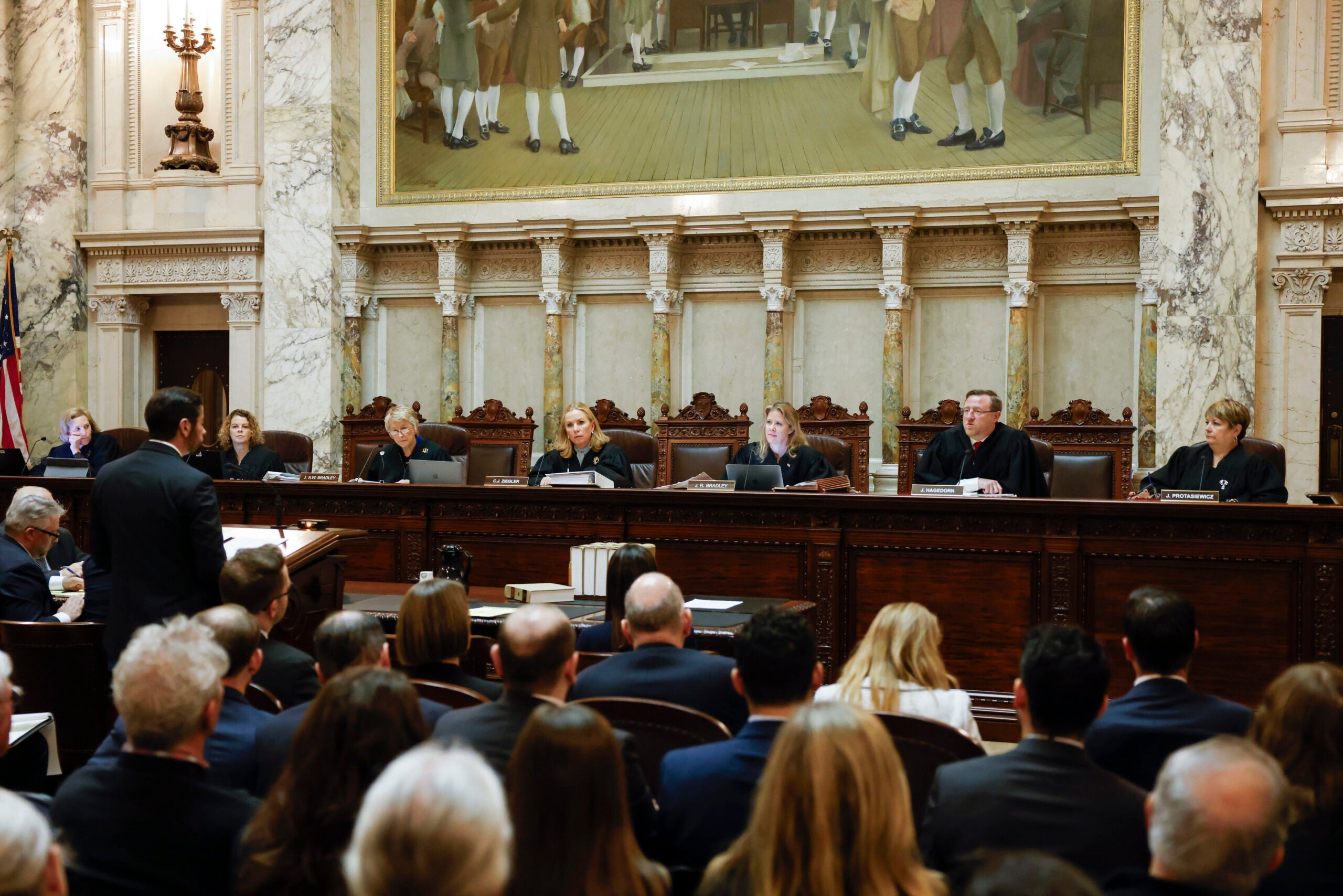

During the first day of oral arguments before the court — operating under a liberal majority for the first time in 15 years — justices took different approaches when questioning attorneys representing the Catholic Charities Bureau and state.

Liberal Justice Rebecca Dallet questioned where to draw the line for exempting charities run by religious organizations when “all you have to do is say a religious purpose, which is pretty broad stuff.”

“I mean, these are some pretty broad principles which are the basis of, I would venture to say, most religions, maybe all religions,” Dallet said. “So, where is that line?”

Attorney Eric Rassbach, of the Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, which is representing the Catholic Charities Bureau, told the court the sincerity of the church’s mission to help the underserved is one limiting principle.

Dallet asked, “If someone says it’s their religious belief, what court can question that?”

Rassbach said courts “decide sincerity questions all the time” with regard to religious claims. He also said a nonprofit having an affinity for a religion isn’t enough.

“It actually has to be something that is operated by or controlled by a church,” Rassbach said. “And in this case, the diocese is the church. And so therefore, I think those are some pretty important limiting principles.”

Attorney Jeffrey Shampo, representing the Wisconsin Labor and Industry Review Commission, told the court that while the Catholic Charities Bureau is run by the diocese, federal tax forms and websites from its various nonprofits don’t mention religious activity. He said state statute requires nonprofits to be primarily operated for religious purposes in order to qualify for an unemployment insurance exemption.

“We have to look at the activities that they do, because otherwise they can assert that anything they do through these organizations would have a religious purpose because they’re all nonprofits,” Shampo said.

Conservative Justice Rebecca Grassl Bradley disagreed.

“Your test would violate Catholic doctrine because Catholic doctrine says the provision of charity must be to all people, not discriminating against people based on faith,” Bradley said. “Charity should be provided to people who have no faith without proselytizing. So again, doesn’t your test, as you’ve advanced it, discriminate against religions that don’t look like what the Court of Appeals of Wisconsin apparently regards as religion?”

Conservative Justice Brian Hagedorn, who has been a swing vote on the court in the past, said he understands that any of the nonprofit subsidiaries in the case are “going to be operated by an organization that has religious purposes at its core. But that’s not enough to qualify.”

“Just looking at the statute,” he continued, “it seems to indicate that that’s not enough, that if you’re operated by an organization with a religious mission, that that’s not enough by itself. It also needs to be operated primarily for religious purposes on its own.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.