A man who was wrongfully convicted of a crime for which he served 10 years in prison and was later exonerated, is returning to Wisconsin as an attorney, inspired to change the stigmas surrounding the state’s incarcerated populations.

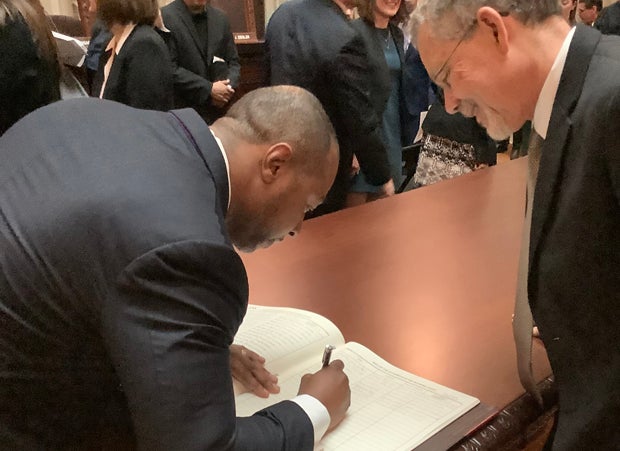

On Wednesday, Jarrett Adams was admitted to the Wisconsin State Bar in a ceremony at the Wisconsin State Capitol. Joining Adams was Keith Findley, co-founder of and now senior advisor to the Wisconsin Innocence Project, in which legal experts lead University of Wisconsin-Madison law students in efforts to overturn wrongful convictions.

“It was a moment that I most certainly wanted to share with him, as well,” Adams said about being sworn in by Findley, who argued Adams’ case and helped in overturning his conviction.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

After his exoneration, Adams attended Loyola University Chicago School of Law where he earned a law degree. He was initially admitted to the New York State Bar four years ago, after which he served on the Innocence Project there.

Adams was wrongfully convicted of sexual assault when he was 17 years old. He was given a 28-year sentence at a maximum security prison and ended up serving about 10 years of that sentence before being exonerated in 2007.

He said that his experience with the justice system was evidence of the impact that having a low income has on a person’s chances of getting incarcerated.

“Guilt or innocence shouldn’t be decided on how much you can afford,” he said. “In my case, it most certainly was.”

Adams explained he was given a panel attorney, which is someone appointed to handle cases that public defenders offices can’t take, for example due to conflicts of interest. Panel attorneys also have agreements with the courts to handle cases where the defendants can’t afford an attorney.

“I didn’t get a great attorney and it had a direct bearing on the outcome of my case,” he said.

According to the Innocence Project, perjury or false accusations are contributing factors in nearly 60 percent of the 1,861 recorded exonerations across the nation. The Innocence Project lists this and inadequate legal defense as factors leading to Adams’ incarceration.

Adams said being incarcerated put him in an environment where he heard stories from other men and came to realize that “the person isn’t born at the point of their accusation.” He said it became clear that for many men, their stories started in the communities where they lived, where they were impacted by stressors that they never got a chance to heal from. In some cases, that led to mental health issues such as post-traumatic stress disorder that remained unaddressed.

Adams said he was interested in returning to Wisconsin, particularly because of the state’s bloated prison population.

“I really want to live a life as an example of what can happen when people are given the opportunities and the tools to reintegrate successfully back into our society,” he said. “We can’t repair what is going on in our impoverished areas in the state of Wisconsin by locking everyone up.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.