It’s not uncommon for Betty Sacia’s phone to ring at all hours of the day. In fact, she often tells people she works 24/7.

“I’ll get a phone call on Sunday at 5 o’clock in the afternoon, and I think, ‘Now, what clerk works on Sunday at 5 in the afternoon?’” Sacia says laughing. “I think people out here are just used to that now. ‘Oh, I’ll just call her, she’ll be there.’”

Sacia is the Town of Farmington clerk, one of 1,852 municipal clerks in Wisconsin. It’s a position responsible for, among many other things, running the state’s elections.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

And unlike the state’s larger cities and villages, Sacia runs Farmington’s elections by herself, even though she’s technically part-time.

Town of Farmington Town Hall. Photo courtesy of Betty Sacia

The Town of Farmington, about 25 miles northeast of La Crosse, is home to about 1,180 registered voters. It’s Sacia’s job to make sure they have all the information they need — from how to register, to where and when they can cast an absentee ballot, to where they can find their polling place. She also recruits and schedules the poll workers that help her manage election day tasks.

Sacia works out of an office at her home, but during peak election season she schedules regular office hours at the town hall, so people can register and vote in-person absentee.

Up until a few years ago, the time constraints of her full-time job at Gundersen Medical Foundation forced her to handle all of her clerk duties from home. She welcomed Town of Farmington residents into her house, where absentee voters would cast their ballots at her dining room table.

Kevin Kennedy directed Wisconsin’s statewide elections agencies for decades. Photo courtesy of Kevin Kennedy

Kevin Kennedy, who ran Wisconsin’s statewide elections agencies for decades, says the practice of “kitchen-table voting” isn’t uncommon in Wisconsin — where more than 60 percent of clerks work part-time.

“Some (clerks) have offices in the town hall, but many times the town hall is not heated and is only used once a month for town board meetings and for elections,” Kennedy said. “So, they often work from their home … It’s not unusual that you’ll go to the town clerk’s home to cast an absentee ballot right before the election.”

For Sacia, it’s all about being flexible.

“I just arrange to make sure that I’m available for people,” Sacia said. “I don’t want anyone to ever say they weren’t able to vote, and it was my fault. That would be awful.“

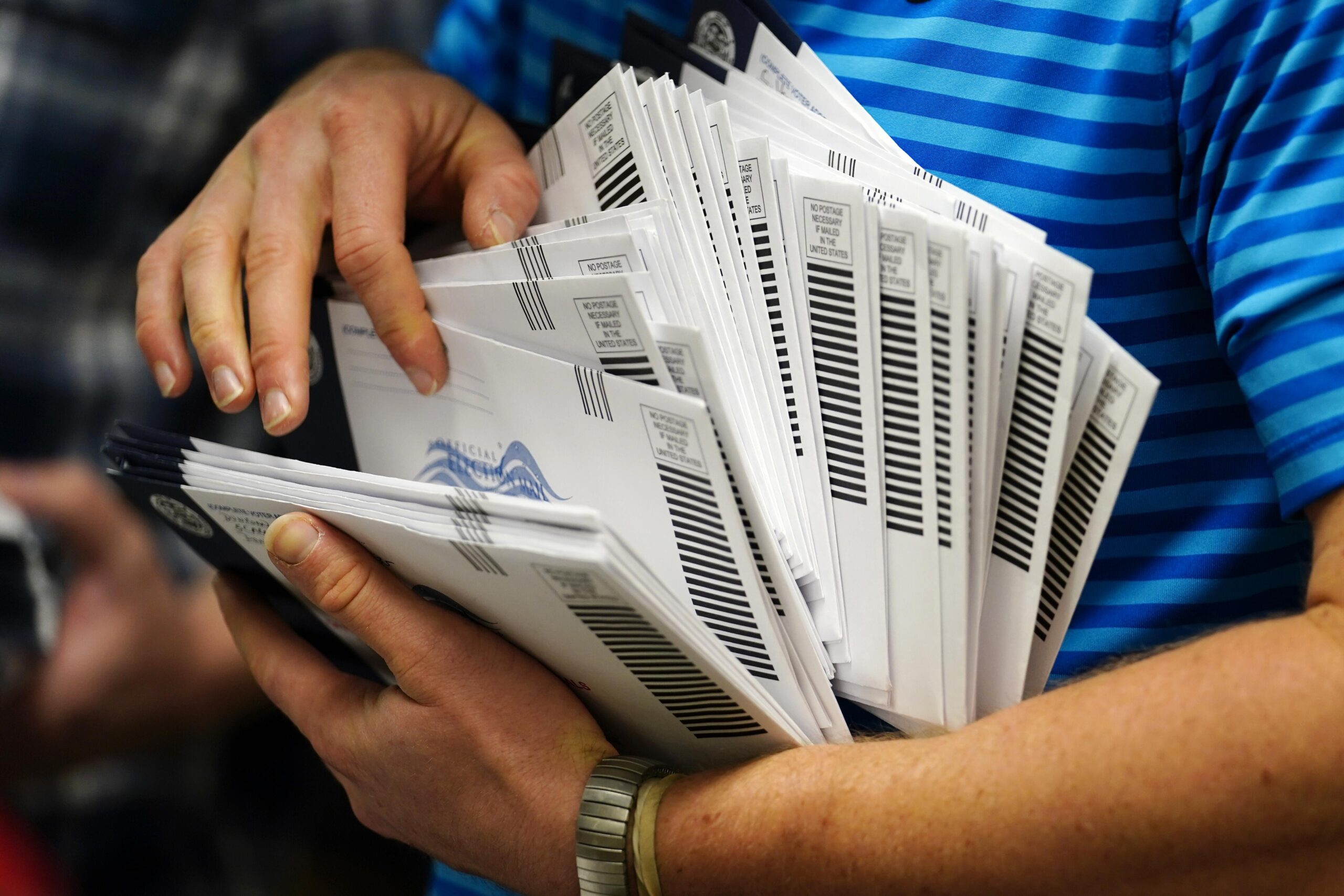

As for the ballots themselves, they are always collected the same way — whether it’s at the town hall or at her dining room table.

“It works just like when you come to vote,” Sacia said. “All those ballots are kept securely until the election day when I open those envelopes and put them into the tabulator.”

It’s a voter experience that’s unique to Wisconsin’s rural communities, Kennedy said.

“Wisconsin is based on local government and it’s very informal, it’s closer to the voters, and that makes it more personable, but it also could make it more vulnerable because you don’t have a lot of the institutional safeguards that you might have in a city,” Kennedy said.

At a time when election security is at the top of people’s minds, Wisconsin election officials say they’re doing everything they can to ensure the voting process is secure — whether it’s a small town like Sacia’s or a major metropolitan area like Madison or Milwaukee.

Keeping Elections Secure

On Sept. 22, 2017 Wisconsin was notified it was one of 21 states targeted by Russian hackers before the 2016 presidential election.

While the attempts were unsuccessful, the threat has led to increased scrutiny on the voting process across the state.

Reid Magney, spokesman for the Wisconsin Elections Commission, said the agency has been homing in on making every part of the process more secure, from new training videos to instituting new security procedures for WisVote, the election management system clerks across the state use to run elections.

“We have six different videos that (clerks) have to watch that deal with online security, avoiding phishing scams, and what are good password policies to have, all of that kind of stuff to essentially protect the system,” Magney said.

For clerks, that means they still need to enter a username and password to access voter data, but they also have to use an electronic “key” attached to a USB drive. That makes the system even harder to hack.

These steps are all part of a process to make Wisconsin’s election process the same from county to county.

“Elections are supposed to be uniform across the state,” Magney said. “That a person who’s going into vote in Milwaukee has essentially the same experience as someone who’s going to vote in a small town up in Sawyer County … while obviously the polling places are going to be different, the way that you’re treated at the polling place — the procedures — are all supposed to be uniform.”

But it wasn’t until 2002 that much of the state — and country — adopted a uniform system.

Sophisticating The System

In 2002, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act, a law that would make major changes to the nation’s voting process. One of which included the creation and upkeep of a statewide voter registration database.

Before the law was passed, Kennedy explained, about 1,500 of Wisconsin’s municipalities weren’t required to have voter registration.

“If your population was under 5,000, you just showed up at the polling place, gave your name and address,” he said, adding that “it used to be that they could pretty much run an election out of a shoebox, they sort of knew in their head who their poll workers were, had an idea of who was gone for the winter, who may have passed away.”

But the implementation of the Help America Vote Act completely changed how the state’s clerks did their jobs.

“Some of the small-town clerks went from someone who basically kept a big book with a list of names of voters and gave them ballots when they came in … to having to comply with a whole bunch of different security procedures,” Magney said. “So, the job has changed radically in the last decade.”

Marilyn K. Bhend welcomes the changes. She has served as clerk of the Town of Johnson in Marathon County since 1991.

“When I first started, we didn’t even have a poll list that we had to go in, people would just come in and give their name and address and they would get to vote!” she exclaimed. “It’s been a progression of what we had to do.”

Town of Johnson Town Hall in Marathon County. Photo by Marilyn Bhend

But while technology has streamlined the voting process, Bhend says the job of clerk has become more strenuous since she began nearly three decades ago.

“Elections (are) taking more and more time, especially this year where there are four elections, and the responsibility of going through, making sure that your certified, that you get the six hours of training every two years, that you keep up on what the changes are, but there is places that you can get help,” she said, referencing her county clerk, the Wisconsin Towns Association and the Elections Commission. “But clerks do a good job in the rural area because we care and we’re dedicated.”

Marilyn Bhend, Town of Johnson clerk. Photo courtesy of Marilyn Bhend

Like Sacia, Bhend also works from her home, though she travels to the nearby town hall when voters want to vote in-person absentee.

Bhend says the Town of Johnson, roughly 30 miles west of Wausau, has about 375 registered voters. She expects to process about 15 absentee ballots.

As of Oct. 22, Sacia of the Town of Farmington had processed 36 absentee ballots.

On a much larger scale, as of Oct. 26, the Elections Commission reported Wisconsin’s clerks had issued nearly 327,000 absentee ballots, and 258,695 had been returned statewide.

Regardless of where those absentee ballots were cast — whether in the mail, at a local town tall, or at their clerk’s kitchen table — the process was the same.

“The beauty of rural government is that your municipal officials are your friends, your neighbors, your family,” Kennedy said. “While we have more challenges when we have 1,852 municipal clerks and 72 county clerks in terms of coordination, we also have a personal contact that is so essential. Because when it comes down to it, that’s what’s happening, individuals are choosing other individuals to be their elected representatives and so it’s a very person-driven system.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated at 11 a.m. Tuesday, Oct. 30, 2018 to clarify that poll workers also aid in running elections.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.