A decade ago, a blue-green algae bloom had never been reported on Lake Superior. Now, half a dozen blue-green algae blooms have been reported this summer across Lake Superior, including one that formed recently in Superior. But researchers say the blooms were relatively minor.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources is aware of six blooms reported across the lake with five observed during the month of July and one that occurred on Sept. 10, at the Barker’s Island beach area in Superior.

“In general in Lake Superior, the conditions where you would typically see blooms occurring in the lake would be if you had really calm conditions,” said Gina LaLiberte, the DNR’s harmful algal blooms coordinator. “So, any cyanobacteria, or blue-green algae, in that lake water can then float to the surface, and it can be accumulated near shores if wind is blowing towards shore.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

LaLiberte noted the bloom observed in the Barker’s Island beach area formed in a more protected spot, creating calm conditions that allow blue-green algae to build up.

The Thunder Bay District Health Unit reported the lake’s first bloom on July 9 in Black Bay within the Canadian province of Ontario. Nearly a week later, University of Minnesota-Duluth scientists, the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and a National Park Service ranger observed four blooms in and around Duluth and within the Apostle Islands sea caves during the weekend of July 17-19.

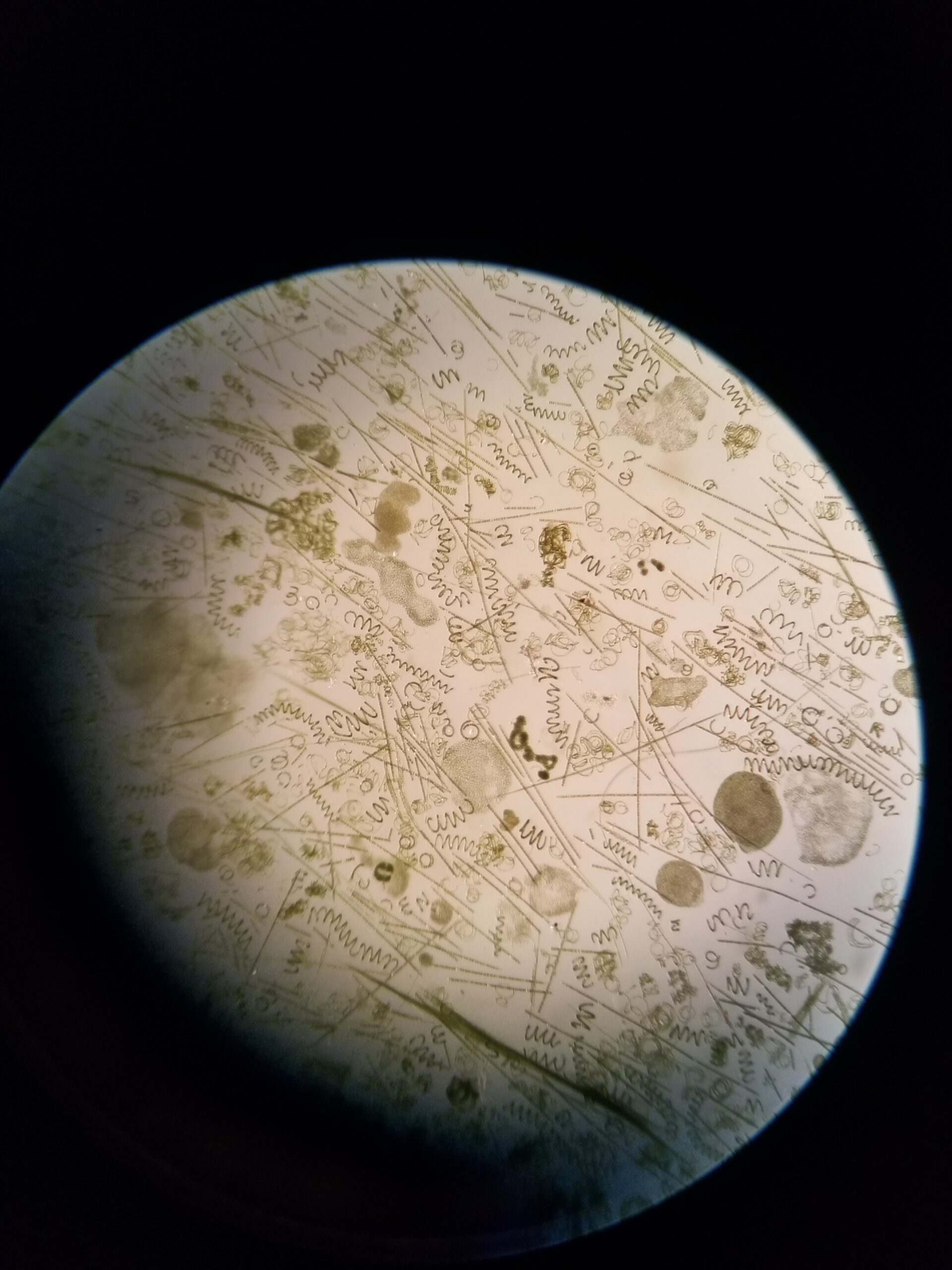

Blue-green algae often looks like pea soup or spilled paint as it collects near the shore. The scum can produce toxins that can make people or animals sick. LaLiberte said state health officials haven’t received any definitive reports of illnesses linked to blooms on the lake this year.

The public has reported around 160 blooms statewide this year — not all of which were blue-green algae.

Photo courtesy of Hannah Ramage with the Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve

The first blue-green algae bloom on Lake Superior was reported in 2012 following storms that caused massive flooding in the region. Another large bloom formed in 2018 that spanned along the lake’s south shore from Duluth-Superior toward Ashland.

The blooms reported this year have been short-lived and relatively minor by comparison. Staff at the Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve, or NERR, in Superior spotted the bloom at Barker’s Island on Sept. 10, according to Deanna Erickson, director of the Lake Superior NERR. By that afternoon, the thick scum had already dispersed.

Erickson said it’s the third blue-green algae bloom they’ve seen at Barker’s Island in the last couple of years.

“They have not had toxins associated with them so far here,” said Erickson. “And that’s an interesting question. Why don’t they? Or, what would make them have toxins associated with them?”

Photo courtesy of Hannah Ramage with the Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve

Researchers and scientists with multiple agencies have been on the lookout for blooms as part of monitoring efforts to determine what factors present ideal conditions for them to form, including Robert Sterner, director of the Large Lakes Observatory at the University of Minnesota-Duluth. His lab is one of the first to investigate blooms when they’re reported.

Sterner said several types of blue-green algae were observed in the bloom at Barker’s Island.

“That actually makes it a little bit unusual for Lake Superior because previous blooms, almost every event has been dominated by a single type of blue-green algae or cyanobacteria,” said Sterner.

The scientific name for what researchers typically see in the lake is a type of cyanobacteria known as Dolichospermum, which was detected in the Apostle Islands bloom. But the bloom at Barker’s Island included other types of blue-green algae, including Microcystis. Sterner said a biodiverse bloom creates more opportunities for different kinds of toxins in the water.

“We have yet to see a Lake Superior bloom or any of the usual blue-green toxins, which are problematic worldwide,” said Sterner.

[[{“fid”:”1577341″,”view_mode”:”full_width”,”fields”:{“alt”:”blue-green algae”,”title”:”blue-green algae”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-landscape”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EBlue-green%20algae%20observed%20at%20the%20Barker’s%20Island%20beach%20area%20in%20Superior%20on%20Friday%2C%20Sept.%2010%2C%202021.%3Cbr%20%2F%3E%0A%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Hannah%20Ramage%20with%20the%20Lake%20Superior%20National%20Estuarine%20Research%20Reserve%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”blue-green algae”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”blue-green algae”},”type”:”media”,”field_deltas”:{“1”:{“alt”:”blue-green algae”,”title”:”blue-green algae”,”class”:”media-element file-embed-landscape”,”data-delta”:”1″,”format”:”full_width”,”alignment”:””,”field_image_caption[und][0][value]”:”%3Cp%3EBlue-green%20algae%20observed%20at%20the%20Barker’s%20Island%20beach%20area%20in%20Superior%20on%20Friday%2C%20Sept.%2010%2C%202021.%3Cbr%20%2F%3E%0A%3Cem%3EPhoto%20courtesy%20of%20Hannah%20Ramage%20with%20the%20Lake%20Superior%20National%20Estuarine%20Research%20Reserve%3C%2Fem%3E%3C%2Fp%3E%0A”,”field_image_caption[und][0][format]”:”full_html”,”field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]”:”blue-green algae”,”field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]”:”blue-green algae”}},”link_text”:false,”attributes”:{“alt”:”blue-green algae”,”title”:”blue-green algae”,”class”:”media-element file-full-width”,”data-delta”:”1″}}]]

It’s unknown whether the Barker’s Island bloom contained toxins as samples are still undergoing analysis by the Wisconsin State Lab of Hygiene. But, scientists are keeping a close eye on blooms as climate change drives temperatures higher, warms lakes and causes more extreme weather events setting the stage for harmful algal blooms. The changes could spell trouble for the world’s largest freshwater lake by surface area, which is one of the fastest warming lakes across the globe. Sterner thinks more blooms are likely — even in the typically cold, pristine waters of Lake Superior.

Brenda LaFrancois had made a mental note about the potential for a bloom on the same weekend that a fellow park ranger reported blue-green algae while kayaking in the sea caves on July 18. Lake temperatures were already warm, and the forecast had called for a stretch of hot, calm weather.

“From our historical analysis, we know that the big bloom years tended to occur in years that also had lots of precipitation and flooding and riverine nutrient inputs,” said LaFrancois, an aquatic ecologist with the National Park Service. “But, we can see these smaller blooms pop up in years with more moderate precipitation or even in drought years like we saw this year.”

Abnormally dry to severe drought conditions have been seen across the Lake Superior basin this year. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers reported the Lake Superior basin has seen about 75 percent of its average rainfall in the last year through August.

Photo courtesy of Stephanie Palmer with the National Park Service

This year, Lake Superior has been the focus of a binational effort to coordinate monitoring and science under the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement known as the Cooperative Science Monitoring Initiative. LaFrancois said that’s been a “shot in the arm” for algal bloom research on the lake.

Since 2019, Northland College in Ashland has been investigating why blooms haven’t yet been found in the Chequamegon Bay of Lake Superior. The Mary Griggs Burke Center for Freshwater Innovation at Northland has trying to determine what sources of blue-green algae are in the bay and conditions that may prompt a bloom to occur.

Matt Hudson, the center’s associate director, said they’re surprised blooms haven’t popped up in the bay. It’s fairly shallow, warm and sees a fair amount of runoff from surrounding tributaries. The type of algae found on the other side of the Bayfield Peninsula in the Apostle Islands hasn’t yet been spotted in the bay.

“It’s an interesting puzzle, and we’re hoping to really hone in on what’s going on here and why some parts of the lake it blooms and why others don’t,” said Hudson. “It’s going to be a really important question for managers and the public.”

Researchers are using DNA sequencing as part of their monitoring efforts to determine the types of algae collected in samples all along the south shore of Lake Superior, as well as their interaction with water conditions or other organisms.

Northland College researchers sampled 27 different locations around the Chequamegon Bay from the Onion River to the Bad River to see what systems or streams contribute blue-green algae cells that can cause blooms to form. Hudson said a couple sites where they collected samples from the Bad River showed some sort of blue-green algae response in their lab, but the type has yet to be identified.

Sterner with the Large Lakes Observatory fears the impacts blooms may be having on the reputation of Lake Superior as a cold, freshwater lake and could in turn affect tourism. He said researchers need to understand better whether these blooms are just the tip of the iceberg.

“We’re watching the system change in ways that we just don’t want it to change,” said Sterner. “To see these blooms become larger and more frequent, that would be a scenario for the future that I don’t think any of us want to see.”

The International Joint Commission, which oversees work to protect and restore the Great Lakes, has called on the U.S. and Canada to develop models to predict blooms, enhance monitoring and increase investments in efforts to reduce runoff in Lake Superior.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.