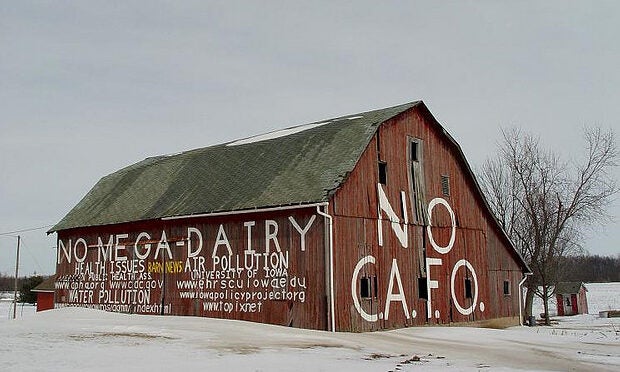

Wisconsin is home to a growing number of large animal farms known as concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs.

While agribusinesses have a tremendous impact on the state’s economic viability, they pose the potential to pollute local drinking and surface water.

Wisconsin WPDES Permitted CAFOs. Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Some residents living near the large farms — especially in areas with porous soils — have raised concerns about the quality of their drinking water.

Those in Kewaunee County — home to 14 CAFOs — have even said they’ve become ill from drinking their water.

Mick Sagrillo, whose small rural property is surrounded by large farms, has stopped drinking water from his well as a precautionary measure.

Every week Sagrillo drives to a grocery store in Green Bay, 20 miles away from his home, to fill two, five gallon jugs of water.

Sagrillo spends the extra time — and about $10 a month — on buying water because he’s worried that harmful amounts of a chemical compound called nitrate found in liquid manure have gotten into his well.

Mick Sagrillo pours drinking water from a jug, in his kitchen in Kewaunee County. Chuck Quirmbach/WPR

“I mean, there’s the deleterious effects of what could possibly happen over time. I don’t think erring on the side of being cautious is being too cautious at all,” Sagrillo said.

Sagrillo says he could spend $15,000 on a deeper well, but he’s not sure if that would alleviate his concerns. That’s because Sagrillo’s home is in a karst region of the state, where the soil is shallow and sits over fractured bedrock, making it easier for contaminants to get into the groundwater.

According to the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, the state’s agriculture business contributes more than $88.3 billion to the state’s economy — much of that from dairy or large animal farms. And as of January 2017, Wisconsin was home to nearly 300 CAFOs.

In order to protect Wisconsin’s water, the DNR requires these farms to meet performance standards. The state also regulates waste storage structures and manure application at CAFOs under the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Clean Water Act’s pollutant discharge permit program, according to the DNR.

The DNR is also looking to limit the spreading of liquid manure in 15 eastern Wisconsin counties with shallow soil.

But Jodi Parins, a plan commission member in the Town of Lincoln in Kewaunee County, says the state should follow research results compiled during a DNR committee process, and ban manure spreading on shallow soil.

“The (Walker) administration has been saying for the last three years, ‘We’re going to have to make decisions on sound science’ — now, we have the science, and they threw that out the window,” Parins said.

While the debate about manure spreading continues, a handful of CAFOs in Kewaunee County are asking the state to let them increase the number of cows at their operations.

In late November, the DNR held a hearing in Luxemberg on granting or renewing permits for five CAFOs in Brown and Kewaunee counties.

Dan Niles was one of the permit-seekers. He’s co-owner of Dairy Dreams LLC and one of the farms near Sagrillo’s house.

Niles is also a leader of Peninsula Pride Farms Inc., a coalition that promotes sustainable farming practices.

He called the DNR’s plan to limit liquid manure spreading, “an attempt to just tighten up some practices to be more productive with the groundwater.” Adding that for the most part, “it’s a good effort.”

Jeff Endres, owner of Endres Berryride Farms, LLC in Waunakee, is experimenting with new ways to spread manure that minimize risk to the state’s groundwater.

Standing inside a 220-foot-long metal shed with a roof to keep out moisture, Endres described the stages of converting solid manure into compost.

“On the left hand side is the more fresh manure, and to the farthest to the right is the more finished product,” Endres told WPR in November.

Rows of compost at Endres Berryride Farms, LLC in Waunakee. Chuck Quirmbach/WPR

Endres said when he spreads the material on his hay fields next summer, a lot of the liquid will be out of the waste, and it will be less likely to runoff and pollute local waterways.

“Compost actually absorbs moisture, so it does not leach,” he said.

Not all of the waste from Endres’ roughly 500 cows goes into compost. The manure that isn’t turned into compost is primarily injected into the soil, instead of being tilled, which is another way to reduce runoff.

Endres Berryride Farms is part of a coalition called Yahara Pride Farms, a group that strives to improve water quality in the Yahara River watershed while balancing farm profitability.

While environmentalists praise the coalition, they say there’s no silver bullet for solving runoff problems, especially as dairy farms across the state continue to grow in numbers and size.

This story is part of a yearlong reporting project at WPR called State of Change: Water, Food, and the Future of Wisconsin. Find stories on Morning Edition, All Things Considered, The Ideas Network and online.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.