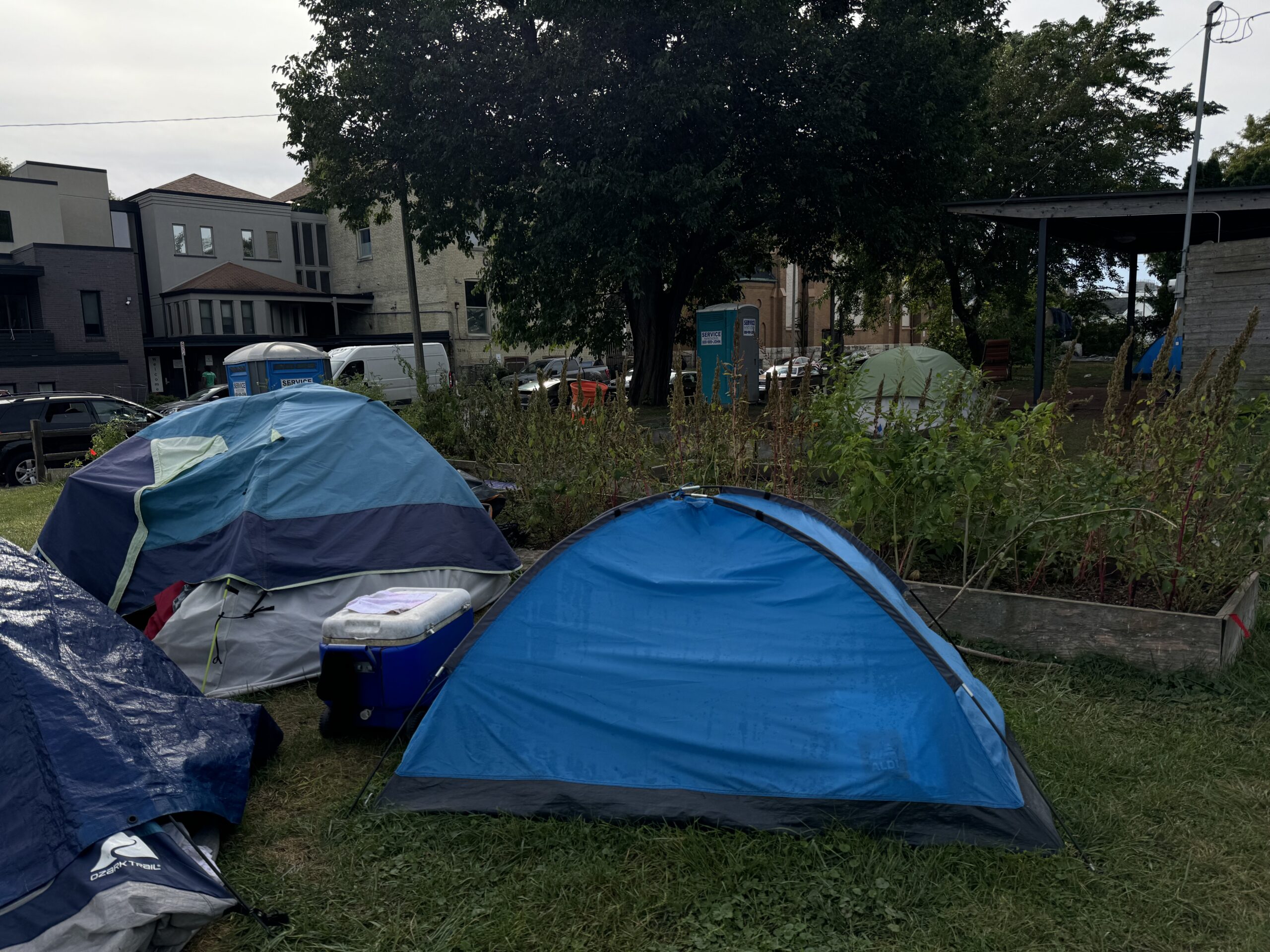

Incarcerated people are more likely to struggle with addiction or mental illness. But after being released from jail, many former inmates find themselves without health insurance.

That leaves them vulnerable to relapse or even drug overdoses, according to federal lawmakers who are renewing their push to close a gap in Medicaid coverage.

Under federal policy, incarcerated people generally cannot be covered by Medicaid unless they’re being treated in a hospital. But, once they get out, former inmates could face a wait up to a month before they’re enrolled in that program.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Bills reintroduced Thursday in both the U.S. House and Senate aim to prevent that lapse by allowing states to restart medical coverage for incarcerated people up to 30 days before they’re released.

More than 70 percent of people in U.S. jails or prisons have been diagnosed with at least one mental illness or substance abuse disorder, according to the National Judicial Task Force To Examine State Courts’ Response to Mental Illness.

That’s much higher than the rate for the general population, and former Dane County Sheriff Dave Mahoney says it’s among the reasons why uninterrupted health care coverage is so important for people being released from jail.

“Having a continuity of care program that existed while they were incarcerated keeps the cost of health care down because during an overdose, during transport in a medical emergency the costs are sky-high,” said Mahoney, who formerly led the National Association of Sheriffs and has advocated for the proposal, known as the Medicaid Re-entry Act. “I believe that it’s fiscally responsible and morally responsible to provide access to health care for these individuals returning into the community. I think that it makes our community safer.”

U.S. Senator Tammy Baldwin, D-Wisconsin, joined her Republican colleague Sen. Mike Braun of Indiana in re-introducing the Medicaid Re-Entry Act this week. It’s paired with a U.S. House Bill that also has bipartisan sponsors.

Last session, lawmakers narrowly defeated a version of the Medicaid Reentry Act, which was tucked into the Build Back Better Act.

Dr. Laura Hawks is a primary care physician who conducts public health research through the Medical College of Wisconsin. She says, during the first two weeks after they’re let out of prison, people are especially at risk of health problems and even death.

“Studies show that the time period after release is very, very high risk, not only for sort of worsening chronic disease outcomes, so, you know, blood pressure getting out of control, diabetes getting out of control, relapse to substance use, but actually mortality,” she said. “Part of that is because we have such poor communication between the health care system in prison and the health care system outside of prison. The Medicaid Re-entry Act would help sort of bridge that gap and allow those services to be continuous.”

Marianne Oleson spent more than five years behind bars and now advocates for reform through a group called Ex-Incarcerated People Organizing of Wisconsin. She says continuous coverage is crucial, especially for people living with mental illness or addiction, and notes getting treatment is often a condition of release.

“You’ve just come out of prison,” she said. “You don’t have a job. You may not have a home. You know you have to get therapy, or you could potentially go back to where you just came from.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.