Last fall, Crystal Wozniak headed to the Grant family home in Green Bay. Armed with testing swabs and informational packets, she had come to check the house for lead poisoning hazards.

Wozniak started helping families identify lead after finding out her own son was poisoned back in 2013. At his 9-month checkup, his blood-lead levels were more than three times the federal threshold.

“That’s when I found out about it and was pretty shaken up at the fact that it was actually in my little 9-month-old’s system already.” Wozniak said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Lead poisoning from water in Flint, Michigan, has drawn national attention in recent weeks: Thousands of people there were exposed to high levels of the metal after officials switched water sources in a cost-cutting move. However, lead contamination in the water is also a concern in Wisconsin. Almost 4,000 children under age 6 were found to have elevated blood lead levels in 2014, and lead from drinking water may be a cause.

A Pollutant In The Plumbing

Lead isn’t a naturally occurring contaminant in Wisconsin drinking water. It comes from plumbing like pipes, faucets and solder, which wear down over time. When that happens, it causes lead to leach into the water.

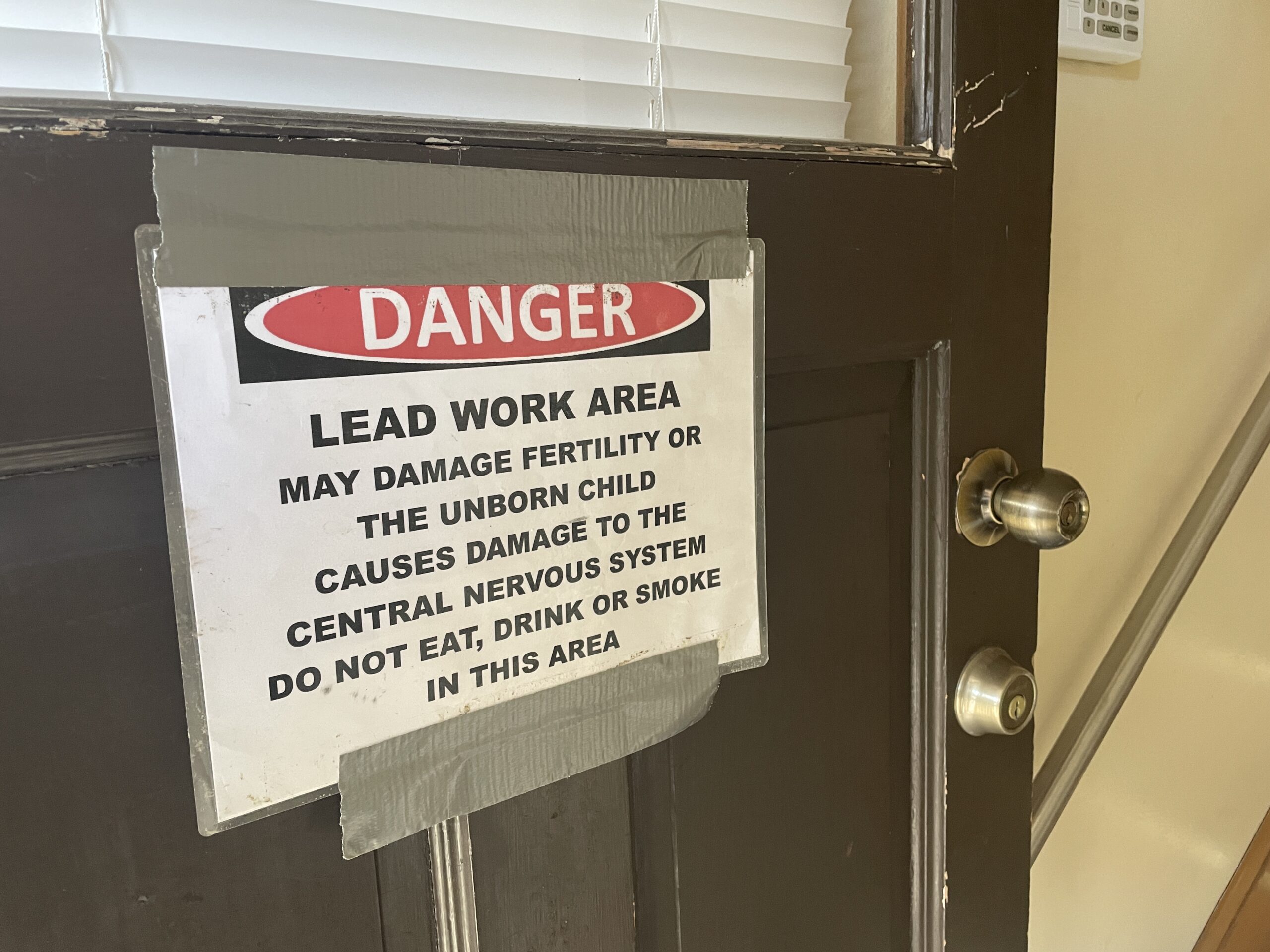

During her visit to the Grant home, Wozniak examined the pipes in the house’s basement, where the family had been thinking about setting up a playroom for their two young children. She pointed out a section of plumbing where two pipes had been joined with solder: “It appears to be turning pink already,” she said.

Lead from corroded pipes in Flint, Michigan, is partially to blame for a public health crisis in the impoverished community. Siddhartha Roy/FlintWaterStudy.org

Virginia Tech engineering professor Marc Edwards has been pushing the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to update laws governing lead in drinking water. Virginia Tech

Pink, Wozniak said, means there is lead.

“Most moms or families do want to protect their kids, and there’s just so many people that don’t know about this hidden hazard and how badly it affects young children,” she said.

Lead exposure can affect intelligence and lead to learning disabilities, developmental delays and disruptive behavior at school. Some studies have even linked childhood exposure to a greater likelihood of violent crime in adulthood.

Marc Edwards, a civil engineering professor at Virginia Tech and an expert on lead contamination in water, said this isn’t a new problem.

“We’ve known for 2,000 years that as long as water flows through lead pipe, you’re going to pick up some lead in the drinking water,” Edwards said.

“Even the Romans knew,” he added. In fact, the word plumbing derives from the Latin word plumbum, which means lead.

Lead pipes were banned in 1986, although up until January 2014, “lead-free” plumbing components like faucets could legally contain up to 8 percent lead. Regardless, people in more than 22,000 Wisconsin homes may still be consuming unsafe levels of lead in their water, according to an analysis of testing data done by the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism.

Costly Solutions

Fixing the problem would be complicated and expensive. Ideally, the part of the pipe owned by the utility that leads into a home would be replaced, along with the part owned by the homeowner. But Edwards said that’s not required, and in many cases utility companies will only replace their part of the pipe.

“They do it because they like to tell people, ‘Yeah, you might have lead in your water, but it’s not our lead,’” he said.

Edwards said this partial fix can even make the problem worse: “You’re disrupting this half-century or century-old pipe, and lead rust and actual chunks of lead are falling off into the water.”

That why starting in 2001, Madison replaced all the lead pipes in its system, even the privately owned parts. Madison Water Utility water manager Joe Grande said the program was the first of its kind, and now serves as a model for other cities across the country.

“I’m a strong advocate of getting the lead out and doing full-service replacements, and I think other communities can learn from the way that Madison has done it,” Grande said.

Beyond Madison, though, there are still at least 176,000 lead service lines in Wisconsin and probably many more.

Correction: The original version of this story spelled a woman’s name as Crystal Wozniack, and then again as Crystal Woznick. The woman’s actual name is Crystal Wozniak.

Editor’s Note: This series looking at lead in Wisconsin drinking water was produced in partnership with the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism. For more, visit wisconsinwatch.org.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.