Crystal Pauley, a former physician assistant, didn’t believe in so-called chronic Lyme disease — until she became sick.

Many health care providers reject chronic Lyme disease as a diagnosis. One 2010 survey found that just six out of 285 primary care doctors surveyed in Connecticut — an epicenter for the tick-borne infection — believed that symptoms of Lyme disease persist after treatment or in the absence of a positive Lyme test.

When Pauley worked for the La Crosse, Wisconsin-based Gundersen Health System, she remembered hearing about a friend from high school battling chronic Lyme in Australia. But she had her doubts. “I’m working in the medical field,” she said. “We’ve never learned about that.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Years later, Pauley has changed her mind. Pauley tested positive for Lyme in 2020. She suffers from unrelenting fatigue, joint pain and brain fog. She walks up stairs sideways because of the unbearable knee pain. Pauley said she has become “pseudo-Lyme literate” because of her own personal journey.

Pauley belongs to a cohort of patients with Lyme-like symptoms but negative test results or patients with positive test results who suffer from lingering symptoms long after treatment. They call it chronic Lyme disease, while the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention labels it as Post-Treatment Lyme Disease Syndrome (PTLDS). The CDC says there is no known treatment for the condition.

“Their symptoms are always real. They’re experiencing them,” said Dr. Joyce Sanchez, an infectious-disease associate professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin who treats Lyme patients with persistent symptoms.

“If someone is having physical symptoms and isn’t feeling listened to, then they’ll have mental health repercussions and then that will impact their physical well-being,” she said. “And then it’s a spiral that if you don’t address both components of health, you’re not going to make much progress on either side. And they will continue to feel sick.”

Wisconsin Watch talked with five Wisconsin patients, all women, who have been searching for validation and experimenting with personalized treatments as part of a long and sometimes grueling battle with the illness. The infection comes from tiny ticks primarily found in the northeastern United States, including in Wisconsin — which is a hotspot for Lyme, ranking No. 5 among states for Lyme cases in 2019.

One of the five tested positive for Lyme using a two-step testing recommended by the CDC. Three others tested positive using a test not recommended by the CDC. The fifth woman was diagnosed as possibly suffering from the disease by a “Lyme-literate” practitioner.

Wide-ranging symptoms

All five patients share commonalities. They’ve never noticed the signature “bull’s eye” rash around the tick bite, the hallmark of Lyme disease, which is seen in 70% to 80% of patients. But relentless waves of rheumatologic, cardiac and neurological symptoms have flattened their lives. Some of them were previously fit and healthy.

Pauley, 37, who as a student cranked through medical textbooks, began having trouble remembering a simple medication direction. She put up sticky notes around her office to jar her memory.

Alicia Cashman, 57, runs the Madison Area Lyme Support Group. She recalled unbearable pelvic pain beginning in 2010. “This causes pain of a magnitude that makes you want to die,” she said.

The pain metastasized quickly. She felt joint pain, headaches, insomnia and extreme fatigue. “It was so bad that I just wanted to be in a dark room with no smell, no sound, no light. Your body has succumbed to this,” she said.

Shelbie Bertolasi, 47, is a stay-at-home mother in Waukesha with four children ages 5 to 24. Until about seven years ago, she was healthy and stuck to a workout routine.

Bertolasi’s health steadily deteriorated starting in early 2015 when she miscarried twins. Then, she developed a high fever, with stomach and intestinal pain. She lost 30 pounds in a month due to constant diarrhea. Doctors flagged and treated excessive bacteria in her small intestine. She felt better but gradually was beset by continual pain in her joints, back, knees and hip.

Sometimes, she loses feeling in her feet. “It’s a nuisance when you’re in the middle of (driving), and you can’t feel the pedals that well,” she said.

Judy Stevens, 52, a former school counselor and psychotherapist from Wauwatosa, says shortly after the loss of her father, she was hit by joint pain, brain fog, insomnia, hair loss and night sweats. She was an athletic person, a cross-country coach at school and a triathlete.

None of these women recalled seeing a tick, except Jessica Croteau, who lives in Rice Lake. The 34-year-old noticed a tick on her neck in the summer of 2019 at home and started to have flu-like symptoms, but she tested negative for Lyme. Croteau suffered bouts of low-grade fever, a stiff neck and gastrointestinal problems. She ended up visiting the emergency room when her blood pressure spiked.

Going down ‘rabbit holes’

Often, chronic Lyme patients present multiple symptoms that make their diagnosis challenging. They bounce from one specialist to another to tackle each problem, but each diagnosis cannot explain all of the symptoms they are experiencing.

Cashman underwent an MRI because of her severe pelvic pain, and the results found two deflating ovarian cysts which can cause severe pain in the lower abdomen. But that diagnosis did not explain the unbearable pain that gravitated to her knees and to her head. She recalled that the swollen knee “got red hot to touch,” and she developed a fever. Cashman began to look for causes. “Not everything is Lyme, but everything can be (Lyme),” she said. “It’s a weird thing, but you got to go down these rabbit holes.”

Croteau saw specialists, including emergency physicians, a cardiologist, a kidney specialist and an immunologist. All the tests she took were negative for Lyme disease. She was told the problems may be related to psychological issues.

“So basically, it’s been a timeline of two years of not being taken seriously, just pushed away — either told I can’t do anything for you (or) there’s nothing really wrong with you,” Croteau said.

A medical provider suggested that she seek counseling and increase her dose of anti-anxiety medicine. But the pain in her joints and wrists were real, and her knuckles often got swollen. The brain fog made it hard for her to punch in a phone number correctly.

Bertolasi saw a pain specialist, a psychiatrist, a spinal therapist and a neurologist. They diagnosed her with SI joint dysfunction. Back surgery, therapy and exercise relieved some of her pain, but her knees continue to hurt. She was told, “You’re getting older, (so) things don’t work as well as they used to.”

Unsatisfied, in 2019, Bertolasi saw a rheumatologist who ordered several tests, including for rheumatoid arthritis and lupus, and the results were all negative. And the forgetfulness has persisted; she has left her phone in the refrigerator.

“You’re just surrounded by this dark (mental) fog, and you just don’t know how to navigate your way through,” she said.

After seeing around 30 specialists, Stevens had a bag of medications, including many prescribed psychotropic drugs. She went on those drugs, and her psychiatric symptoms got worse. However, she doesn’t blame doctors, who generally specialize in one area of the body or a family of diseases.

“When you have a whole slew of symptoms, it’s hard for the physicians to dig deeper,” she said.

Sometimes, patients with waning and waxing symptoms are labeled as malingerers who are faking symptoms to get attention. “This is very common with people with Lyme,” Stevens said.

Sanchez, the infectious disease doctor, worries that patients who do not get answers from mainstream medicine may gravitate toward unproven — and expensive — alternatives. But she sees no harm in some strategies that may offer relief, including meditation, tai chi, acupuncture or massage therapy.

No quick fix

Two of the five women interviewed by Wisconsin Watch have been diagnosed through the CDC’s two-step testing regimen: the ELISA test followed by the Western Blot, two different ways of looking for Lyme antibodies in the patient’s blood. Pauley tested positive for Lyme using the CDC’s recommended criteria, and Stevens tested positive on just one of the two tests.

Two others used a laboratory that administers the same tests but uses less-stringent criteria to determine whether a person has Lyme. Cashman and Bertolasi both tested positive through that testing. A 2014 Columbia University study found that some labs using their own criteria reported more false positive results — 57% — among people with no history of Lyme than the 25% false-positive rate using CDC criteria. Croteau used three different laboratories but tested negative each time.

With a Lyme disease diagnosis, Pauley took the standard treatment, doxycycline, for three weeks.

But when she completed the antibiotic therapy, she felt even worse. While her memory has improved, she has developed muscle pain, and her knees hurt even more. She felt tired, saying she could sleep 10 to 16 hours a day. But her doctor, following standard protocol, has told her she is done with treatment.

The same thing happened to Stevens. The doctor prescribed her 30 days of doxycycline and suggested that she seek a “Lyme-literate” doctor as she could not prescribe any longer course of antibiotics.

Stevens’ doctor followed CDC guidance, which recommends against prolonged antibiotic treatment, saying the harm outweighs the benefit. Sanchez echoed the argument, saying that doctors must weigh the risks and benefits of antibiotics, just like other prescribed medications.

“If we don’t see any plus side benefit to it, then we’re only exposing people to unnecessary risks,” she said. “Nothing comes with a free lunch. It’s important to be thoughtful about the right antibiotic at the right dose for the right amount of time.”

She also said some antibiotics could bring down inflammation as a side effect, making some patients feel better. This is also the point at which some patients begin experimenting with treatments that mainstream medicine does not recognize.

Sufferers try unconventional treatments

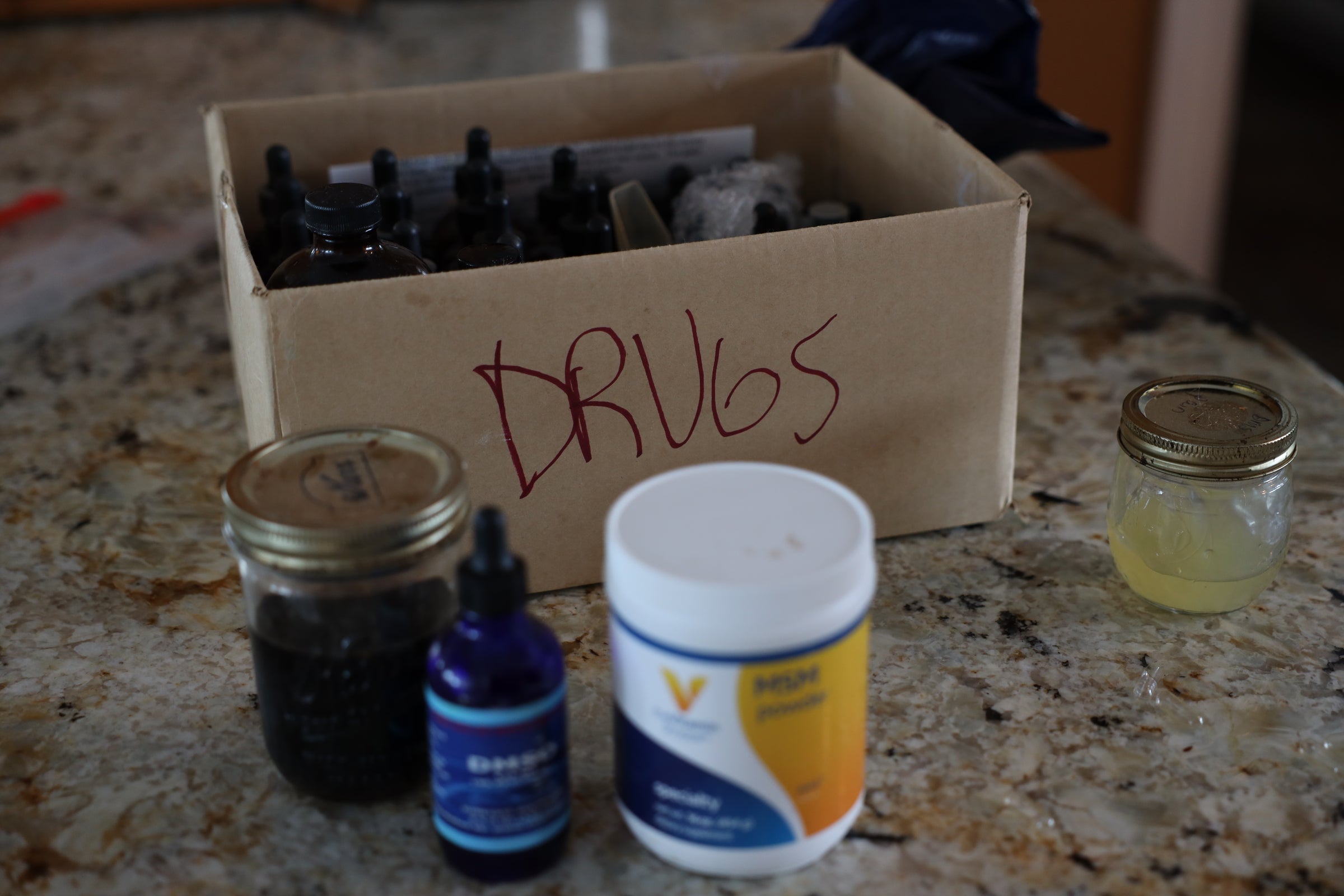

Cashman, living in Cataract, Wisconsin was also diagnosed with Bartonella, or Cat scratch disease, and went through five years of “systemic, holistic” treatments, which included a host of herbs, antibiotics, a high dose of vitamin C and supplements. She also received ozone therapy and laser therapy for pain relief. She is now nearly symptom-free, but still deals with spine stiffness.

Stevens found two Lyme-literate doctors in Wisconsin who are versed in both Western and alternative medicine. She said she was co-infected with Relapsing Fever, Babesiosis and Bartonella. She said her treatments are highly individualized, and her doctors tweak her therapies from time to time. At one point, Stevens was on more than 40 types of herbs and supplements.

“I’m living proof that I got better as a result of all those herbal treatments,” she said. “I was not on antibiotics for four or five months.”

Bertolasi turned to a Lyme-literate doctor who also treats one of her friends with similar symptoms. Besides Lyme, she was also diagnosed with Bartonella. She has completed a 14-month course of antibiotics. Now, besides taking herbal supplements, Bertolasi follows a strict diet excluding alcohol, dairy, gluten and sugar to reduce inflammation in her body.

She said she is at least 80% better than about a year ago. Her memory has somewhat returned. Still, brain fog waxes and wanes — as does pain in her joints and lower back.

Croteau tested negative with three Lyme disease tests, but she was diagnosed by a Lyme-literate doctor with Bartonella and “questionable” Lyme disease. The doctor prescribed her doxycycline, triggering a severe reaction that Lyme-infected patients sometimes experience during treatment.

When Croteau found herself pregnant, the doctor suggested she take amoxicillin and clindamycin in low doses during her pregnancy. She stopped taking them after giving birth to her second child in late October 2021 and has been symptom free for the following two months. Croteau said her symptoms have returned since January, including fatigue and brain fog, neck stiffness, headache and nausea. She cares for her newborn at home and hasn’t started any treatment due to financial constraints.

‘A rich person’s disease’

Since chronic Lyme is not a recognized disease, it’s difficult to get insurance coverage, so patients are usually stuck paying out of pocket for treatment.

Pauley, who lives in Woodstock, Illinois, is still searching for affordable treatments. Her dementia-like symptoms made it impossible to continue working as a veterinary assistant, and she quit her veterinary clinic job in 2020. Previously, she had quit her physician assistant job in La Crosse and moved back to Illinois.

“It was hard,” she said. “I went from the middle-upper class to the poverty line.”

She went to see a Lyme-literate doctor in Milwaukee in August, when she was also suspected to have Bartonella. Pauley was charged $525 per hour for the initial consultation fee, not counting testing fees and supplements. She was irritated to hear the doctor refer to it as “a rich person’s disease.”

“It’s hard to understand any doctors that charge like Beverly Hills lifestyle out in the Midwest,” she said. “We’re not celebrities, and I don’t get paid 30 million per film.”

Stevens said her average costs out of pocket range from $25,000 to $50,000 a year. “It was a huge strain on us,” she said. “This is why a lot of people can’t get better, because they can’t afford it.”

Cashman knows the financial burdens chronic Lyme patients bear, too.

She estimates she has spent $150,000 out of pocket for treatments that she and her husband — who also is a chronic Lyme patient — have taken over the years. Cashman has found ways to reduce the costs by, for example, buying pounds of ground herbs and making her own capsules at home.

Although all five women interviewed by Wisconsin Watch have tried unconventional treatments, they say they are skeptical about anyone who claims their chronic illness can be cured quickly.

“(If it) is just a quick fix to make money, and I’m just very leery of it,” Bertolasi said.

And they are using their experiences to help others. Pauley has become an advocate for lower health care costs. Bertolasi is writing a Lyme-friendly cookbook to chronicle recipes that have worked for her.

Although Stevens said being a chronic Lyme patient is “like a full-time job,” she wants people to know there is hope.

“You can be in terrible shape, but you can get better,” Stevens said. “It’s really easy to go down the road of ‘poor me,’ but it is possible to get better. There is hope. You can reach remission.”

The nonprofit Wisconsin Watch (www.WisconsinWatch.org) collaborates with WPR, PBS Wisconsin, other news media and the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by Wisconsin Watch do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.