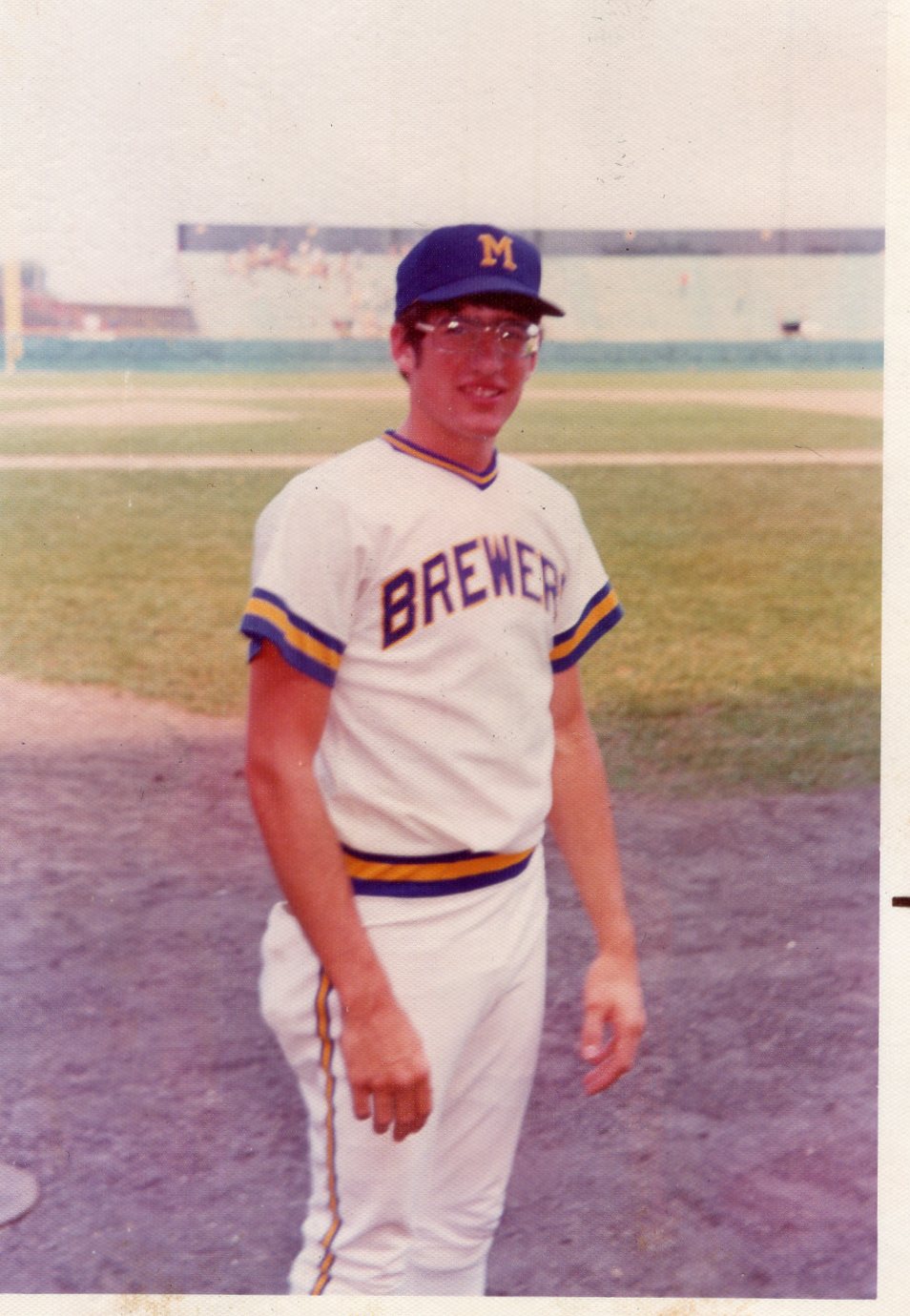

After the Milwaukee Braves relocated to Atlanta in the mid-1960s, an eager 15-year-old Patrick McBride saw an ad in the Milwaukee Sentinel offering a chance to be a batboy for the new Brewers team.

McBride was interested. But he doubted his ability to write an essay required for the job. He and his twin brother grew up in a dysfunctional Wauwatosa home. He had internalized teachers calling him “the dumb twin.”

“I would like to be a batboy because I would be doing a small part toward bringing baseball back to Milwaukee,” McBride recalled writing. “I would hope the spirit I would show would be contagious.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Third baseman Eddie Mathews, who played more than a decade for the Milwaukee Braves, picked McBride’s essay among hundreds of entries. The next thing McBride knew, he was working his first day in the visiting clubhouse for an exhibition game with the Chicago Cubs. In the dugout, he heard the click of spikes walking toward him. It was Cubs legend Ernie Banks, whom McBride recalled saying, “Hey son, it’s a great day. Let’s play two.”

“I’m still getting goosebumps. I thought I was going to faint,” McBride recalled. “And then he said to me, ‘Hey son, do you want to have a catch?’”

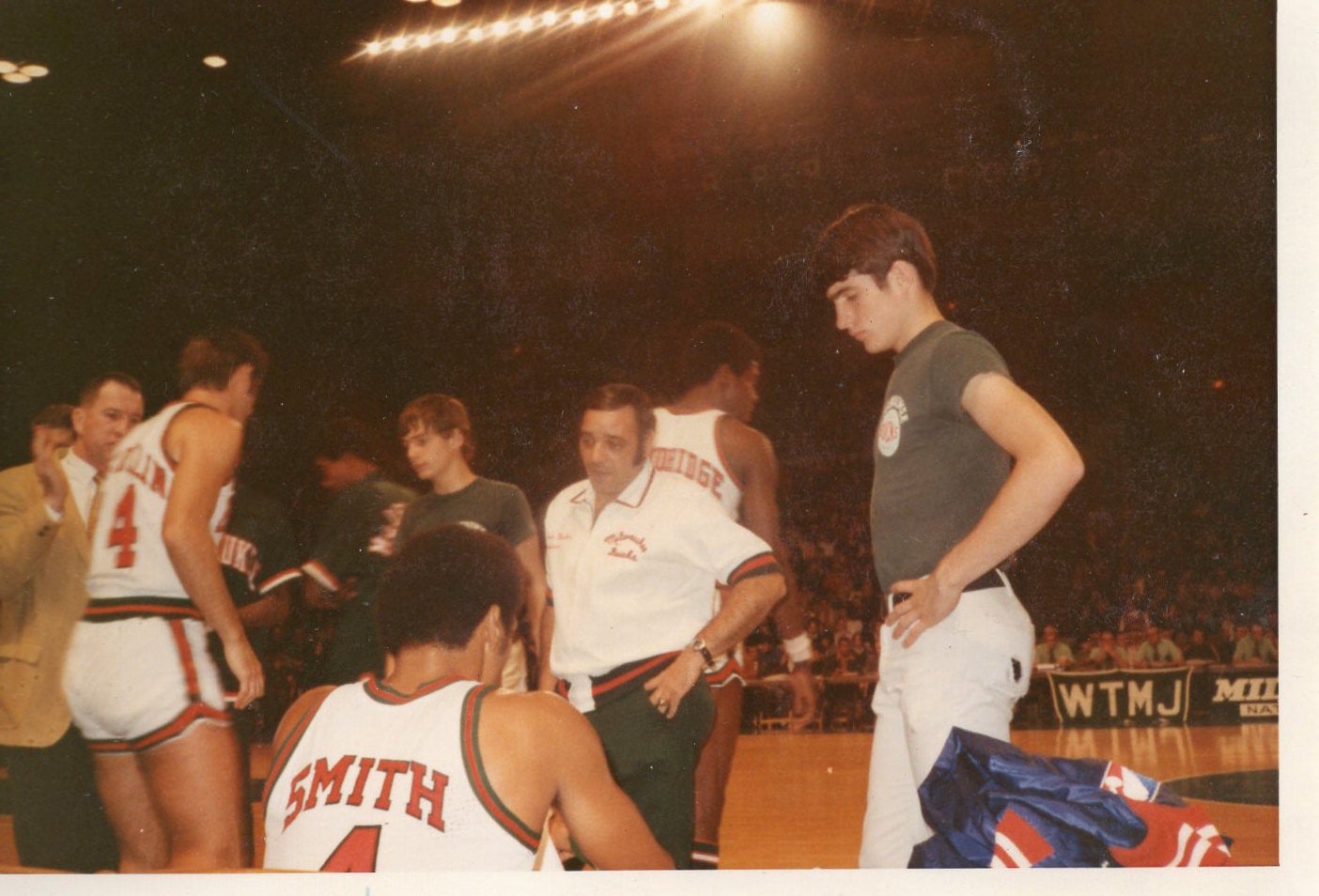

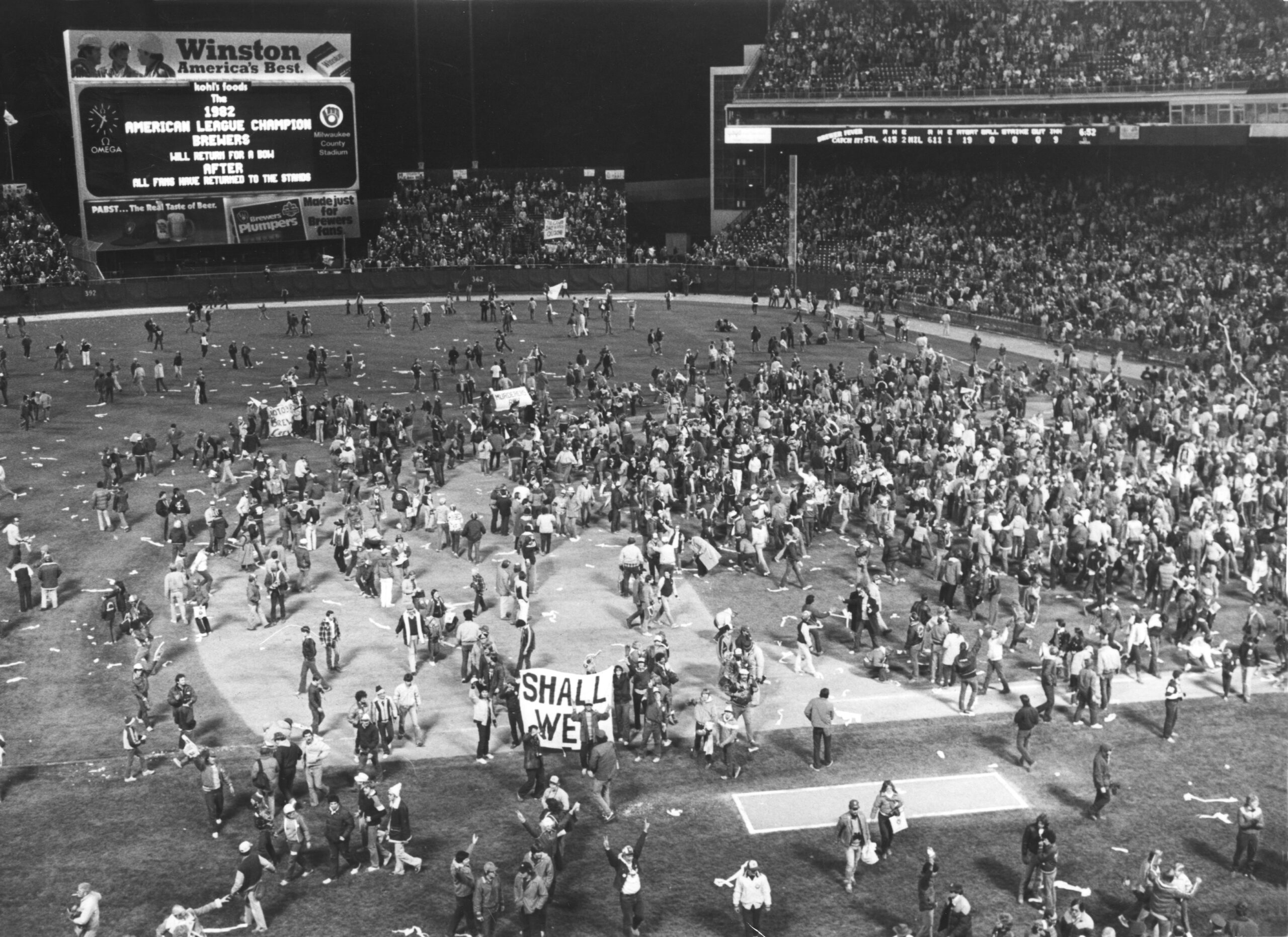

That day marked the first of many encounters the Wauwatosa teenager would have with sports legends. From 1969 to 1976, McBride worked the locker rooms and sidelines for the Brewers, the Milwaukee Bucks and some games for the Green Bay Packers. He crossed paths with Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Bart Starr and Hank Aaron — whom he called “a first-class human being.”

McBride recently discussed his years in sports on Wisconsin Public Radio’s “The Larry Meiller Show.” In 2021, he also published a book about his experiences called “The Luckiest Boy in the World.”

As a teenager, McBride’s self-doubt extended beyond his writing abilities. During his jobs with the Bucks and Brewers, he never walked anywhere. He always sprinted.

“I didn’t think I was worthy of this,” he said. “So, every game I was at, I was completely drenched in sweat.”

During his first few years with the Brewers, McBride was still a high school student. He had his counselor change his schedule so he could make his shifts unpacking bags, hanging uniforms, polishing shoes, washing laundry, lining up the bats and running other errands for players.

“I was there until (12:30 or 1 a.m.), and then I’d ride my bicycle home about 5 miles,” he said. “Then, I’d have to do my homework. I got paid $5 a game the first year and $10 the next. But you know what? I didn’t mind at all.”

READ MORE: Hank Aaron’s chase for ‘home run king’ title haunted him, author says

McBride thought he would care most about who hit the most home runs or won the most games. But he quickly appreciated how stars treated people like him behind the scenes, ranging from remembering their names to taking them out for pizza after games.

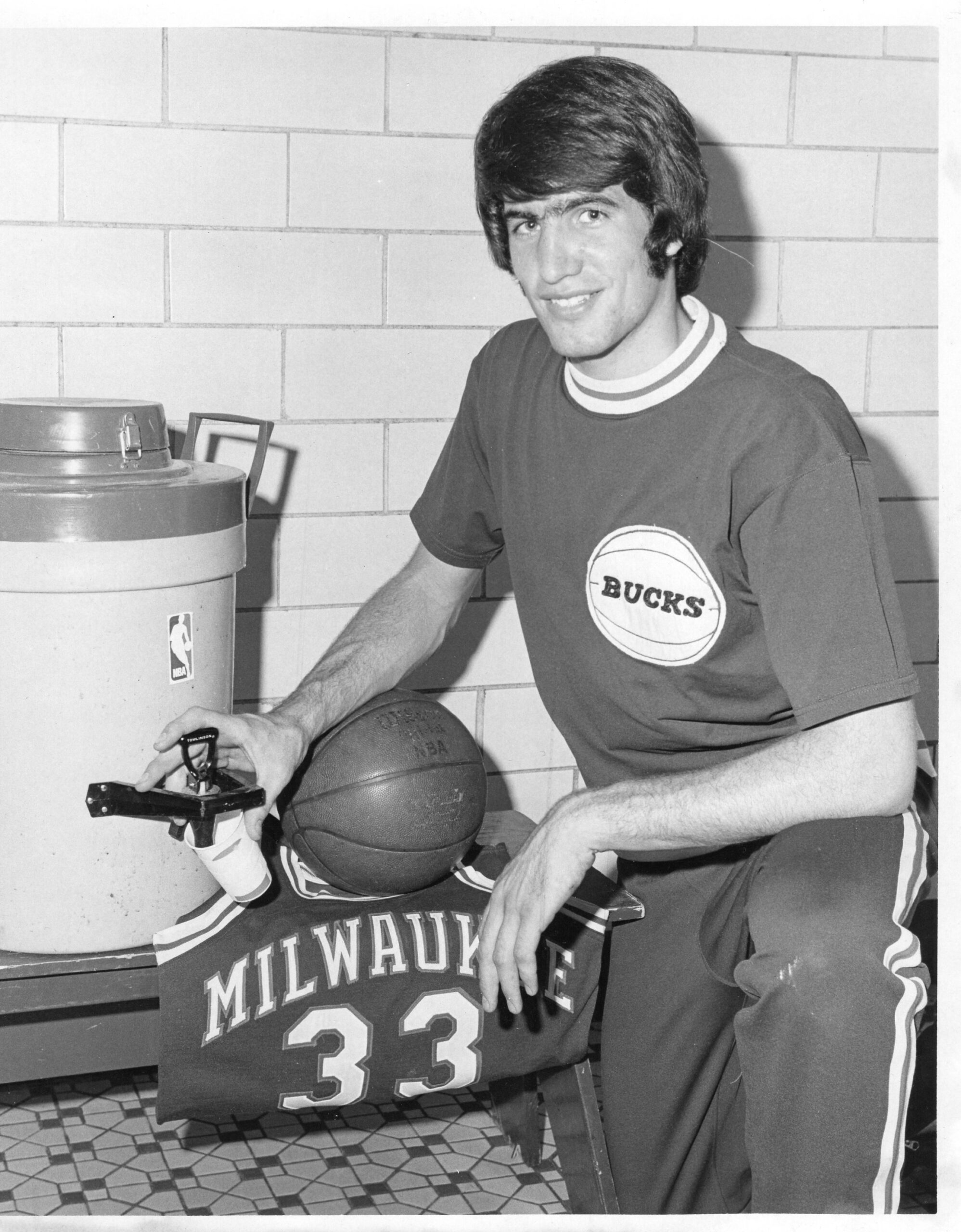

One day in 1969, McBride heard on the radio that a coin flip had awarded the Bucks the top pick in the NBA draft. He called up the team and asked for a job as a ball boy. His experience with the Brewers helped him stand out among the job interviews.

Aside from working for teams while growing up, McBride delivered newspapers, worked at a car dealership, scooped ice cream at Baskin-Robbins and mowed lawns.

“In our family, there were seven kids and all seven of us, starting at age 12, we had to pay for everything. We never got a dime from our parents after age 12,” he said. “I did whatever I could.”

READ MORE: ‘We’re just excited to be here’: Brewers fans celebrate Opening Day in Milwaukee

McBride’s responsibilities grew around age 18. The high school senior started managing a $150,000 budget as the official equipment manager for the Bucks — something he says no one younger than 21 has done in any major professional American sport to this day.

McBride hopes to inspire young people to dare to dream — just like he did. One essay contest changed his life. He lived many Wisconsinites’ dreams of working with the Brewers, Bucks and Packers.

“What kid gets to do that?” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.