Wisconsin’s two largest cities would be key pieces of an expanded high-speed passenger rail network across the Midwest, according to a new federal study.

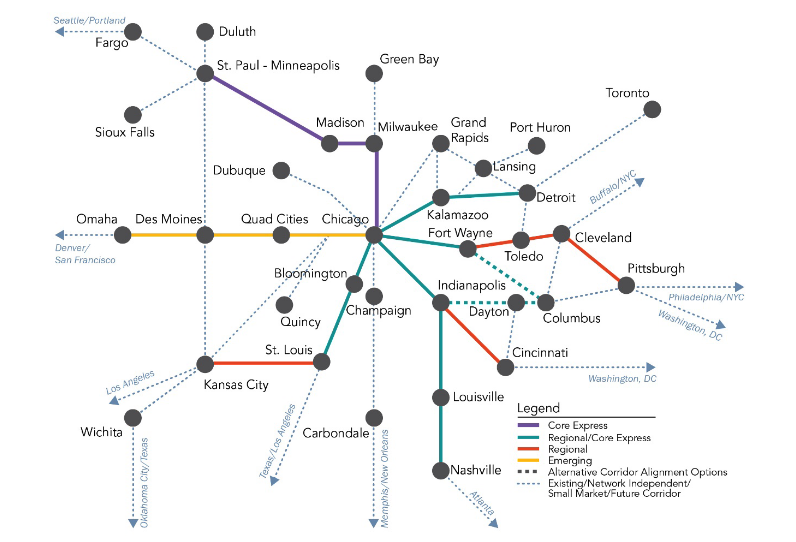

The Midwest Regional Rail Planning Study mapped out the most promising routes for development over the next 40 years. Madison and Milwaukee stood out to planners as critical links for the success of a line connecting Chicago to the Twin Cities.

Madison transportation director Tom Lynch said he’d like to see such a line in the Madison area.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I think there’s promise, and we’d like to make sure that we can take advantage of bringing conventional passenger rail service to Madison as soon as it’s possible,” Lynch said.

The Federal Railroad Administration led the study, in collaboration with stakeholders across 12 Midwestern states. According to the report, the Midwest boasts the nation’s most complex regional network of passenger, commuter and freight rail, with Chicago as is its main hub.

Using population, market demand and ridership data, the study identified four pillar corridors for development: Chicago to Minneapolis-St. Paul; Chicago to St. Louis; Chicago to Indianapolis; and Chicago to Detroit. Of these four corridors, Chicago to Minneapolis-St. Paul; is the only route that doesn’t exist as a commuter line. Currently, the only way to get from Chicago to the Twin Cities by train is on the Amtrak Empire Builder — a cross-country route that only runs once a day.

The FRA study used statistical modeling to examine five possible configurations for the new route. The report concluded the only viable options included stops in Milwaukee and Madison.

Seeing Madison as part of one of the options is important, said Philip Gritzmacher, a transportation planner for the city of Madison.

“They’re highlighting that backbone network and bringing Madison into it, saying upfront that we are a core part of the missing core route,” Gritzmacher said.

While the routes outlined in the study are only speculative at this time, they offer a sketch of what the future of intercity passenger rail service in the Midwest could look like, including the potential for high-speed rail.

According to the FRA, the next steps will be initiated and led by the states and other stakeholders involved. This would involve prioritizing the corridors for development, conducting more detailed follow-up studies, and developing the regional governance structure that would be necessary for implementation.

But local officials say there is a long way to go before most of this could happen. While high-speed rail may be the long-term vision, it is costly and time-consuming to develop, which makes it challenging to meet more immediate needs.

Earlier this year Amtrak released its own 15-year plan, focused on improving existing routes and bringing conventional service to new areas. Under the plan, the Chicago to Milwaukee Hiawatha line, Amtrak’s most popular Midwestern route, would increase from seven to 10 trips daily. Amtrak would then extend the line to Minneapolis-St. Paul and add branch lines to Madison and Green Bay.

While Amtrak is more focused on the near-term, they support and see their plan fitting into the broader vision for a high-speed rail network outlined in the FRA plan.

“Amtrak supports the development of high-speed rail (HSR) in appropriate corridors,” the report states. “Given the many years HSR corridors typically require for planning, permitting and construction, Amtrak is proposing to implement conventional service in the near-term that would create or expand initial markets for intercity passenger rail service and then feed complementary HSR services once built.”

Both Lynch and Gritzmacher see the Amtrak plan as a more realistic option for the near future. This would be Madison’s very first passenger rail train, so the city still needs basic infrastructure like a train station.

“Extending an already successful line, from Milwaukee to Madison, seems to be of interest to Amtrak, and it seems to be of interest to policymakers and the mayor here in Madison,” said Lynch.

Nonetheless, they’re on board with the FRA’s longer-term vision and excited about the possibility of heading in that direction with Amtrak’s plan.

“I would look at it as a step towards the vision outlined in the Midwest plan,” said Gritzmacher. “But we do need to maintain focus on the future as well. So it’s good that they’re both coming out at the same time so that as we dive deeper into plans for Amtrak passenger rail, we aren’t doing things that make it impossible to fulfill that national vision that was outlined in the Midwest Rail Plan.”

Both plans would depend heavily on significant and long-term federal investment and the infrastructure bill currently under consideration in Washington would be a major boost. The bill includes $66 billion for passenger and freight rail, most of which would be earmarked for Amtrak to maintain and update existing routes. The bill also includes $12 billion in grant funding for intercity rail service, including high-speed rail projects.

“We would really like to pursue getting passenger rail to Madison and we believe that with the two budget packages that are being discussed, now is as good a time as probably ever in the last 20 years,” said Lynch.

Still, while local officials are expressing optimism, this is not the first time Milwaukee and Madison have been part of a plan for passenger rail service. A decade ago, wheels were turning to create a line connecting the cities using federal funding from the Obama administration. But amid a contentious debate, newly elected Republican Gov. Scott Walker was able to derail the project, arguing it was a waste of public money.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.