After spending a decade in prison, Jarrett Adams never wanted to come back to Wisconsin — the state that wrongfully convicted him as a teenager and tried to incarcerate him for a 28-year term.

He would only return if he could do so as an attorney, a force that can operate from within the criminal justice system he saw for himself and desperately wanted to change.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

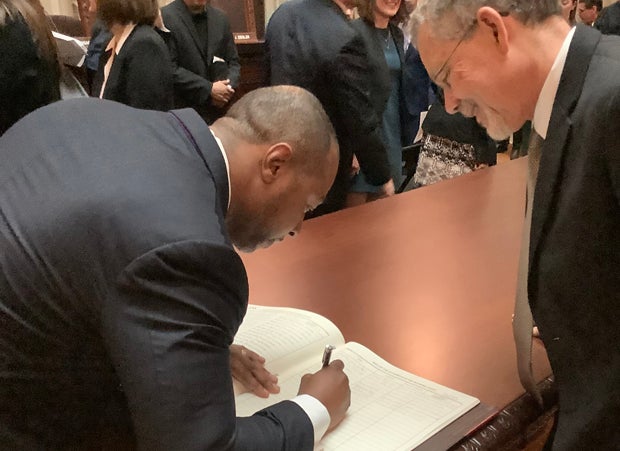

On Jan. 22, 2020, Adams was officially admitted to the Wisconsin State Bar during a ceremony at the state Capitol. Keith Findley, a co-founder of the Wisconsin Innocence Project and part of the team who helped free Adams, was there for the occasion.

Now with an eye on reform, Adams is sharing his story in a book, “Redeeming Justice: From Defendant to Defender, My Fight for Equity on Both Sides of a Broken System.”

“If the courts could see me as I am now when I was a 17-year-old, I never would have been sentenced to 28 years in prison,” Adams said recently on WPR’s “Central Time.” “I enjoyed the moment (at the Capitol), and it inspired me to keep going to create other Jarrett Adamses.”

One systemic issue Adams pointed to was about public defenders, whom he believes are often saddled with too many cases. But Adams didn’t get a public defender. Sometimes if there are conflicts of interest, for example, private attorneys take on public defender cases.

For his case specifically, he and one of the other co-defendants had to be assigned attorneys — while the third defendant could afford their own lawyer. That lawyer was “filing motion after motion after motion,” Adams said, something his assigned attorney never joined in on.

“You’re on an island, and you are facing the might of the entire system,” he said. “They’re not playing when they say, ‘State vs. whoever it is.‘”

Attorneys who represent defendants who can’t afford their own lawyers don’t make as much money on those cases — but the gap was narrowed in recent years.

RELATED: Justice delayed for those who can least afford it?

Wisconsin used to pay private attorneys who took public defender cases $40 per hour, which was the lowest rate in the country. But after seeing some bipartisan support, the state rose the pay to $70 per hour starting Jan. 1, 2020, said Adam Plotkin, legislative liaison for the state Public Defenders Office.

The pressure defendants feel when they have overworked or disinterested lawyers can manifest itself in taking plea deals when they shouldn’t, Adams said.

Adams said some defendants just make the decision that can get them out of the immediate pain they’re feeling. He knows some who pleaded guilty to their charges to get out of custody only to end up going to prison anyway for parole violations.

Adams served time at a maximum-security prison in Boscobel, which he said was built using fear as a motivator to imprison the “worst of the worst.” But in reality, he said officials had to fill the facility with inmates who were far from the likes of Jeffrey Dahmer.

He said “Draconian” sentences are leading to overcrowded prisons, and those heavy sentences remove incentives for the incarcerated population to truly better themselves.

“There’s no correcting at all going on. You’re being warehoused in this prison. You’re pretty much just getting up, going to sleep. Getting up, going to sleep,” he said. “There has to be an investment in the people that are there. Inmates are people as well.”

“Most people who are incarcerated will go home at some point,” he continued, “and we are doing a horrible job of preparing people to reintegrate back into society.”

He said the system needs more therapists, social workers and psychologists.

“We need to allow the world of therapy to mend this system,” he said.

RELATED: Wrongfully-convicted man returns to Wisconsin as an attorney

Adams said he even saw correctional officers who themselves were feeling the effects of the criminal justice system, which he argued is a sign that the system isn’t getting the results it should.

One caller into the segment said she corrected people who called it a “justice system,” preferring to use the term “judicial system.” She wasn’t sure that the judicial system featured enough justice.

In response, Adams pointed to the deep racial disparities that exist in Wisconsin prisons. He referenced a data point from an October report by The Sentencing Project that found one of every 36 Black adults in Wisconsin is in prison — a measure that is worst in the country.

“I mean that number should make everyone drop what they’re doing and turn their attention to fixing this system,” Adams said.

Nationally, that figure is one in 81 Black adults, according to the report. Black people in the U.S. are imprisoned at nearly five times the rate of their white counterparts.

“We have to overhaul the system,” he said. “And that overhaul has to be more than just changing the faucet. We need to rip up the floor and change the pipes.”

When asked if he thinks that level of systemic change will happen anytime soon, Adams said it will take a lot of time and resources from everyone involved — including from the judge’s bench and the prosecutor’s office.

This all started for Adams because he told his mom he was going to stay at a friend’s house, when instead they snuck out to a party. Throughout his time in prison, he couldn’t forget the “creases of pain and anguish on my mother’s face.”

“When I came home, I knew I had a penchant for the law, and it became a passion,” he said. “I was driven to remove the wrinkles and creases of anguish off of other mother’s faces as well.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.