Every May, high school students all around the country work through practice tests, review dates and formulas and sharpen their No. 2 pencils in preparation for several weeks of Advanced Placement exams.

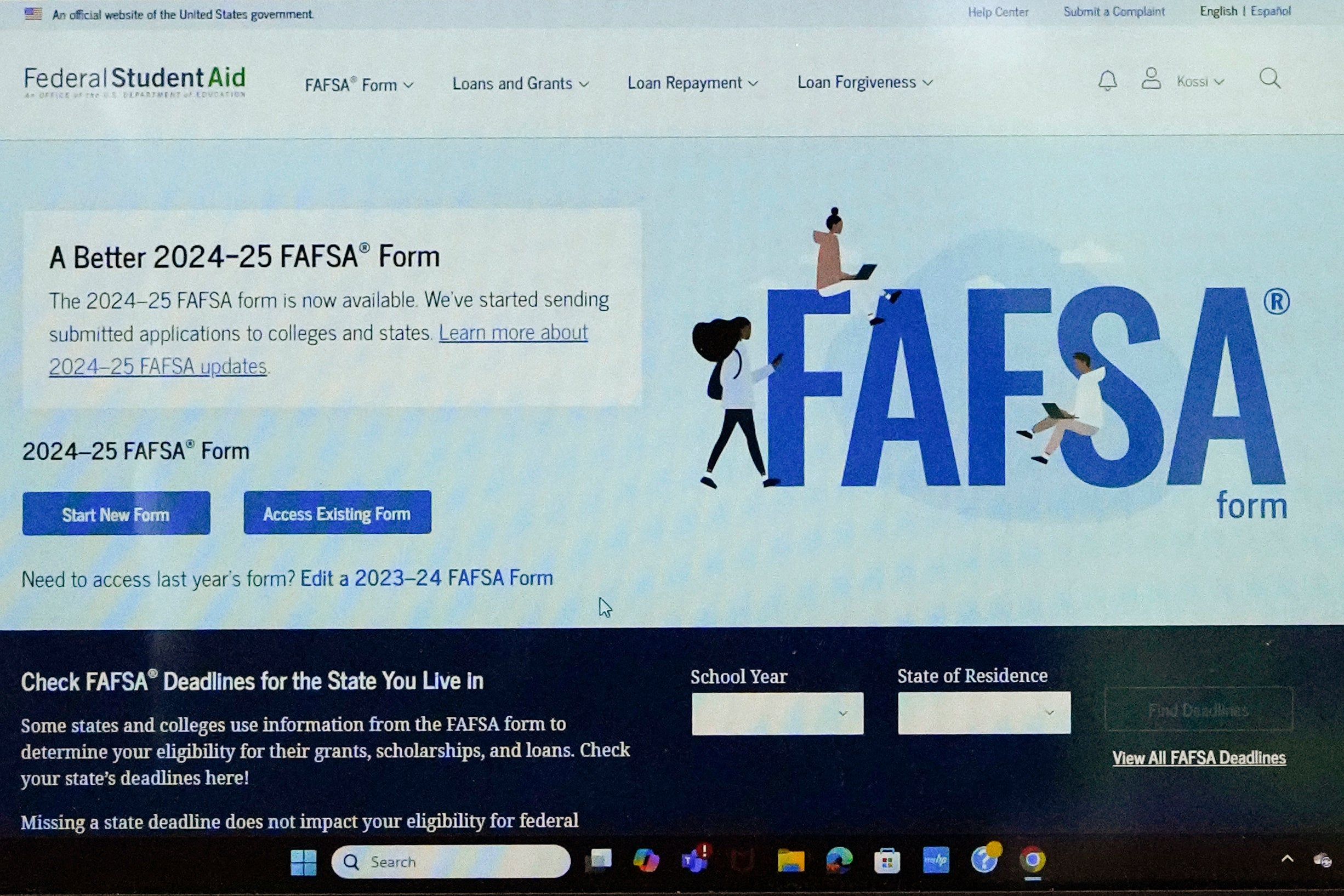

If they do well, many will be able to skip some college prerequisite courses and even go into the year with credits — an alluring money-saver as the cost of college continues to climb.

For the past two years, though, the pressure of AP exams has been kicked up a notch, thanks to the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“This has always been a stressful time for students — the first two weeks of May are this peak season,” said Amanda DoAmaral, the Milwaukee-based co-founder of the community learning program Fiveable. “These last two years have been totally unprecedented.”

Like the SAT and ACT exams for students applying to colleges, AP exams are consistent no matter where they’re being taken, which means they tend to favor students in schools with more resources and smaller class sizes. The tests also favor students who can hire a tutor or take prep classes, and who don’t have to work or take care of siblings and can therefore spend more time studying.

“They’ve always just shown what resources can do, not what students are capable of,” said DoAmaral. “Realistically, it’s hard, because in a world where college is this expensive and this difficult to get into, this is a tool that students have to try to make college more affordable, to get credits earlier, but the exams and the way that we do this is just not equitable.”

Those built-in inequities were magnified over the past year, as the pandemic hit some families harder than others, and virtual learning favored students who had reliable broadband access and a quiet place to work at home.

Last school year, when many states including Wisconsin shut down their schools in March, the College Board, which runs the AP program and tests, altered their exams — although not without serious issues. Students took much shorter tests online, and were tested on fewer topics, under the assumption that not all schools were able to pivot to distance learning in time to get through the entire year’s curriculum by early May.

For 2021, the College Board again offered online options, with schools making the call on how students would take their exams. This year, the College Board is again testing students on an entire year’s worth of material, even though many teachers struggled to get through every unit because of the disruptions of hybrid or virtual learning.

“Normally, we would have spent a lot more time going through practice tests,” said Elizabeth Anderson, who teaches AP micro- and macroeconomics at Stevens Point Area High School. “I was still teaching new content the week before the test and cramming it in to try to teach all the units.”

Stevens Point schools started the year in hybrid learning and switched to all-virtual classes between Thanksgiving and winter break. Even when schools went back to in-person learning, Wednesdays remained a virtual day. Anderson said the constant switching, as well as the challenge of getting students to focus while learning from home, led to an end-of-the-year crunch before the exams.

Her students said it was hard to stay motivated — their COVID-19 year brought a lot of stress, trauma and isolation that made it hard to focus on school. Some opted not to take AP exams, even though they’d taken the class, because they didn’t feel they had enough of a handle on the material. That’s often true in normal years, though — some AP classes only last a semester, so students take the test months after they finish the class.

“That’s always a challenge for us with first semester kids, to get them back to do review because they’re off in other classes,” Anderson said.

Even in schools that offered a totally in-person learning option, students’ access wasn’t as consistent as in a typical year.

Anna Staples, a junior at the private University School of Milwaukee, spent her first semester learning virtually because both she and her mom have health concerns that put them at high risk for severe COVID-19. Hurdles to effective virtual learning showed up immediately.

“The first day we had online classes our Wi-Fi just did not work,” she said. “My sister and I were logging into Zoom classes through my phone’s data.”

Even after Staples sorted out her internet issues, other problems cropped up periodically.

“I’ve had classes where a teacher taught the whole thing and they were on mute,” she said. “There’s not much you can do about it, just getting through and then talking to the teacher after.”

Staples took two AP classes this year, Spanish Language and Culture and U.S. History. Her teacher had prepared for a pre-planned family absence toward the end of the year, which Staples said helped them get through all the units in time to spend the last few weeks before the test reviewing and taking practice exams. In her history class, though, she said they barely finished learning the year’s content in the week before the exam. She took practice exams on her own time and scored them as best as she was able.

Still, she said, she walked out of the exams feeling confident that she’d done well — and she’s planning on taking more AP classes moving forward, including AP Microeconomics over the summer and AP Spanish Literature next school year.

DoAmaral, the Fiveable co-founder, said that even if school is closer to “normal” next year, student success is going to require a lot more than what schools were doing pre-pandemic.

“What we have to remember is that you can’t just flip a switch and pretend this didn’t happen — it’s not going to get better, even if we’re in person, it’s just going to compound all this trauma,” she said. “You have to create and be really intentional about resources to help the students and the teachers.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.