Your phone keeps ringing, buzzing. The calls and texts are coming from unknown numbers. Most of the time, you ignore them. But when you answer, there’s a complete stranger on the other end, peppering you with questions.

Welcome to Wisconsin, a swing state where every vote really does seem to count and where campaigns, consultants and media outlets hire pollsters to find out what people are thinking in the weeks and months before Election Day.

Not everyone wants to answer those calls, but Angie Jaramillo does.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“I want to show that not everyone where I live is thinking one way,” Jaramillo said. “I actually think a different way.”

Jaramillo, a self-described independent voter from Brookfield, said polls remind her of when she was a kid in school taking a vote on something in class.

“And your teacher told you to put your head down and raise your hand, but then you would kind of peek your head up and see what everybody else is doing,” Jaramillo said. “To me, that’s kind of like what a poll is. And I’m curious, I’m really curious what other people are thinking. And I want to share what I’m thinking, too.”

The problem, Jaramillo said, is that she doesn’t know which polls to trust.

“I do want to participate in polls. But I don’t feel like I can tell what’s a real poll anymore,” she said.

Jaramillo contacted Wisconsin Public Radio’s WHYsconsin with the following questions: How do you know if you’re participating in a legit poll? Are they via texts or phone calls?

WHYsconsin contacted several prominent pollsters to find out.

Who is contacting me?

The answer to this question is not as simple as reading your caller ID. That’s because respected pollsters identify themselves in different ways.

J. Ann Selzer runs the polling firm Selzer & Co., whose clients include The Des Moines Register. The data-crunching website FiveThirtyEight, which grades pollsters based on their accuracy over time, gave Selzer’s company an A+.

But when voters get a call from Selzer’s firm, they don’t see “Selzer & Co.” on their caller IDs.

“What you see when your phone rings is ‘number unavailable,’” Selzer said.

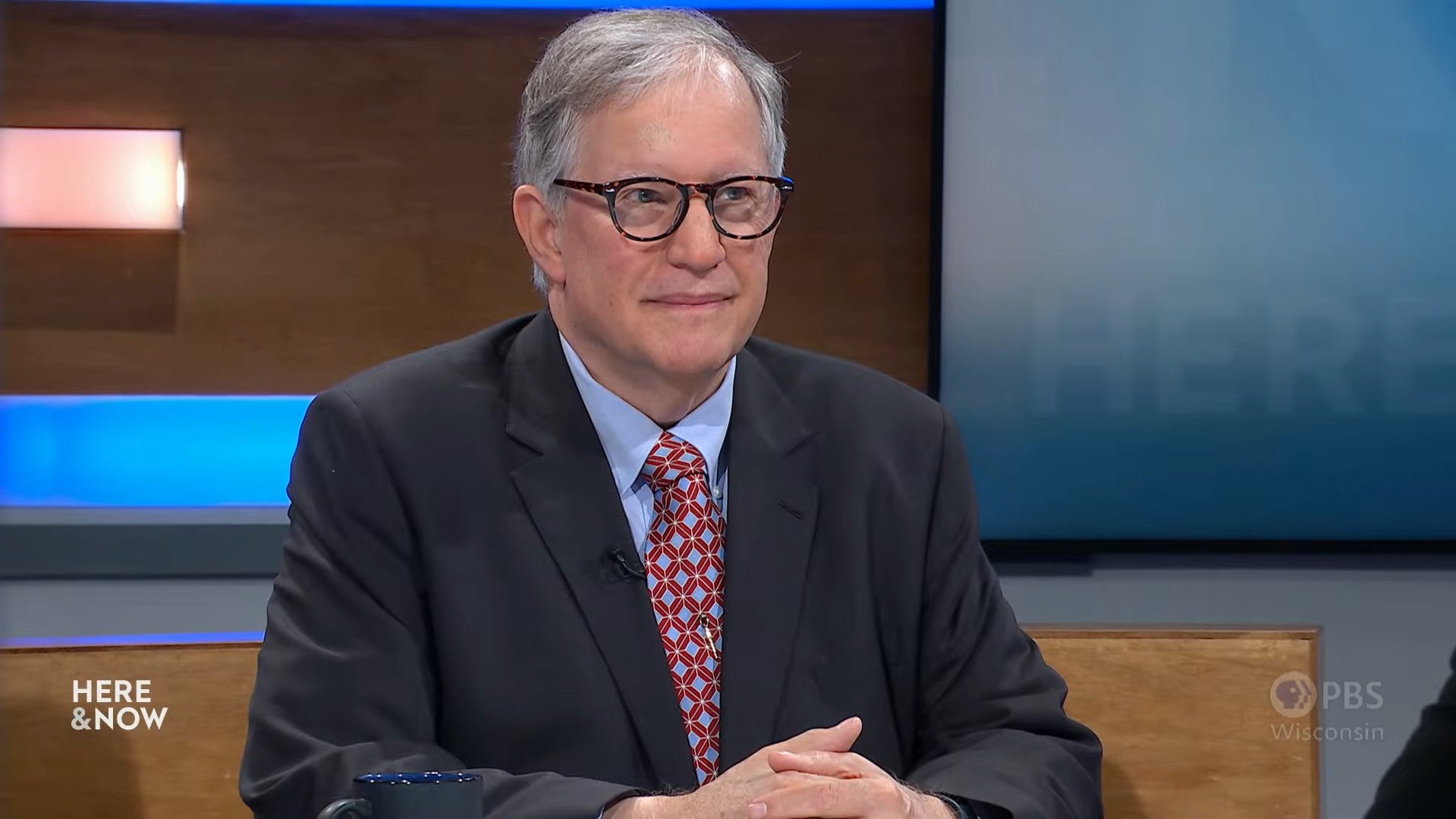

Charles Franklin runs the Marquette University Law School Poll, Wisconsin’s most prominent survey of voters. Marquette uses a slightly different approach.

“It would just show a number for us,” Franklin said. “We do not have caller ID show ‘The Marquette Poll.’”

Still, other pollsters do show up on caller ID, but their names only tell part of the story.

Dave Tollaksen is a vice president with The Mellman Group, a polling firm that works for Democrats. Like other pollsters, The Mellman Group hires outside companies — known as call centers — to contact voters. And the names of those call centers show up on caller ID for a poll conducted by Mellman.

“I’m going to make one up called the ‘American Research Firm,’ Tollaksen said. “And so it would say ‘American Research Firm’ on the phone.”

Tollaksen said all three approaches have the same goal in mind.

“We are all experimenting to try to find the right mix,” Tollaksen said. “To reach people and encourage them to engage in these polls.”

When voters pick up, Selzer said disclosure is key. The people working for her firm identify themselves immediately.

“Once they’re on the line, they will say, ‘Hello, I’m so-and-so calling from Selzer & Co., and we have some questions that we want to ask you to get your opinion,’” Selzer said. “And you either say ‘yes’ or ‘no.’ We hope you say ‘yes.’ And then we’re off to the races.”

Franklin said Marquette takes the same approach. Tollaksen said the people conducting polls for The Mellman Group will identify the name of their call center instead.

Longtime Republican pollster Gene Ulm with Public Opinion Strategies said Wisconsin also has a disclosure law for pollsters.

“Your listener can actually ask the interviewer who is sponsoring the survey,” Ulm said. “And by law, they have to tell them.”

But Franklin said the catch is that many of the pollsters who don’t identify who they’re working for up front are keeping that information private for a reason. He said it may be that they’re working for a campaign, and they’re concerned that will shape the way people respond.

“You as the respondent have every right to ask, ‘Who are you? Who are you working for?’ And they are absolutely supposed to tell you,” Franklin said. “But they’re at that point not obliged to continue the interview.”

And once those pollsters identify who they’re working for, Franklin said, they may just hang up.

Are polls using texts now?

Some pollsters are changing the way they contact potential voters, partly because it’s getting harder and harder to get people to answer phone calls. But pollsters are still divided over using text messages.

Both Tollaksen and Ulm — who often poll for political campaigns — use text messages for polling.

“The important thing for us is to reach people in a way that they are willing to engage with us,” Tollaksen said.

Ulm said he’s been polling in Wisconsin since the late 1980s. Back then, he said it would take seven calls to get one person to respond to a poll. Now, he said it takes his firm more than 100 calls to get one response. He said pollsters have had to adapt.

“Scientific survey research wants to give every eligible respondent an equal chance to participate,” Ulm said. “We’re doing more and more fusion methodologies where there’s a combination of landline, cell phones and text to web.”

Selzer and Franklin don’t use texts, and Selzer said she remains skeptical of their accuracy. She said she was at a dinner party once with a father and daughter who both received the same poll via text. The daughter, who was politically active, answered both surveys herself.

“This is what legitimate pollsters worry about with text polls,” Seltzer said. “We’d rather have control over who’s answering the question.”

Is this poll legitimate?

When it comes to Jaramillo ‘s primary question — “How do you know if you’re participating in a legit poll?” — the answer can be both straightforward and subjective.

The straightforward answer is that a legitimate poll won’t try to sell voters anything or ask for information like their credit card or Social Security numbers.

“Scammers don’t want to stay on the call with you for five to 15 minutes of questions before they try to rip you off in some way,” Franklin said. “And so unless you hear questions early that seem like they’re trying to sell you something or talk to you about your warranties or your credit card bills, I think you can be somewhat reassured by that.”

All the pollsters contacted for this story said legitimate polls follow a similar pattern in their questioning.

“There are typically some standard questions that pollsters will ask at the beginning,” Selzer said. “They might ask your age. They might ask your specs just to be sure that they’re tracking with demographics the way they hoped for. Some general questions about whether things are headed in a good direction or wrong track.”

If a poll doesn’t ask that basic information and starts off with a flurry of negative statements about one candidate, that’s likely a “push poll.” Unlike a poll that seeks to gather information about what voters think, a push poll is solely interested in influencing voters.

“Those are not legitimate polls,” Franklin said. “They’re just telemarketing calls.”

But defining “legit” when it comes to polling can be subjective. Not every pollster has the same objective because they’re working for different clients. And that shapes the way they ask their questions.

An academic poll like Marquette’s shares almost everything with the public, including their questions and details about their sample population. If their questions seem leading or biased, Marquette — and Franklin — will be scrutinized.

But when a pollster is working for a campaign, they may have different objectives in mind. Ulm said that might mean testing to see how voters respond to certain news about candidates, both positive and negative.

“Most of our work never sees the light of day,” said Ulm. “It’s a tool to try to understand the voters — where they’re coming from, their issues and their priorities.”

Tollaksen said campaigns use that information to shape their messages.

“That can come across as unbalanced, but it is for a very legitimate research purpose,” Tollaksen said. “It’s an attempt to try to gather information to understand what’s important to voters.”

The case for political candidates, universities or news organizations conducting polls is an easy one. It gives them at least a shot at predicting the future, and in the case of campaigns, a chance to try to change it.

For potential voters bombarded with polling calls, like Jaramillo, it can be a tougher sell.

“The first thing I want to do is thank her for taking polls. I wish more people would,” Tollaksen said. “And because she’s willing to take these polls is probably why she continues to get targeted with all of them.”

Seltzer said a published poll gives people a chance to see an unbiased picture of where political campaigns stand. They’re not possible unless hundreds of individual voters participate.

“Our industry, for the most part, relies on the kindness of strangers,” Seltzer said. “You don’t know us. We don’t know you. But we need something from you.”

Seltzer said it gives elected officials a chance to see what voters want.

“We know that candidates and elected officials pay attention to polls. So this is kind of a support for democracy, it’s one way that your voice can be heard,” Seltzer said.

This story was inspired by a question shared with WHYsconsin. Submit your question below or at wpr.org/WHYsconsin and we might answer it.