The coronavirus caused massive disruptions to education for both teachers and students across Wisconsin.

Before the school year ended, teachers had to deliver their lessons to students who might not have computers, internet access or even the time and space to work on lessons — all while the various stresses of a global pandemic, from fear over infection to economic anxiety as their parents and family members lost jobs, pulled at students’ attention.

“Unfortunately, at home, they aren’t really participating like they were in the classroom,” said Joe Menting, who teaches seventh grade social studies at Milwaukee’s Burbank School. “At this point, the only way we’re going to get them to engage is if it’s something they’re truly interested in.”

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Even before schools closed, Menting’s classes started with a discussion of CNN 10, a program that goes through the day’s top headlines. When classes moved online, he and his seventh graders switched to watching the show via Google Meet, and talking about their own experiences and questions about the news.

When protests and demonstrations erupted in Milwaukee at the end of May following the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis, Menting recognized it as a historic moment.

As a social studies teacher, he saw it as a way to get his students engaged with their city’s history, while also encouraging conversations about issues like police brutality and racial profiling, that affect many of his students.

One student, Rondall Ward Jr., took Menting’s lessons and ran with them. The 13-year-old has delved into news segments, history websites and his own personal experience to research the country’s history of racism and police brutality.

“What got me started on this was seeing all of my culture get hurt, brutally beaten, killed even, over our skin tone,” he said. “I thought it was really wrong because we didn’t choose to have this. We shouldn’t be scared to walk down the street every day.”

He turned some of that research into his “passion project” for Menting’s class, a presentation students can do on a topic they choose — in Ward’s case, police brutality.

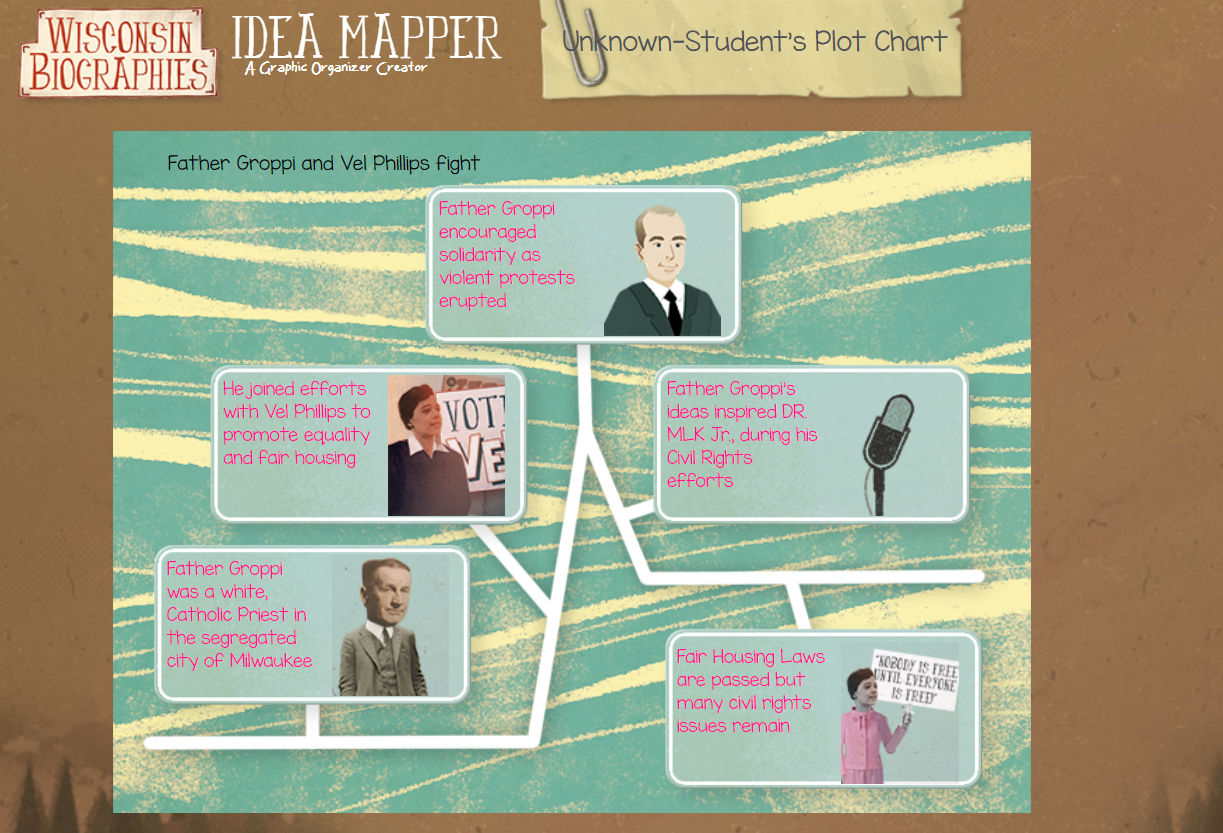

Menting worked to tie today’s protests into Milwaukee’s history for his students — especially the 200-day open housing protests led by barrier-breaking politician Vel R. Phillips and Father James Groppi in 1967 and 1968.

“I was hoping that introducing Father Groppi and Vel R. Phillips and their success with the Fair Housing Act would lead these students to understand that this marching will lead to progress and is significant in history — just like it was way back in 1967,” he said.

Room 33 will be learning about Vel R Phillips & Father Groppi in tomorrow’s lesson https://t.co/A6TyjxcqVV

— Joe Menting (@jmenting608) June 2, 2020

For Ward, comparing videos and photos of the protests in the 1960s to today’s marches has also meant understanding that in some ways, very little has changed.

“The difference is, one is in black and white, one is in color,” he said.

Like many of his peers, he turned to social media to share some of what he learned. He’s posted lists of the names of people killed by police to his Instagram and Snapchat stories, as well as graphics showing the disparities in how people of different races are treated by the justice system.

Though he hasn’t participated in any protests yet, Ward said he plans to.

“I would love to be there,” he said. “I would love to show my support over the whole movement.”

Many older students have filled out the crowd in protests across the Milwaukee area, raising their voices against police killings.

Chanese Knox, a recent graduate of Greendale High School in the Milwaukee suburbs, participated in a June 3 march at the Islamic Society of Milwaukee that was itself organized by two teenagers and former Milwaukee Public Schools students. It was Knox’s second march, and the lead-up to an even more hands-on approach — the 17-year-old organized her own march at her high school for later that week.

“I’m hoping that the world will see that this is not going to stop, and we demand justice,” she said.

Teachers were also talking about the protests, and their context, with younger students in Madison, the other epicenter of Wisconsin protests in the aftermath of Floyd’s death.

Elizabeth O’Leary is a special education teacher for second-graders at Frank Allis Elementary. She said when they started talking to students about the protests, it helped to have already gotten the ball rolling about civil rights and racism during February’s Black Lives Matter Week of Action. Each day, they covered a different topic using age-appropriate lessons guided by the national organization, including how to be queer-affirming when talking about Black Lives Matter and the history of black communities.

“It does seem intimidating to talk about this with second-graders, but at the same time, if we don’t start talking about it at a young age, then those biases and the systemic racism we know is a part of education, those are going to take hold instead of the anti-racist work that we’re trying to do,” said O’Leary.

They also talked about famous figures from the civil rights movement throughout the year, like Ruby Bridges, who desegregated an all-white New Orleans school when she was around the students’ age.

“I think we’ve built this knowledge throughout the year,” she said, “and because we were able to do that, we’ve been able to send a message now of our support for our black community, and the black community throughout our country and in Madison, too.”

Still, O’Leary acknowledges a fault in her own school that’s reflected in the rest of the state’s schools.

“We are a staff of mostly white women,” she said.

In Milwaukee, where the majority of students are students of color, only 4 percent of teachers are black or Latino. Outside of Milwaukee Public Schools, it’s 2 percent of teachers, compared to 16 percent of students. That means in many cases, the teachers talking to their students about the country’s history of and current struggles with racism haven’t experienced it as directly as many of their students.

“I’ve been doing more listening, because that’s what’s important,” said O’Leary. “We need to lift our black voices, and then I need to be standing next to them or behind them, supporting them in any way I can.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.