As Milwaukee County prepares to build a new secured residential care center for the youth offenders currently sent to Wisconsin’s troubled youth prisons, Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake, officials are turning to New York City for inspiration.

A group from Columbia University’s Justice Lab visited Milwaukee this week to share what they learned when the city went from an institution-based to a community-based juvenile justice system. New York City hasn’t sent any new offenders to state youth prisons since 2016.

Vidhya Ananthakrishnan, director of youth justice initiatives at the Columbia Justice Lab, said Wisconsin should view the crisis at Lincoln Hills as an opportunity to redefine how youth are rehabilitated.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“There is a moment right now to really seize this opportunity,” Ananthakrishnan said. “There has been a lot of focus in Milwaukee on how new facilities might look locally and how to move the kids from the state to the county. One of the questions in New York we asked was do these kids need to be incarcerated and is that the right thing for us to be doing. Ultimately, we decided what’s best is for kids to be treated at home and in their own communities.”

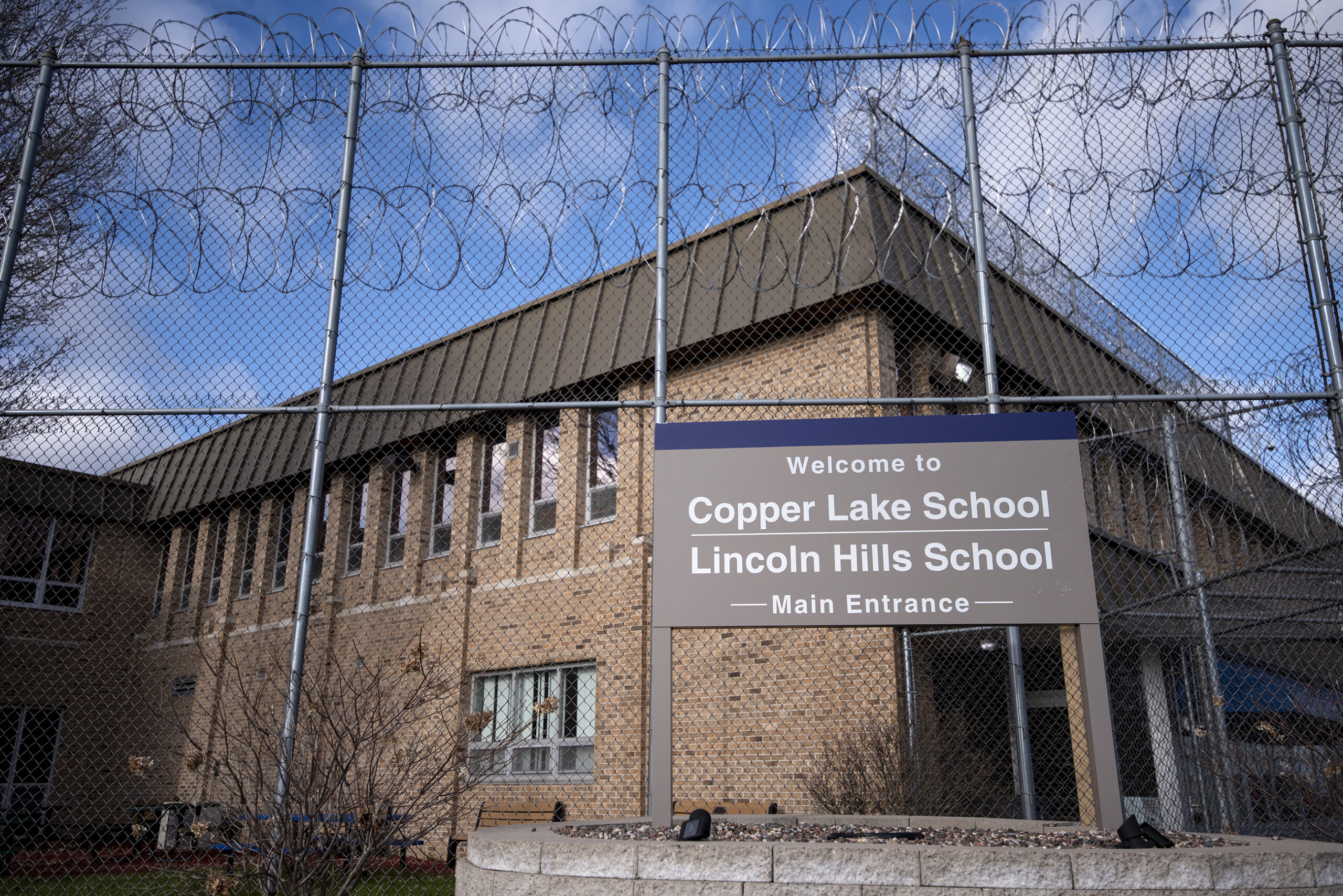

Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake, which are located north of Wausau, have been plagued by allegations of inmate abuse and neglect for years. A January report from a court-appointed auditor found Lincoln Hills and Copper Lake are still using pepper spray and solitary confinement to discipline inmates.

A law to close the state’s youth prison by 2021 was passed unanimously by the Legislature in 2018 and signed by then-Gov. Scott Walker. Gov. Tony Evers has delayed closure by up to two years, saying that is how long it will take to build the new facilities.

The juvenile jails will be replaced by two state-run, “Type 1” juvenile correctional facilities for youth convicted of serious crimes or those who were tried and convicted as adults. There will also be county-run residential centers for youth who have committed less-severe offenses that will include programing and workforce training.

The state Department of Corrections hasn’t said how many county-run centers there will be or where they will be located. Milwaukee County is the only location that has been announced as a site. According to the county, about 65 percent of youth in the state prison are from Milwaukee County.

Milwaukee County Executive Chris Abele said keeping children closer to home and providing evidenced-based programing will help reduce recidivism.

“When Milwaukee gets a chance to rewrite the chapter that started with Lincoln Hills we don’t just do a little bit better, we are going to try and set the new model and maybe 25 years from now, other cities are going to say, ‘Alright, how do we become Milwaukee?’” Abele said.

In the mid-1990s, approximately 3,800 children in New York City were convicted annually and sentenced to one of three dozen large, state or privately-run youth prisons. Many were in Upstate New York. Most of the children were poor and black or Latino.

“New York was probably where Milwaukee was 10 years ago,” Ananthakrishnan said.

A high-profile death of a young boy from the Bronx who was at one of the youth prisons called into question everything that was being done, Ananthakrishnan said.

“It started a conversation in New York similar to what is happening in Milwaukee and Wisconsin now,” she said.

In 2011, the Milwaukee County Health Department launched a youth justice reform program called Project Rise. One aspect of the program is to educate the public about the trauma many of Milwaukee’s youth experience and the importance of family, the community and school to a young person’s overall health.

Abele said New York has been one of several models Milwaukee County has studied.

“In addition to treating their youth more humanely, drastically lowering recidivism and saving money, (New York City) has done the right thing morally,” Abele said. “We want to bring our youth closer to home, offer them better programing and make it easier to finish school and reintegrate back into the community.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.