The city of Milwaukee is on pace to break its homicide record again this year.

The county’s medical examiner, in a tweet early Monday, said there were five homicides over the weekend, and 18 in the last half month. That includes three separate shootings late Saturday and early Sunday on the heels of three shootings near the Deer District after Friday’s Milwaukee Bucks playoff game at the Fiserv Forum.

At a press conference over the weekend after the Deer District shootings, Milwaukee Mayor Cavalier Johnson advocated for punitive and preventive measures in response.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“If somebody hurts somebody in this community, if they cause death, if they cause harm, if they cause destruction, they should be held accountable,” Johnson said. “Before somebody gets to the point where they have a gun and they’re upset, and their tempers go off and they decide to shoot in a crowd full of people, you’ve got to think about whether or not those folks should have access to a gun in the first place.”

Public data from the medical examiner’s website counts 81 homicide victims in Milwaukee County so far this year. That’s up from 65 deaths at this point last year.

The state as a whole saw more than 300 homicide deaths last year, up 70 percent from before the coronavirus pandemic. According to the state Department of Justice, Milwaukee County alone accounted for nearly two-thirds of those deaths.

Reasons behind the increase

Law enforcement experts say the reasons for the ongoing increase in homicides vary from too many guns on the street to the ongoing affects of the pandemic to human desperation.

Jamaal Smith is the community violence prevention manager for the city’s Office of Violence Prevention, which has created a Blueprint for Peace — an in-depth investigation of the prevalence of violence, risk factors, preventative measures and goals and strategies for the city to follow.

Smith said levels of anger, pain and trauma that already existed prior to the pandemic have been exacerbated by it.

“It’s generational trauma, in addition to current trauma in its current context,” Smith said. “The majority of those who are perpetrators of gun violence have in some form been directly or indirectly impacted by that violence as well … That’s why they always say ‘hurt people hurt people.’”

Smith said the onus doesn’t lie only with the people in communities inequitably affected by violence.

“That also requires accountability on our policymakers, whether that’s at a municipal level, county level, state level, federal level,” Smith said. “Making sure that there are policies being created that address the social determinants of health, and that they’re being addressed at an equitable level, knowing that there are some communities that are at a disadvantage more than others.”

But, Smith said communities do have a role to play in reckoning with the issues at hand.

“Yes, we are the Office of Violence Prevention, but there are six of us in the office,” Smith said. “Every last person of the city has to be responsible from your block in your neighborhood, to your church, to your school, to your place of employment or your place of worship period … Everyone is responsible for violence prevention, right? Everybody’s responsible for what this city looks like.”

The role policing plays

In September, then-Acting Police Chief Jeffrey Norman said detectives were struggling to keep up with caseloads.

Milwaukee Alder Robert Bauman said the city’s police “are pretty much hamstrung” because of financial constraints. City officials have, in the past, advocated for an increase in shared revenue, or state funding for local governments, but to little avail.

“We can’t add police,” Bauman said. “We’ll be lucky to maintain police … We really need help from the state of Wisconsin.”

Jordan Morales, vice president of the Sherman Park Community Association in the city’s West Side, is advocating for more policing in the short term and more economic development in the long term.

“I think everybody wants to address the root causes, but the problem is, you’re talking about, you know, decades, several decades of work, and we’ve got to deal with some homicides now,” Morales said. “What I see my neighbors asking for is more policing. They want to see it equitable in the sense like it’s not targeted, you know, they’re not harassing people just walking down the street … but I think there’s lots of legitimate crimes happening on the streets every day that can keep the police busy.”

Johnson said the issue goes beyond police.

“This is not just a policing problem, this is a community problem,” the mayor said. “If somebody pulls a trigger anywhere in Milwaukee, and somebody sees something happening, then folks have got to speak up.”

Addressing inequities

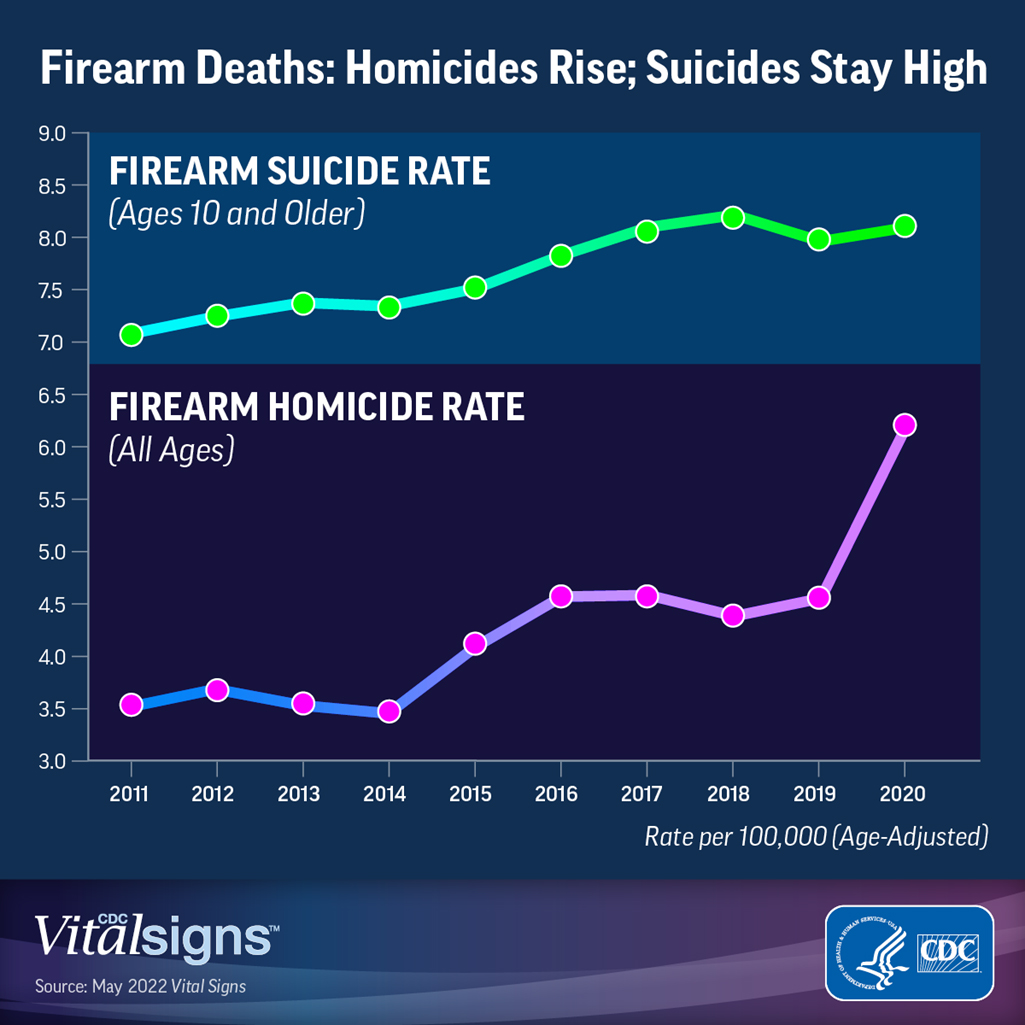

At the national level, the firearm homicide rate rose 35 percent in 2020, reaching its highest level in more than a quarter-century. That’s according to research released last week by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which found 79 percent of 2020 homicides involved guns.

That research noted Black people are particularly affected both in terms of the overall gun homicide rate and increases in gun homicides. It also found higher rates and increases in areas with higher levels of poverty.

“Long-standing systemic inequities and structural racism may contribute to unfair and avoidable health disparities among some racial and ethnic groups,” the research reads.

Smith said conflict resolution and investing in communities have roles to play in resolving the problems that lead to gun violence.

“We are no longer in a position to operate from an individualized lens,” Smith, with the Office of Violence Prevention, said. “We have to figure out the best ways of coexisting and collaborating, from grassroots to policymakers.”

Looking longer-term, Johnson said paying a living wage and offering summer programs for youth could help in dealing with instability.

“If we can have stability in people’s lives, that creates stability in families, and if there’s stability in families and stability in neighborhoods, it changes the way that people interact when they’re on the streets or whether they’re in the school,” Johnson said.

He said he wants to avoid the domino effect of shootings impacting the city’s economy and, in turn, impacting the city itself and the safety of the people in it.

“We can solve this,” Johnson said. “We have the ability to do this. We just need the will.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.