Daniel Bergner felt frustrated and helpless back when his brother was diagnosed as having bipolar disorder. Bergner and his family were told that institutionalization and medication would be crucial to keeping him healthy and safe. But Bergner had his doubts.

“It wasn’t that I was rejecting all of what our parents said, and all that the psychiatrist said, but it just seemed too simple, too straightforward for this thing that is our minds, ourselves, our psyches,” said Bergner, explaining what lead him to write a book about the subject, “The Mind And The Moon: My Brother’s Story, The Science Of Our Brains, And The Search For Our Psyches.”

“Top and elite researchers told me again and again, ‘We haven’t made progress in our psychiatric medications in half a century.’ But meanwhile, practitioners are doling out psychiatric drugs at increasing rates,” said Bergner, speaking with Charles Monroe-Kane for Wisconsin Public Radio’s “To The Best Of Our Knowledge” for the “Going for Broke” series.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

As prescriptions rose, so did the number of psychiatric diagnoses, including a 40 fold increase in bipolar diagnoses over the previous decade.

Bergner decided to report out other possibilities for his brother’s healing, and also new chances for his brother’s — and thus his own — life.

“I’m talking constantly with really compassionate, thoughtful psychiatric researchers. And yet somehow we’re missing the individual in the way we think about health,” Bergner said. “We’re not seeing the human being in a full way.”

This transcript was edited for clarity and length.

Charles Monroe-Kane: What was it like growing up with your brother? What’s he like?

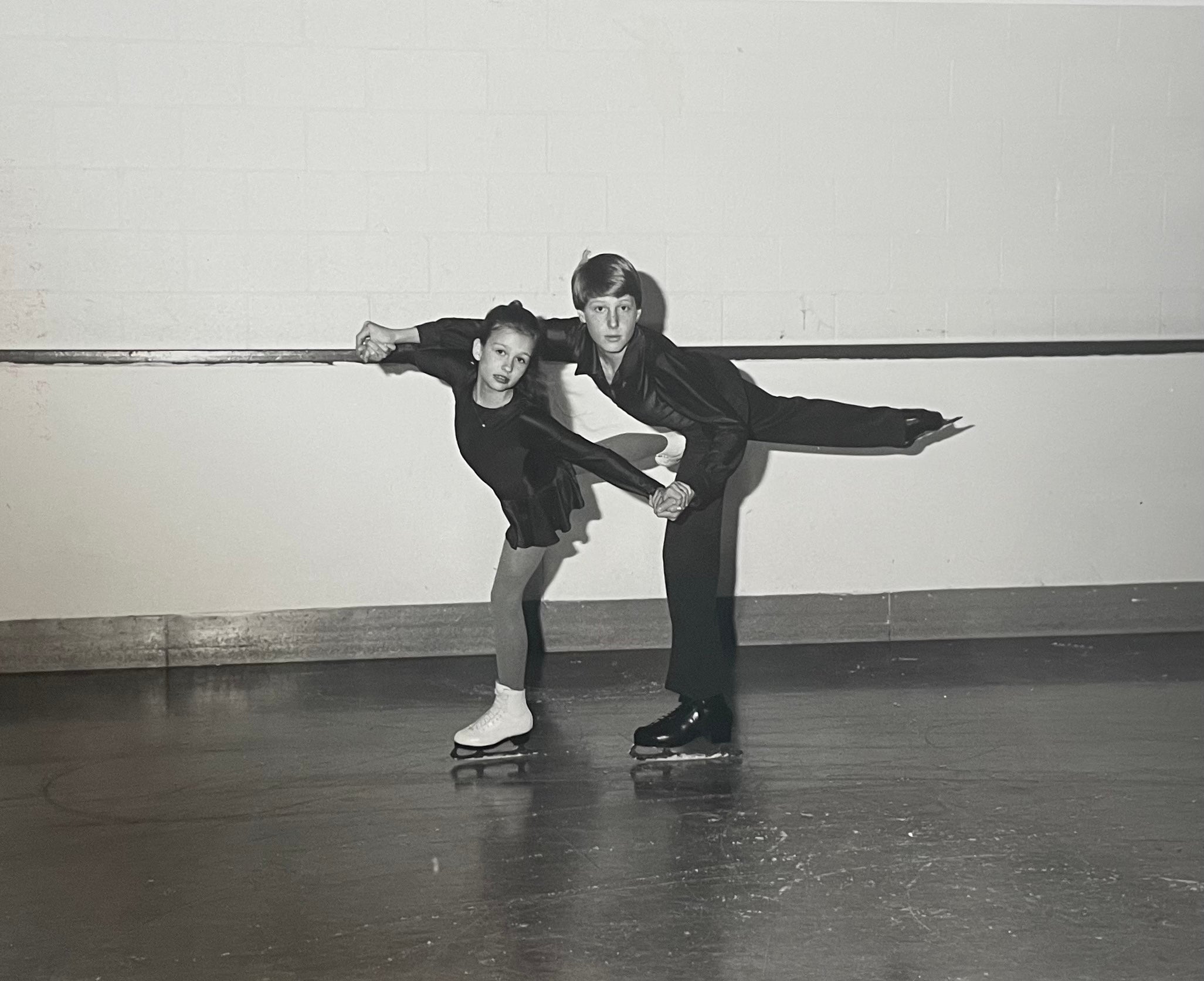

Daniel Bergner: Amazing musician. Really creative artist. Also a dancer, when he was young. And ambitious.

The side effects of the drugs prevented him from playing at the level that he was used to and with the nuance that he was used to. So a few years down the line, after hearing what the psychiatrists were telling him, he went off the medication, against advice.

There were dark moments. He was arrested. He was put back on a locked ward. He was homeless for a while. And that was a really, really trying time. But the truth is, flash forward, he’s lived a really flourishing, meaningful life over the past decades. So that in itself raises questions about that doctrine that said: take your medication, here’s your diagnosis, here’s who you are permanently.

Yeah, there was no permanence to this.

CMK: When I was young, I was diagnosed with schizophrenia, later diagnosed as type one bipolar. Somehow that was a celebration.

I have taken so many meds, Daniel, like just boatloads of combinations of meds. I’ve had so much therapy, so much psychiatry. I’ve been hospitalized a number of times — unfortunately, some of them not voluntary.

During all that, I would go to group therapy, and I would say, I love group therapy. I find it to be powerful. I find it to be useful. But the folks in my group therapy (now) — they’re a mess. And not just a mess mentally. I mean, their lives are a mess. They’re often just divorced, addicted, but also a lot of them are on the border of homelessness. One person is homeless. They are 40 years old and still living with their mom. One woman selling her body.

When I observe them and I observe their mental illness, the side effects and how it affects them economically is worse than the mental illness.

DB: Right. And indeed, statistics will completely back you up, as you probably know. So about 30-60 percent of those who are prescribed antipsychotics walk away from them. Conventional psychiatry would say that’s because they’re disorganized. That’s because they don’t acknowledge they’re ill, etc., etc.

I want to say if 30-60 percent of people are walking away from a treatment that’s supposed to help them, maybe we ought to look at this as they’re voting with their feet and on balance — they’re making a rational choice.

Now, again, you probably know this all too well, if you’ve got that diagnosis of schizophrenia or anything on that psychosis spectrum, practitioners are likely to doubt that you can make a rational decision. But over and over, what I found is (that) even when people are in crisis — even when they are engulfed in an “alternate reality” — if I’m willing to sit there and listen, I’m still able to connect.

We are failing repeatedly, constantly, to just acknowledge that there’s much, much more communication possible than mainstream psychiatry acknowledges. And that’s when people are in their most challenged place.

CMK: I want to go back to your brother, if you don’t mind me asking about him again. There must have been a time where he needed to be put away — it was serious, everybody in the family knew it. Now that you can observe that back in time, what do you think he needed?

DB: He and I talk about that all the time. I think he would say he needed someone who wouldn’t completely discount the ideas that he had, who would slow down and listen. And he actually, ironically enough, found this the second time he was locked up in a very unlikely place — he was in a state hospital, (the) worst caricature of the decrepit state hospital where people are forgotten — but he actually ran into a psychiatrist there who urged him to go back on medication (but) also had some things to say that let my brother know that he was heard.

CMK: There’s a moment in your book where you are with him and your brother on a ferry and he starts dancing. It’s like he’s already gone through a lot of things. And I read that like three times in a row. Do you know what I’m talking about? Could you read that?

DB: Yes.

“The impact of the rough water against the bow created a steady, emphatic beat, and above that the engine delivered not only a churning rhythm, but something bordering on a melody, deep and ancient, like a Gregorian chant. It was a small part of my brother’s gift that he both heard, at swelling intensity this music of water and machinery and allowed himself to be inspired and electrified by it. His body responded with a physical, visceral version of a child’s wonder as she holds a conch shell to her ear and listens to its elemental communications for the first time.

“He stood on the lowest deck, near the front of the cars and the slung chains, as the boat’s combination of Gregorian choir and pounding drum surged through him. He lifted one foot to knee height, then leapt high off the other and landed on the first foot so that there was a simultaneous vaulting and transferring of weight, followed by a reversal and more repetition back and forth, melded with the strivings of his torso and arms, amounting to movements at once, airborne and sinuous. To the few passengers who watched from their cars, his mix of military jumpsuit and elfin shoes may have looked odd, compounding the oddity of his dancing, but all of this strangeness was countered by the broad solidity of his body and by his resistance to the sporadic lurching of the boat, which should have pitched him off balance and made him grab at the chain poles or brace himself against a car, but never did. He hung in the air, stomped his heels on the steel deck, sprang from side to side, spun, and elevated again, athletic, animalistic, ethereal, impelled by the pulse of the water and the echoes of medieval worship.

“And soon he was in a psychiatric ward, with a heavy dose of Haldol seeping into his brain.”

CMK: I think that when I read the book, when I realized you loved your brother — that’s beautiful. But also, I think you were celebrating people who are mentally ill. You spent so much time with your brother writing this book, clearly. What does he think of it? What did he think of a passage like that?

DB: Well, first, thanks. I’m glad we connected over that passage because it’s so important to me, important to my brother. I think he appreciated that. I was trying to see, feel, hear my way into his way of seeing and feeling and creating. And he was creating.

He was outside the bounds of social comportment. I mean, he was dancing on a ferry deck but there were at least a couple of times when he did this, and I was there for one of them. And I remember, I’m sadly much more conventional, that a part of me was a little embarrassed, but a part of me was kind of in awe because he’d been inspired. And I was just a bystander to that inspiration.

CMK: I know this is a dangerous question, and I’ve been asked this question a number of times in my life. I’m very manic inside of my mental illness, which means I can get a lot done in the world, even though I’m tired at the end of it. Is mental illness a gift?

DB: Well, I wouldn’t even use the word “illness.” I’d go a little more radical. One of the things that shook me was the frequency with which some psychiatrists, certainly not all, were unable to see that.

CMK: Amen.

DB: I’ll give you an example. I was invited to a little kind of salon soiree and, you know, it was all very ego affirming for me. We were going to talk about one of my books and it happened that there were several psychiatrists at that table. And this psychiatrist said rather proudly, “I almost never see a patient for whom I don’t prescribe medication.”

And so I said, let’s take Hemingway just for an example. I know this is a little sophomoric and simplistic, but here’s the question: You can have a couple of the greatest novels in American literature and some of the greatest stories in American literature, but have your patient kill himself at age 60. Or you can medicate that patient — because a lot of people think retrospectively Hemingway was bipolar — from the time he’s 20, but you are likely going to sacrifice those great works of literature. He’s not going to quite produce at that level.

And what struck me was the psychiatrist didn’t even pause. He just said, “Of course I would medicate.”

And I’m thinking the opposite. I’m right around that age. I think (if) you give me that tradeoff, I will end sadly and devastatingly as the tradeoff for having written art at that level.

Now, again, this is simplistic, but it just shows you something about that worldview that wants to control. And control and creation are kind of opposite forces.

CMK: What do you see in the future for all this?

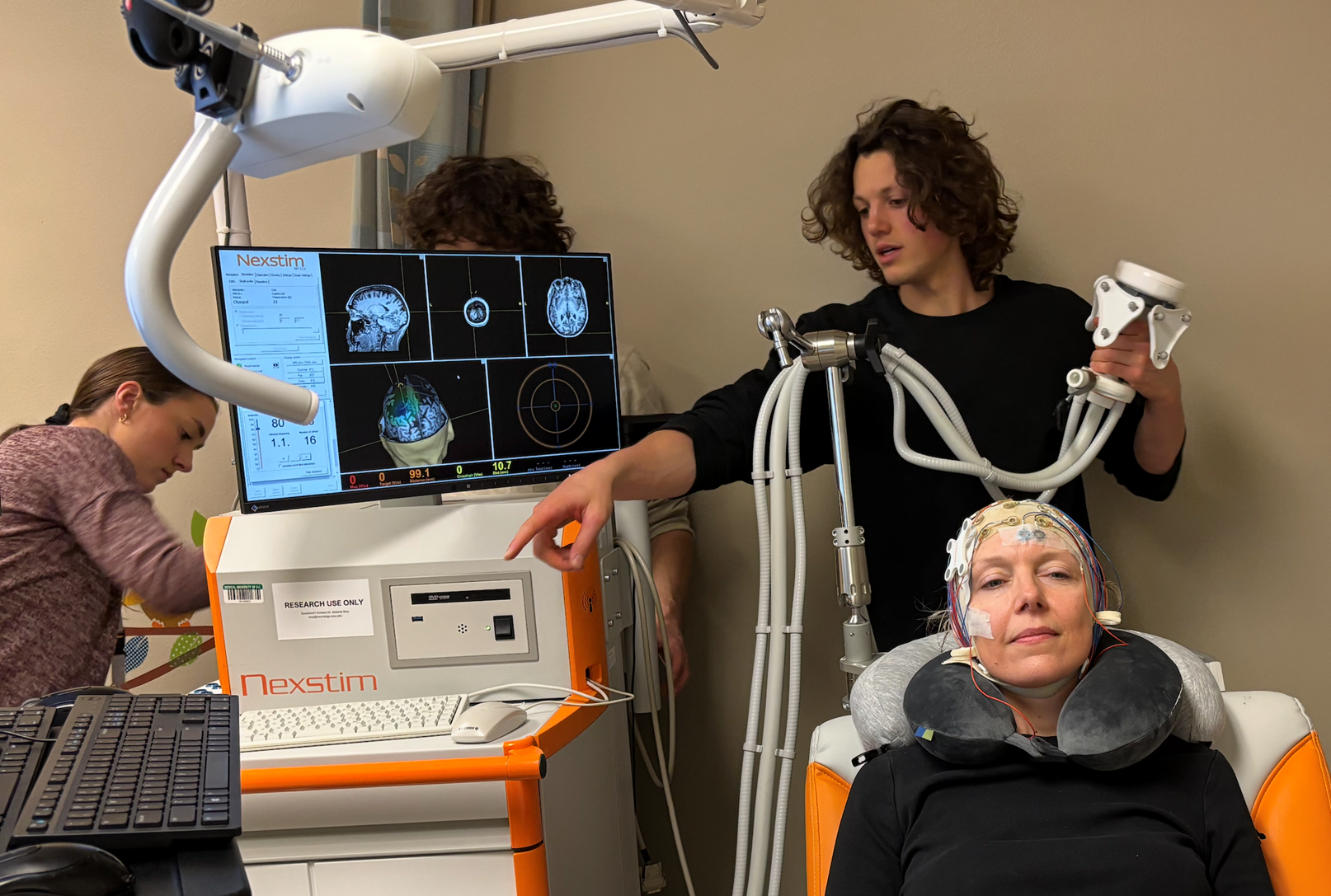

DB: I’m somewhat optimistic because of the frequency with which I heard neuroscientists acknowledging the limits of our understanding and the limits of our medication. My mind goes to recent psychedelic research and into a lesson I think it holds.

Recently, my newspaper — almost always perfectly fact checked, but not quite always — just ran a story trumpeting the psychedelic revolution and it cited several large recent studies. Only one of those studies was successful. The other was a total failure. It had no significant difference in the psychedelic response to the SSRI response. But the one that was successful had combined the psychedelic with a very particular kind of extensive therapy.

So I went so far as to read the therapy manual, (which) lays out therapy that calls for a sense of oneness, for a sense of connection with one’s surroundings. (It) calls for a deeper and expansive sense of self.

One of the people associated with this work said, “Yeah, the psychedelic can help you, but like all other magic bullets, it’s not going to strike its target on its own.”

The magic is in using that chemically-aided moment to get you to a place where you’re able to put yourself within something larger. And if I think about the stories that are triumphant in this book, that is what they’re able to do.

How we live is indelibly intertwined with the care and empathy we give to each other.What if we put care into helping Americans find homes and into how we build dwellings, into keeping their bodies and minds sound, and how they find meaningful and well paid work? In a three part series, “To The Best Of Our Knowledge” and the Economic Hardship Reporting Project bring you real life stories about economic struggle in our time, as well as ideas for solutions. Learn more about the series at ttbook.org/goingforbroke.