This might be the year for ticks. Or cicadas. But not so much for mosquitoes.

With a long and cold spring earlier this year, mosquitoes didn’t have as much of a chance to ramp up in numbers, said Lyric Bartholomay, a professor in the department of pathobiological sciences at the University of Wiscconsin-Madison.

“I don’t have complete evidence of that, but that’s what I suspect,” she said.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

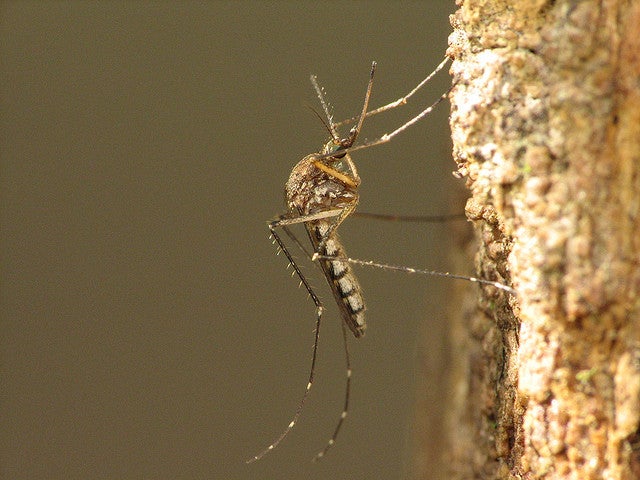

Wisconsin is home to 56 species of mosquitoes, though many don’t suck on or bother humans. And, of the species that do suck on humans, it’s only the female — they need blood to grow their eggs.

Mosquitoes are pesky, no doubt, but Bartholomay said they’re also integral to the health of local habitats, specifically to birds, bats, ducks and other species that feed on them.

In fact, Bartholomay said that in places where mosquito larvae are well controlled, birds get less protein, which then impairs their own reproduction.

“It’s very likely that (mosquitoes are) really important in a way we under-appreciate,” she said.

Climate change is posing another challenge for mosquitoes, as with most other species. If climate change leads to more frequent and heavier rainfalls, mosquitoes could be negatively affected by heavy rains washing away their habitats and killing them in larval stages.

“And then, if it’s followed immediately by a drought, that also can impact whether there’s sufficient habitat for them to grow and develop,” she said.

Despite their value to other species, efforts are taken each year across the state to manage the mosquito population, though it’s pretty patchwork, Bartholomay said. There’s no state-based system for mosquito abatement.

Mosquito management done at the community level must comply with regulations from state agencies such as the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Those tactics include biological controls such as Bti, a mosquito larvicide that destroys the guts of larvae that eat it.

Chemical controls are used on adult mosquitos, but those are sprayed at night when mosquitoes are out to limit impact on other insects that are active during the day, such as pollinators.

Bartholomay said she’s not familiar with regulations that private companies have to comply with when contracted to spray a specific area. She said if you’re thinking of hiring a company for this purpose, ask what chemicals they use, and ask that they spray at dusk, when pollinators are no longer active.

There are other ways to at least protect your own skin from those mosquito bites.

She finds the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s search tool particularly helpful in finding the right product to keep mosquitoes at bay, with information about which repellent to use for specific lengths of time. You can also search by active ingredients or company names for products.

Bartholomay said that although citronella candles might smell good and might repel some mosquitoes with the flame and smoke, they’re really not that effective.

Getting people to understand the role of mosquitoes and how to keep ourselves and our communities safe is another passion for Bartholomay.

She does this by helping to run the Mosquitoes & Me Summer Camp in Iowa with colleagues Sara Erickson and Katherine Richardson Bruna, who each year pose a question to their campers: “If humans and mosquitoes had a battle at the end of the world, who would win?”

“Kids from all over have a role to play in public health and in the safety of their families,” she said. “We’d love kids to get more involved in knowing about mosquitoes and being change agents in their backyards.”

The campers learn about mosquitoes, ecology and disease, and create comic books where mosquitoes are either villains or heroes. Campers have even worked with Marvel Comics to turn Mosquitoes & Me into a comic book.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.