“It was a very good year” might be how Bob Dylan would describe how things went for him in the years 1965 and 1966. (Such an answer would also have a delightful double meaning, playing into Dylan’s current Frank Sinatra fixation.)

Over the course of those mid-’60s months, Dylan was on a creative run unlike any in music history. He was at the white-hot center of counter-culture fame and relevance while simultaneously managing a seemingly unyielding surge of landmark musical ideas. He appeared supernaturally charged with a kind of energy, every spark offered song ideas imbued with unrealized promise and begging to be turned into masterworks. And then he did so.

This period is the primary focus of “The Cutting Edge 1965-1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12,” a massive box set being released on Friday. (There’s a two-disc, six-disc and 18-disc versions of this compilation to service various levels of Dylanologists, from newbies to gonzo.) The box set attempts to cover the highlights (and in the case of the 18-disc set, every single recording session) of Dylan’s time in the studio from that climatic year. It shows in take after take — sometimes in painstaking detail — how inspiration, perseverance and surrounding oneself with sympathetic talent could turn great songs into world-shaking classics. While the box set offers many examples of how masterpieces were constructed, this compilation also brings fans perhaps the best song sketch in Dylan’s entire catalog.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

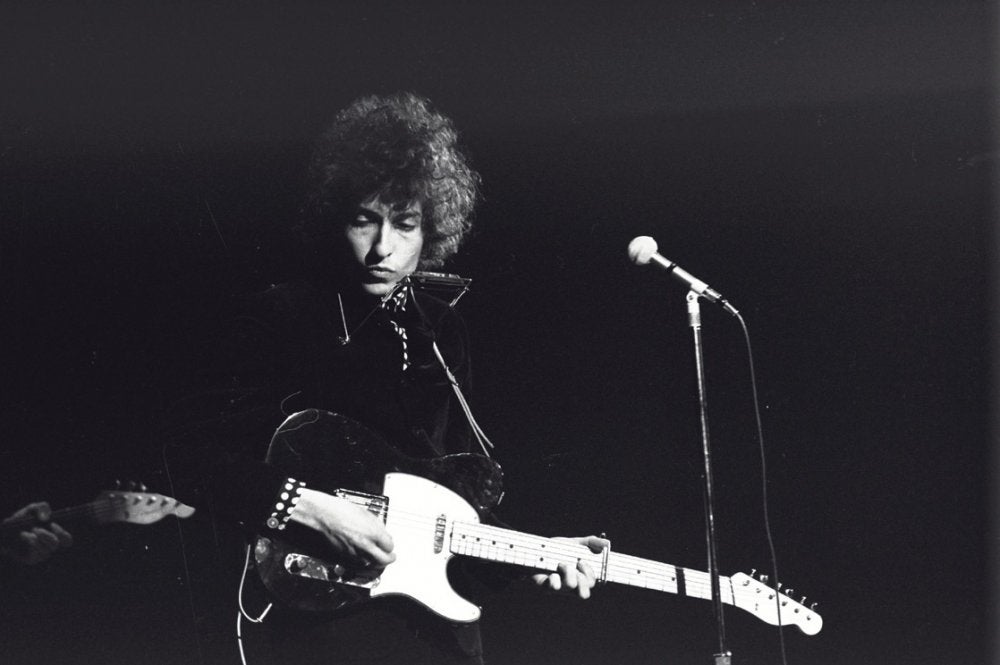

This portrait of an artist as a young man shows a songwriter constantly in fidgety motion. He’s literally drunk on his fame, but clear-minded in his commitment to push his creative impulses to new limits. On many levels, this was a whirlwind year for Dylan. He “went electric” by forswearing his destiny as the anthem-writing mouthpiece of the ‘60s folk movement to forge a new one as a fully formed, reflective songwriter and a pop star in a Telecaster-toting band. His musical sights squared on exploring new forms based on surrealistic, allegorical lyrics stitched to the sounds of R&B, blues and rock ‘n’ roll at full volume. That vision brought him to release three of his most seminal albums — “Bringing It All Back Home,” “Highway 61 Revisited” and “Blonde On Blonde” — and hook up with a troupe of Canadian road warriors, the Hawks (later famous on their own merits as the Band) to launch one of the most fantastic and infamous tours in pop music history.

And for those keeping score at home, Dylan was juggling a whole lot more that year besides the music. He was planning the release of a free-associating poetry book and a self-produced TV program documenting the aforementioned tour. According to various biographers, he was also experimenting with various high-powered street drugs, a series of high stakes but fleeting romances and then got married for the first time. “It takes a lot of medicine to keep up this pace,” he would tell a contemporary biographer.

All of this brings us to the unfinished “I Can’t Leave Her Behind,” perhaps the greatest, coulda-been-masterpiece in Dylan’s canon. (The fact that it will only be available on the 18-disc version of the box set is a mistake.) This song was the part of the many musical woodshedding sessions that Dylan conducted with guitarist and chief sounding board Robbie Robertson at various hotels around the globe during the tour. (The Dylan/Hawks tour began in the U.S., continued in Australia before concluding in Europe.) The pair, with two acoustic guitars, were ruminating on half a dozen works in progress in between their frantic touring and recording schedules. Rumors suggest that “I Can’t Leave Her Behind” was recorded in Glasgow, Scotland, but that is unconfirmed.

Luckily for posterity, this workshopping was recorded on film by D.A. Pennebaker and Howard Alk, who were documenting the end of the tour at Dylan’s behest. Their footage was later scrambled together into Dylan’s first attempt at high-art cinema, “Eat The Document.” The clip below, which comes near the end of “Eat The Document,” was the only record of this song’s existence until the box set’s release.

The clip starts with a very nearly bored Robertson plinking out the opening notes to “O Christmas Tree” before witnesses get the first of several jarring jump cuts that drop passersby into the most exquisite string of guitar chords.

The song is a sketch – barely a minute and 30 seconds in the film – but even Dylan-phobes couldn’t ignore that this idea is pregnant with promise. Dylan’s singing is soothing and the words are often slurred. If these are the real lyrics instead of just sounds to flesh out the melody, Dylan proves a compelling seducer even when he’s dozing off. He is rocking manically throughout and his unruly brown hair looks aflame. He looks like he hasn’t slept for a couple of weeks. The song’s mood is eerie reminiscent of the cool, somnambulistic romance ramblings of “Just Like A Woman,” but Dylan now sounds overawed by his muse and thorughly controlled by her.

As the guitar chords and country-style finger picking blend together, Robertson’s driving lead lines clear the way and beautifully accent Dylan’s elegant strums. When Dylan leads them into the song’s outro, the final chord progression is nothing short of perfection. A slight head shake and a grin that crosses Robertson’s face says it all before the screen fades to black.

And with that, “I Can’t Leave Her Behind” seemingly fell off the face of the Earth. With the U.K. leg of the European tour completed in May 1966, Dylan and the Hawks returned to the U.S. for a breather before a larger American tour commenced later in the summer. Dylan mostly retreated to his home in Woodstock, N.Y., while the Hawks wallowed in Manhattan. No recording sessions are known (although there are stories of Dylan and company helping demo material for a young Carly Simon).

Ultimately, a motorcycle crash — one that’s still ripe for assorted conspiracy theories 50 years later — scuttled the tour, book, TV program and any serious work on a new album for more than a year. The crash marks a definitive end to Dylan’s wild-eyed “electric” period and the beginning of an important transition of his creative life. Never again would he so boldly mix musical forms and challenge venerated conventions. For the rest of his career, Dylan has been a conservator of American roots music and ideal student of forms rather than an iconoclastic musical revolutionist.

When Dylan reentered a recording studio more than a year later, “I Can’t Leave Her Behind,” didn’t catch the train and was left half-formed. (Former Pavement frontman Stephen Malkmus tried and failed to flesh out the song for the soundtrack for the 2008 art-house Dylan biopic, “I’m Not There.”)

As it stands, fans will never know if the follow up to “Blonde On Blonde” as conceived before the motorcycle crash would have taken Dylan further still or become a “Magical Mystery Tour”-like derivative work. Regardless, “I Can’t Leave Her Behind” leaves the hope brightly dangling. It was a very good year.