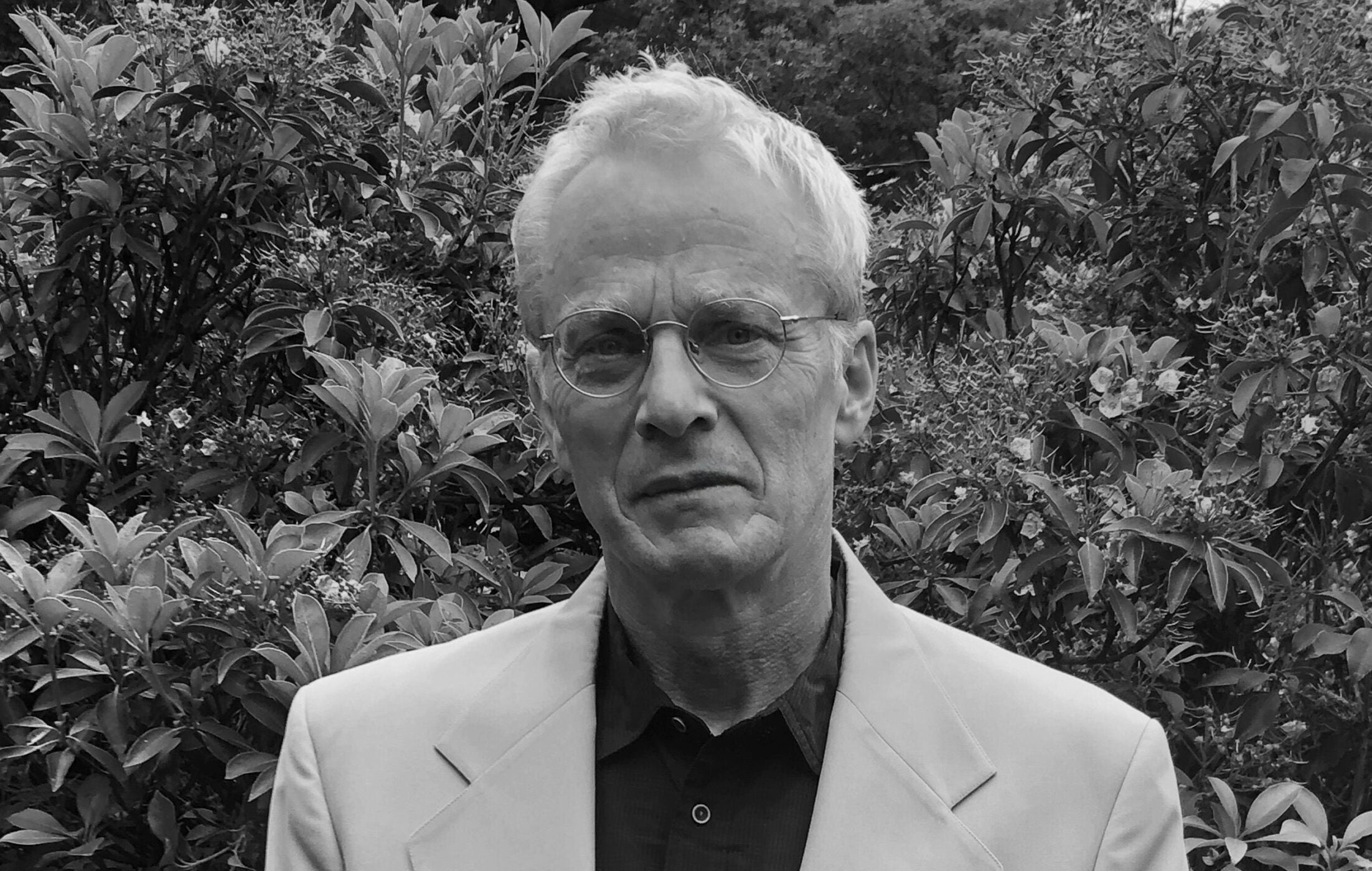

It’s a cliché that a genius’ work is often only recognized after death, but this will surely be the case when history renders its final assessment of maverick jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman. His life’s work was anything but a worn-out cliché.

Coleman died of a heart attack on Thursday in New York. He was 85 years old.

For nearly seven decades, Coleman was jazz’s most stubbornly dedicated trailblazer, fringe philosopher and proponent of the music’s untapped potential for invention. The scope of Coleman’s work knocked down barriers — both real and imagined — for many of jazz’s most pivotal figures in the mid-20th century and mapped out a sonic course that many of today’s players still haven’t stretched beyond. Such was the impact of Coleman’s work that his influence extended beyond jazz circles and he enjoyed famous fans in the pop, rock and avant-garde classical music realms. He was the fountainhead and inspiration for generations of stylistic renegades.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Born in Texas in the 1930s, Coleman came of age in R&B and blues bands in the South before earning a spot as an alto saxophone sideman for many journeyman jazz performers during the height of the bebop era. By the late ’50s, however, Coleman struck out on his own and sought to explore many of the ideas that he couldn’t explore in more conventional gigs.

Those concepts exploded on the jazz scene at a time when bebop had already solidified its hold on most jazz musicians of the era. Coleman’s two landmark albums, 1959’s “The Shape Of Jazz To Come” and 1961’s “Free Jazz,” had the effect of an atomic blast that permanently shook bebop’s hold on the music and marked the definitive end of that epoch (if not that sound.)

Coleman’s songs and performances were brash and revolutionary in how they turned bebop orthodoxy on its head and transformed the music into a live wire that offered excitingly new, complicated and abstract sounds and forms.

As a player as well as a composer, Coleman sought not to simply deconstruct or upend many of jazz’s reigning strictures, but to break through artificial walls and make undiscovered connections to other genres and compositional ideas. His vision left few things in the music as sacred, challenging traditional concepts of melody, harmony, rhythm, structure, instrumentation and musical proficiency. (Eventually, Coleman added his own screechy, sawing violin playing to his arsenal of sounds.)

Like the Jackson Pollack painting that adorns “Free Jazz,” these sounds could be wildly abstract. The music was aggressive, sometimes cacophonous, as sounds and melodies collided and coalesced. Such was his headstrong reputation, however, that many of Coleman’s songs were never acknowledged for their compositional consistency and the music’s lyrical qualities.

Meanwhile, Coleman was aided in his mission by various ensembles of sympathetic musicians. These groups yielded not only fellow revolutionists, but later acolytes like trumpeters Don Cherry and Freddie Hubbard, bassist Charlie Haden, guitarist James Blood Ulmer, drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson and bass clarinetist Eric Dolphy. These musicians, even if they adopted more mainstream stance to their own music, nevertheless evangelized many of the key points first extoled by their mentor.

Although Coleman’s music championed a kind of musical freedom, that liberty came with a price. Mass audiences were often cool to his experiments and his defiance offered few compromises that are commonplace with traditionalists. Coleman wanted to communicate musically with the audience, to challenge the listeners, but it was always on his terms.

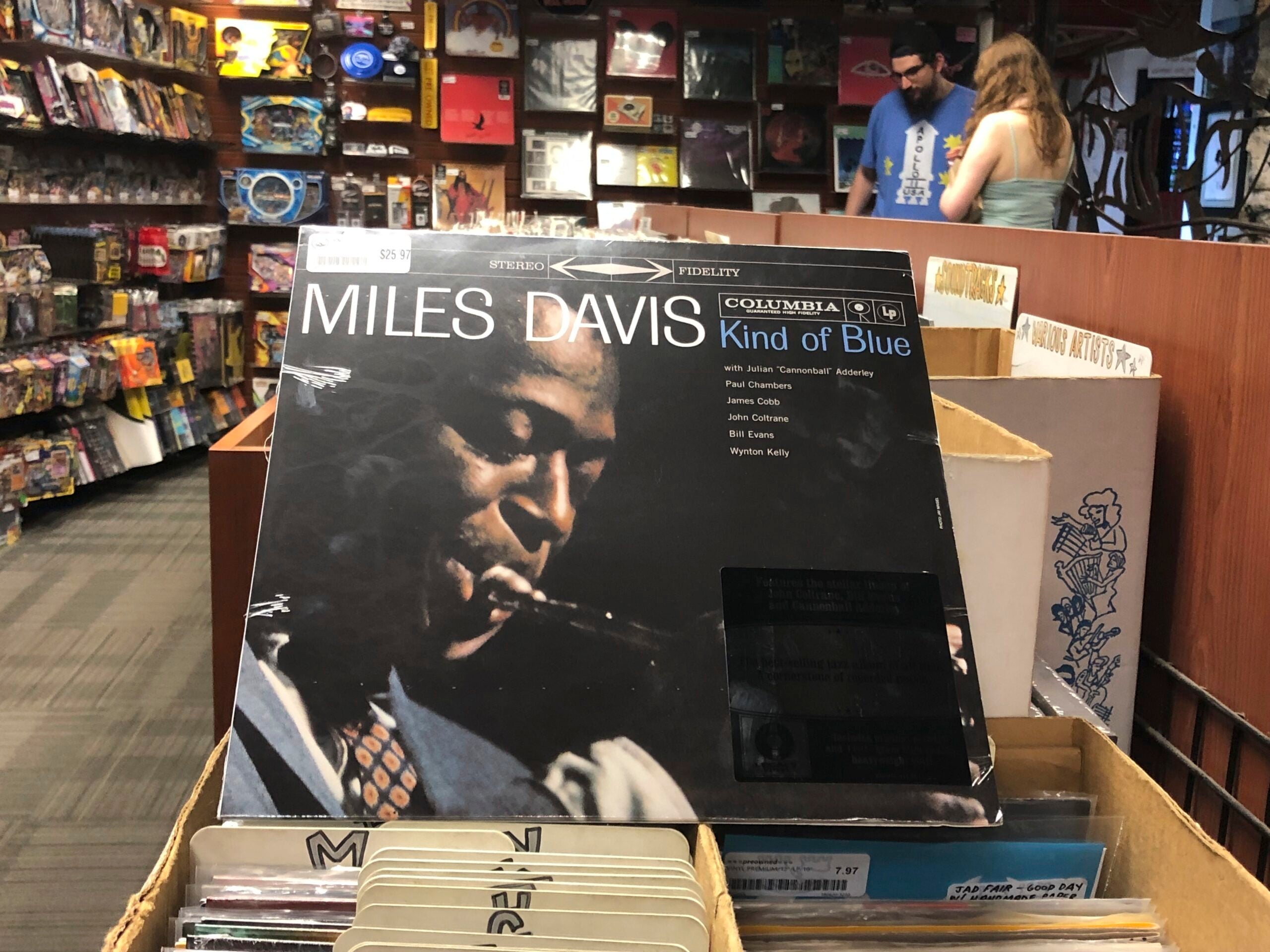

As a result, Coleman was the patron saint for generations of musical oddballs, sonic eccentrics and devotees of the bleeding edge. Key contemporaries like Cecil Taylor, Pharaoh Sanders, Sun Ra and Albert Ayler followed and expanded upon Coleman’s pioneering vision. Meanwhile, the music’s towering figures — Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Charles Mingus and Sonny Rollins — all subsequently embraced aspects of Coleman’s ideas into their music, even if they shied away from overt praise.

Beyond the insular jazz world, Coleman inspired many in the rock world as well, playing with figures ranging from Lou Reed, Captain Beefheart, the Grateful Dead and Sonic Youth, among others. Perhaps taking note of that sway, Coleman began experimenting with electric instruments in the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s with his group, Prime Time. He even branched out to include world-music instruments and musicians into his work.

Coleman continued recording and performing until very recently, but his most crucial work came in that initial burst in the late ’50s and early ’60s. However, his subsequent work continued in that vein and never surrendered in the face of institutional resistance or audience indifference.

Cliché is never a word one would use to describe Coleman’s genius.

Here are five of Coleman’s most renowned compositions:

“Lonely Woman”

“When Will The Blues Leave”

“Free Jazz”

“Kaleidoscope”

“Dancing In Your Head”

Bonus Tracks:

Documentary Performance

Here’s a documentary, purportedly from 1966, that shows Coleman’s trio rehearsing before cameras. Interspersed between the performances are interview snippets and some strange theatrical scenes that are likely part of the presentation.

“Free Jazz”

This clip — the first of three videos on YouTube — captures a live, sprawling performance by Coleman’s late ’70s sextet in Germany. This group featured many of Coleman’s most renowned pupils from the ’70s and ’80s, including guitarist James Blood Ulmer, drummer Ronald Shannon Jackson and Coleman’s own son, Denardo, also playing drums.