Many of you have reached out to us to say how much the music on WPR matters to you during these challenging times posed by the new coronavirus. We’ve been grateful to hear listeners describe how music can be calming, reassuring, and inspiring. Especially when the news, important as it is, can sometimes feel so exhausting.

Since you’ve told us what kinds of music are a help to you, our hosts wanted to share some of the music that does the same for them.

Stephanie Elkins, ‘Morning Classics’ Host

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

For self-soothing during anxious times, one of my favorite solutions is baroque music played on the harp. The sound is comforting and makes me feel safe. It helps me appreciate that there is still loveliness and beauty amid fear and tragedy.

Years ago, I volunteered as a classical host for a community station in Wisconsin, where I discovered a recording by native daughter Victoria Drake. She grew up in Milwaukee and now has a very successful career as a freelance harpist and recording artist in New York City.

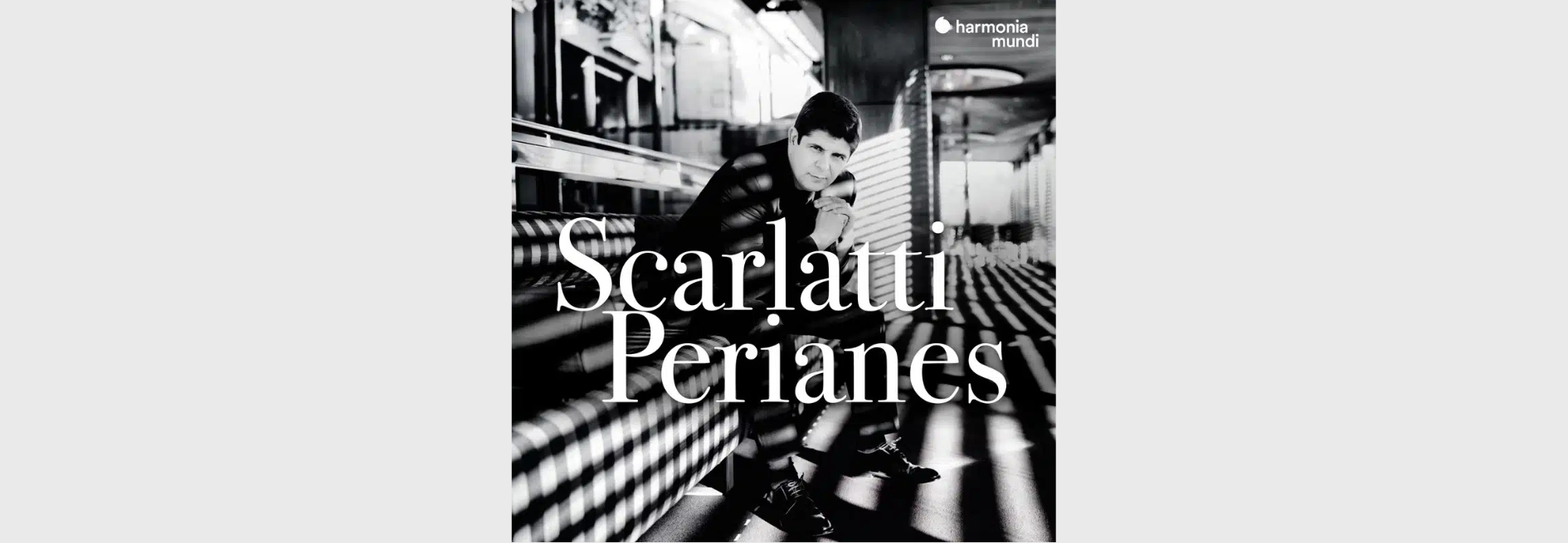

Drake’s recording, “Scarlatti’s Harp,” features her transcriptions of keyboard sonatas by Domenico Scarlatti, and I fell in love with the roundness and resonance of the sound combined with the orderliness and unique beauty of each sonata. It made such an impression that I bought my own copy and found I was playing it whenever I needed comfort or solace.

Drake has gone on to create more wonderful baroque recordings, including the complete “Solo Cello Suites” by Johann Sebastian Bach — another synthesis of beauty, order and (especially on the harp) warm resonance.

It’s music that serves as a balm for my soul; music that works its way into body, mind and spirit and lifts me up; music that’s reassuring during challenging times.

Listen to Drake play, talk about discovering baroque music and discuss her deep connection to Bach’s music here.

Listen to harpist Maria Luisa Rayan-Forero playing Scarlatti, and hear harpist Catrin Finch performing Bach’s “Italian Concerto” below:

Lori Skelton, ‘Afternoon Classics’ Host

When I was in college, I discovered that the Bach solo cello suites were, among other things, the best music by which to study. Something in the structure of those long lines, always moving forward, with harmony that was hinted at, rather than hammered out, helped my brain to focus.

I’ve been fascinated by music for solo strings ever since; the beauty is obvious, but you can really pay attention to the craft of the composer, as well as the soul of the soloist.

Inspired by the Bach solos and partitas for violin, the Belgian commposer/virtuoso Eugène Ysaÿe wrote six short solo sonatas in 1923. Each one was dedicated to a different contemporary virtuoso, and each one is full of the most demanding techniques for a performer.

The composer, however, was adamant that a performer be “a violinist, a thinker, a poet, a human being, he must have known hope, love, passion and despair, he must have run the gamut of the emotions in order to express them all in his playing.”

The final sonata, No. 6 in E Major, was dedicated to the Spanish virtuoso Manuel Quiroga, and has elements of the Habanera, which will have at least part of your brain dancing as you listen.

Dan Robinson, ‘Simply Folk’ Host

A driving song with a great message, a little whimsy, and some terrific instrumental licks, We Banjo 3 has a wonderful musical combination for feeding the soul and cheering the heart.

The quartet of two sets of brothers — Enda and Fergal Scahill and Martin and David Howley — is originally from Galway, Ireland, and they call their style of music “Celtgrass.” You can often find them touring around Wisconsin, as they’re popular performers in the state.

They even stopped by WPR’s Madison studio in 2016 for an interview and performance for “Simply Folk,” and their cut of this song from that session is included in the show’s 40th anniversary collection.

Ruthanne Bessman, ‘Classics By Request’ Host

I asked my daughter who is hunkered down in New York City what music would help take her mind off the breaking news about the new coronavirus — perhaps something calming or reassuring, meaningful or hopeful. She immediately thought of two pieces: the music to “The Lord of the Rings” by Howard Shore and “Buckbeak’s Flight” from “Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban” by John Williams.

In both movies the scores follow their stories while taking us through their quest and battling the danger that lies ahead, full of unknown trials and tribulations, all the while, the heroes make the best of what their journey is.

“The Lord of the Rings” suite includes many of the memorable themes from the movies. In this recording, flutist James Galway draws us in throughout the work. Howard Shore’s nostalgic score follows the fantasy adventurers’ journey — the struggles of the fellowship to their triumphant ending.

John Williams’ soundtrack to “The Prisoner of Azkaban” is thrilling! The orchestration for “Buckbeak’s Flight” begins with wild drum beats while a shocked Harry takes off on the flying hippogriff. The music intensifies as the pair soars into the sky with exciting sounds from the strings and brass. It’s a glorious scene that finally ends with the two landing safely back. Truly an example of the composer’s magic at his best.

Anders Yocom, ‘Sunday Brunch’ Host

I am tempted to suggest light music that is easily accessible and would, under ordinary circumstances, lighten my mood. With something as pervasive and profound as the COVID-19 pandemic, with all of its ramifications and lasting effects on our country and all of the people of the world, I rely on my lifelong musical mainstays: the symphonies of Gustav Mahler and in particular the sixth and final movement of his “Symphony No. 3.”

For this crisis, lighter music like Strauss waltzes, delightful as they are, come across as trite. Mahler digs deep into human emotions ranging from the deepest sense of despair to the highest levels of exultation. That movement supports the dismay many are feeling now, but also ends with a thrilling coda of elation and hope.

Norman Gilliland, ‘Midday’ Host

If you want calming and reassuring, the ultimate is Bach’s “Goldberg Variations,” which, according to an unlikely story, he wrote for young Johann Goldberg to play to lull Count Hermann Karl von Keyserlingto sleep. Glenn Gould made recording history with his top-selling 1955 recording:

Another good choice would be Mendelssohn’s “Octet in E flat,” played here by the Jasper String Quartet plus four. The irrepressible youthfulness of which is inevitably uplifting. Not bad work for a 15-year-old.

Jonathan Overby, ‘The Road to Higher Ground’ Host

The opportunity to share a few thoughts on the therapeutic power of music to heal, nurture and comfort is one I relish. Why? Well, for me, music is more than an alignment with a deeply spiritual feeling. It is a way of life rooted in an evolving relationship that inspires and challenges me to increase my understanding of people and their daily traditions. I suspect that for many of you, music lifts you up similarly.

That said, one cannot ignore the existence of, potential exposure to, or the threat of this global pandemic and how it dispassionately injures to our daily way of living. And yet there is some relief through listening to music — it can give us relief from the ills of the day and provide encouragement and strength.

Today we see universal suffering caused by the same enemy. I hold that music can “fight the good fight” and have a good international effect on the mind and the body by contributing to our collective well-being, especially now.

For me, Paul Simon’s song “Bridge Over Troubled Water” tells how we might navigate these trying times. It is said that Simon first heard the motif by a gospel group singing at a Baptist church. The late gospel and soul singer Aretha Franklin’s interpretation speaks in a language I hope we can all understand, appreciate, and find comfort in.

Peter Bryant, NPR News and Classical Music Network Program Director

The fifth symphony of English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams is a personal favorite. It was premiered in London during World War II, at a time of air raids, shortages, and great uncertainty.

The beauty and serenity of the music was welcomed by many as a relief from their day-to-day challenges. At the same time the music has moments that seem to express the anxieties that most people must have been feeling. The result is something that feels full of hope, but also grounded in reality.

Whether this was what the composer meant is something we’ll never know. He knew that each listener would apply their own meaning to what they heard, which seems right.

The third movement of the symphony is a good example:

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.