In the late 1800s, fires were a fact of life.

The 1871 Peshtigo Fire burned more than 280,000 acres and killed 1,500 people in eastern Wisconsin, while on the same night the Great Chicago Fire burned through the city killing 300 and leaving 100,000 homeless.

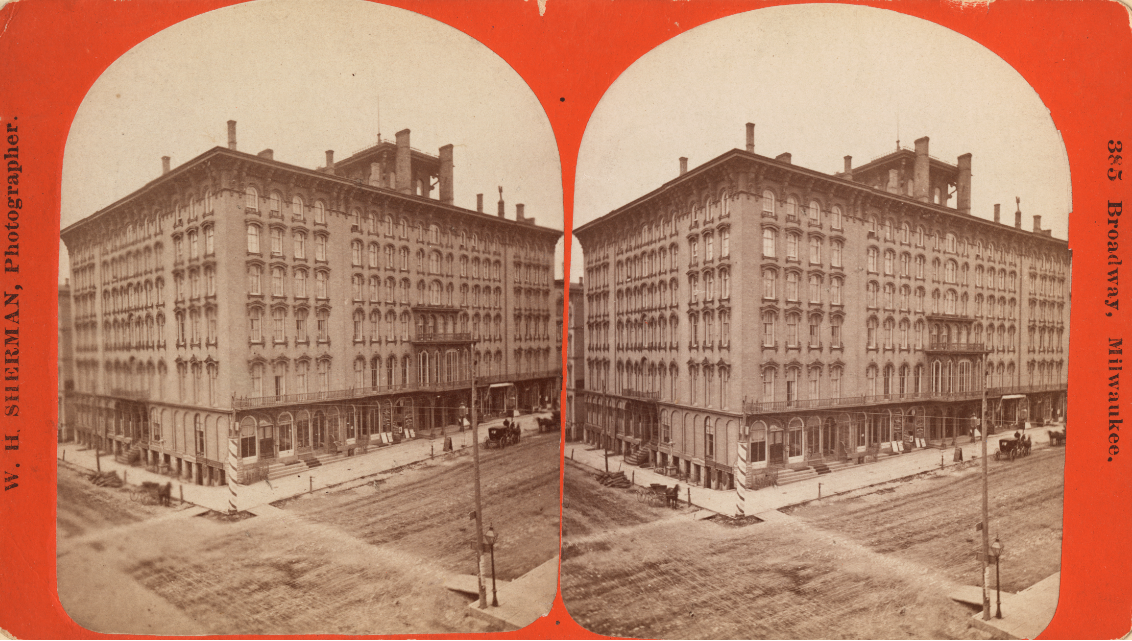

The Newhall House Hotel in 1874. WHI Image ID 7466

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

In the history books, those massive fires have overshadowed another devastating fire in the region that occurred roughly a decade later, one that’s cause remains a mystery to this day.

On a cold night in January 1883, a fire began in the basement of the luxury Newhall House Hotel in Milwaukee that took over 70 lives — making it one of the deadliest, unsolved possible arsons in American history.

The Newhall House Hotel fire, along with its history and tumultuous finances, is the subject of the new book, “Damn the Old Tinderbox!” by Matthew Prigge, a Milwaukee historian and host of WMSE’s “What Made Milwaukee Famous.”

A porter discovered the fire at about 3 a.m. when the elevator he was in began to fill with smoke. By the time they located the flames, the fire was well underway.

“They made the assumption that this was something they’d be able to handle themselves,” Prigge said. “We’re talking just a few minutes here, but by the time they realize that this was beyond their control, the fate of the house was pretty much sealed.”

The main hall of the hotel in 1881. WHI Image ID 54277

Had the fire started at a different hour, the events may have been different, he said. But at that hour, all but three staff members in the hotel were asleep.

“Catching in the elevator shaft like that, it was able to spread very quickly because elevators of those times they had open caps on the roof above the elevator shaft, and especially being such a cold night, the warm air of the hotel was being drawn up through this elevator shaft,” he said.

Firefighting was a different profession in the 1880s, Prigge said, and by the time they arrived on the scene — about 10 minutes after the fire started — the best they could do was try and prevent the fire from spreading through the streets and get ladders to those trapped in their rooms.

The hotel had seen fires before this event, each one handled in-house either with fire hoses or the buckets of water scattered throughout the building in case of fire.

Allegedly, several of those fires had been intentionally set, he said.

“That obviously raises a lot of red flags,” Prigge said. “But in the aftermath of the big fire … people talked about it in sort of hushed tones.”

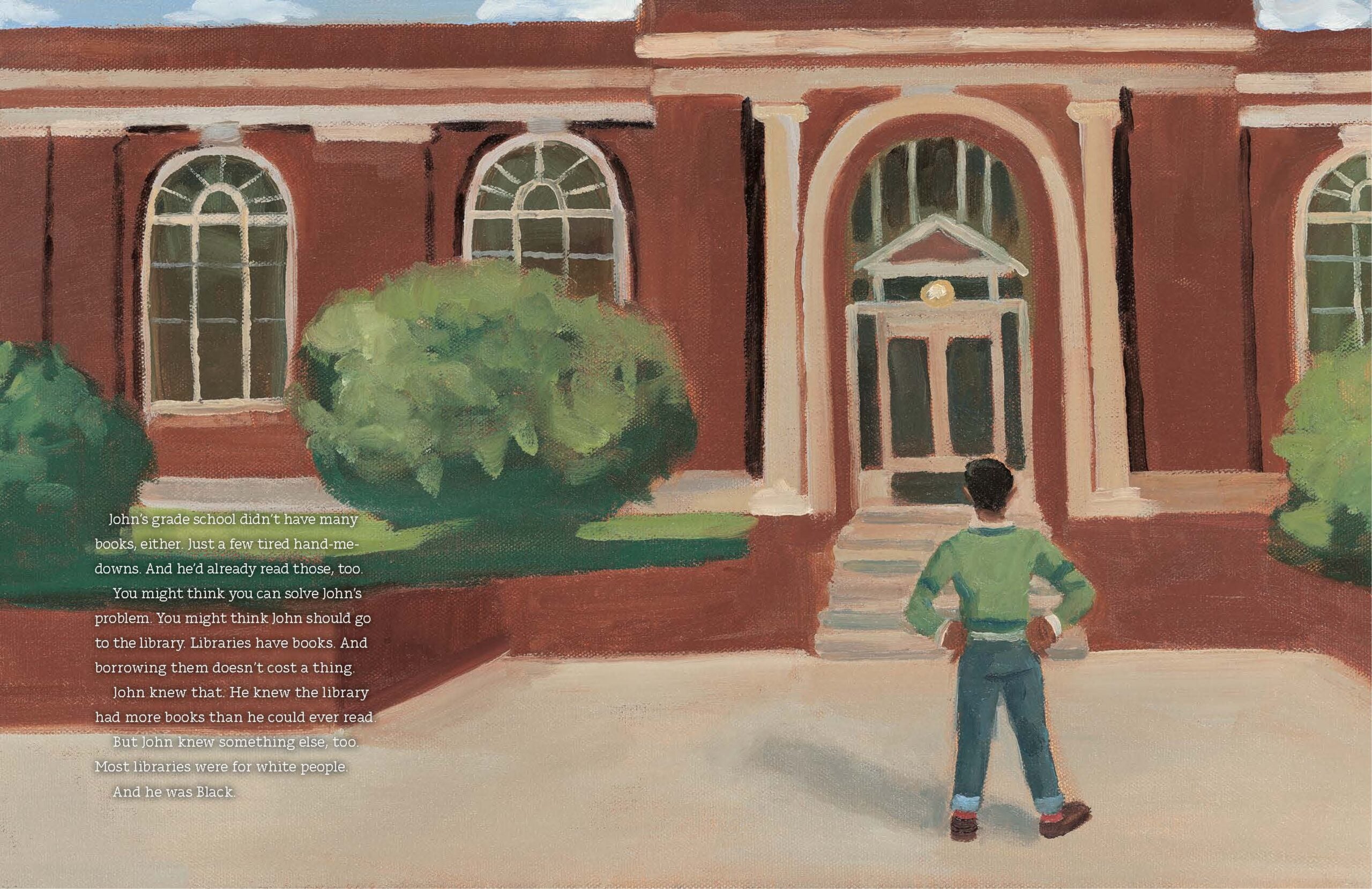

The cover of Harpers Weekly of the Newhall House Hotel Fire in January 1883. Photo from the Milwaukee Fire Department

For a time, suspicion followed the hotel’s bartender, who was charged and put on trial for starting the fire, but was eventually acquitted.

“I don’t think it’s too much of a spoiler to say that by the end of that trial the city was basically celebrating his acquittal because it became so clear that he had nothing to do with this,” Prigge said.

While one might expect the city of Milwaukee adopted stricter fire safety codes after the tragedy, it would be some years before that would happen, he said.

“Not much happened in the aftermath of this fire in terms of requiring more from the people who own these buildings, more clearly marked fire exits, things like that,” Prigge said.

“Damn the Old Tinderbox” will be released on March 19 with a talk and book signing at Boswell Book Company in Milwaukee at 7 p.m.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.