It’s been four years since the 2020 election upended American politics, when former President Donald Trump falsely claimed massive voter fraud led to his defeat, culminating in efforts to overturn the results and, ultimately, a deadly riot at the U.S. Capitol.

Since then, there has been a notable loss of trust in the electoral process among some voters and a surge of legal challenges. But there have been relatively few changes to how Wisconsin actually administers elections.

Now, with Trump again on the ballot, this time in a close race against Vice President Kamala Harris, there’s a real chance Wisconsin could see a repeat of 2020’s election drama.

Here’s what’s changed since then, and what hasn’t.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Drob boxes disappear and reappear

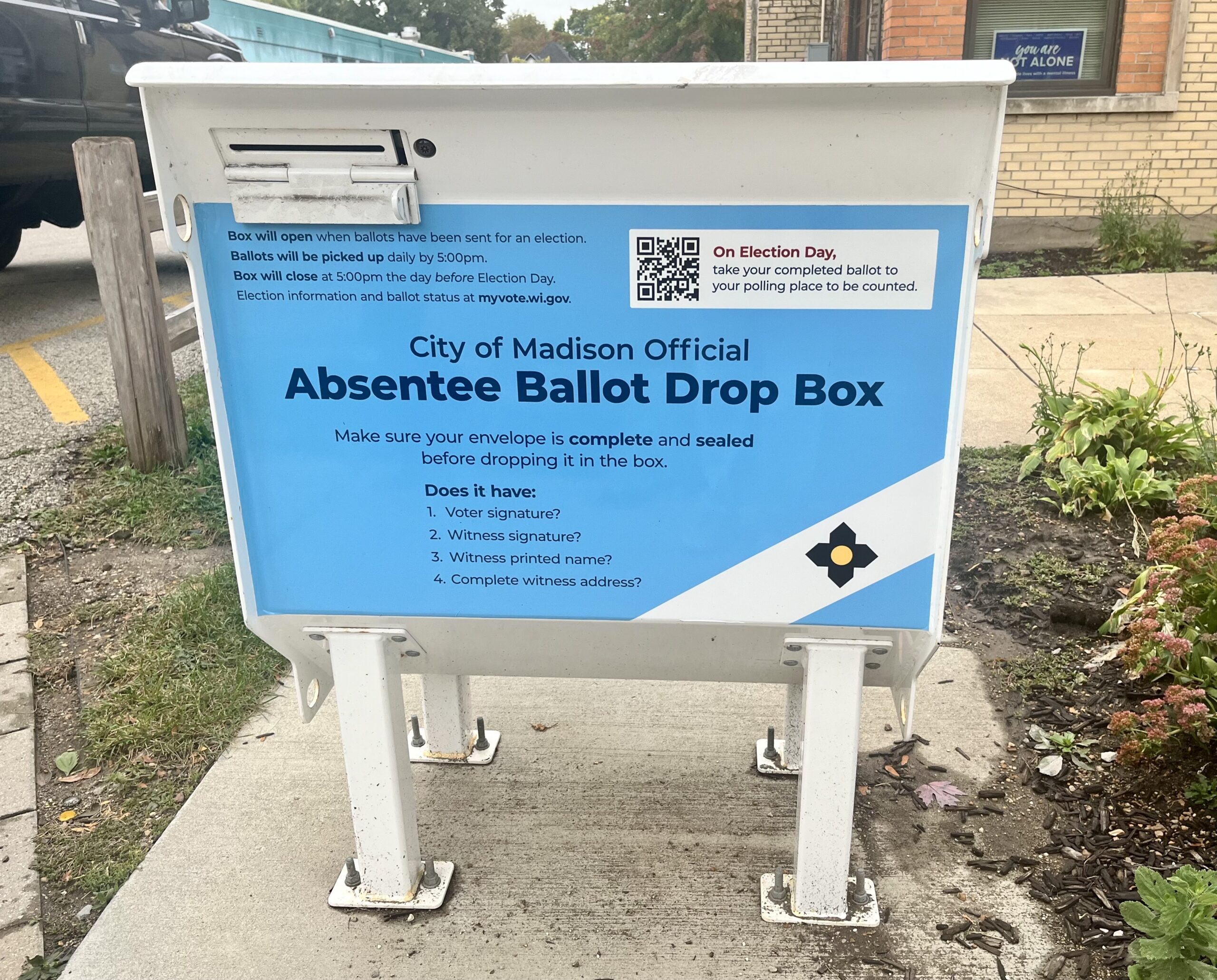

It can be tough to keep up with the onslaught of election lawsuits, but residents of some Wisconsin communities could track the fight over drop boxes simply by watching the receptacles themselves get bolted shut or removed, and then reopened or brought back.

Drop boxes became more common during the COVID-19 pandemic, when absentee voting in Wisconsin surged. According to the Wisconsin Elections Commission, 528 were used in more than 430 communities that year.

In 2022, the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s former conservative majority ruled in favor of a conservative law firm and declared drop boxes illegal. But the state Supreme Court flipped to liberal control in 2023, and this year, the new majority reversed that ruling, bringing drop boxes back.

Despite the court’s shift on drop boxes, far fewer clerks are using them ahead of the November election, and they are still a political flashpoint. In late September, Wausau Mayor Doug Diny physically removed a drop box outside of City Hall. The Wisconsin Department of Justice is investigating whether Diny broke the law.

In Dodge County, municipal clerks opted against using drop boxes after Sheriff Dale Schmidt urged them not to in order to prevent the “perception of election fraud.”

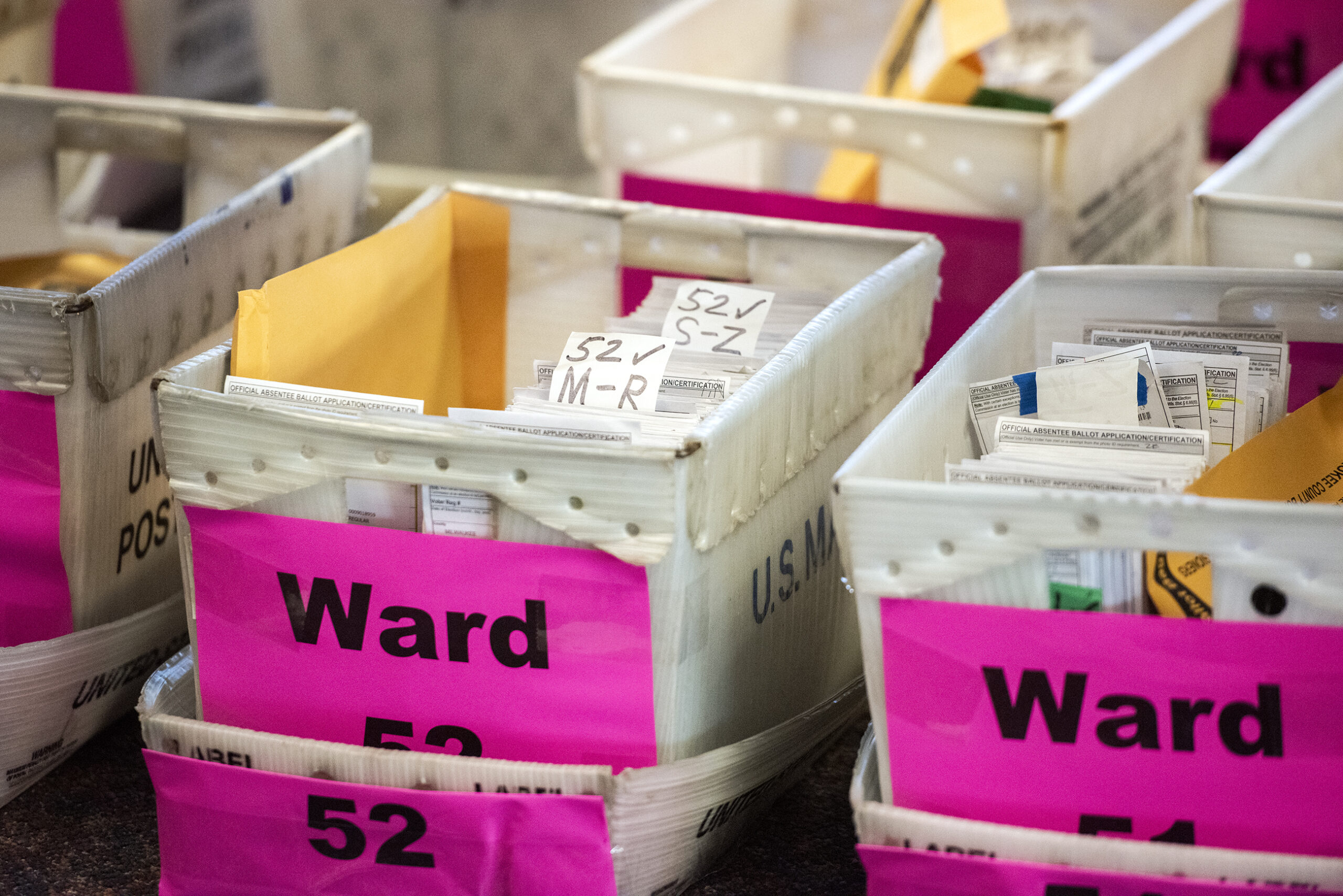

Clerks lose, then regain discretion on absentee ballot witness certificates

The rules for how clerks can handle absentee ballot witness certificates also pinged back and forth, thanks again to the court system.

The rules in place for the 2020 election were unanimously approved in 2016 by the bipartisan Wisconsin Elections Commission.

That guidance, which was aimed at reducing the risk of accidental voter disenfranchisement, told clerks they could fill in missing address information like a zip code on a witness certificate. It was never challenged until Trump tried to reverse his 2020 loss.

In 2022, a Waukesha County Circuit Court judge ruled clerks cannot correct missing info and ordered the WEC to rescind its guidance. That meant absentee ballots with incomplete addresses had to be rejected.

In January, a Dane County Circuit Court judge issued two rulings stating that rejecting ballots due to incomplete witness address information violates the federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 and that the definition of an address should mean “a place where the witness can be communicated with.”

In July, a Wisconsin Court of Appeals largely sided with the Dane County rulings, which means that for the 2024 election, clerks will retain the power to count ballots sent with impartial witness certificates, if a clerk can determine where the witness can be reached.

A new batch of lawsuits filed on the eve of the 2024 election

The most recent lawsuits in Wisconsin come on the eve of the 2024 election, as hundreds of thousands of absentee ballots have already been returned. They claim large numbers of people who are not eligible to vote are labeled as active on Wisconsin’s voter registration list, and they’re asking the courts to make big, last-minute changes.

One of the cases, filed by a lawyer involved with efforts to overturn Wisconsin’s 2020 election results, claims more than 56,000 Milwaukee residents listed as active are invalid based on cross references with U.S. Postal Service data. A Milwaukee County judge dismissed that case earlier this week.

The other suit, filed by another lawyer involved in a lawsuit seeking to overturn Trump’s 2020 loss, alleges there could be around 10,000 noncitizens registered to vote in Wisconsin. It’s asking a Waukesha County judge to order the WEC and Wisconsin Department of Transportation to cross-reference data for millions of residents on the voter rolls before Nov. 5.

Attorney Bryna Godar of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Democracy Research Initiative told WPR the lawsuits are an example of how litigation is focusing more on “those granular issues of election administration.” She said the timing of the suits raises questions about whether attorneys are hoping to preserve legal claims that can be used to challenge Wisconsin’s results depending on who wins.

“But then I think the other purpose that these might be serving is simply fueling messaging about voter fraud or noncitizen voting, and really feeding into this narrative that elections can’t be trusted anymore,” Godar said.

UW Law Professor Robert Yablon, the co-director of the Democracy Research Initiative, said the volume of election-related litigation Wisconsin has seen this year is already higher than in all of 2020.

Any appeals of state election lawsuits could ultimately be decided by the Wisconsin Supreme Court, where liberals now have a 4-3 majority. At the federal level, conservatives hold a 6-3 majority on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Early in-person voting is higher than in 2020

The COVID-19 panic dramatically changed how Wisconsinites voted in 2020. All told, nearly 2 million residents cast absentee ballots.

Trump discouraged absentee voting in 2020. But after years of sowing doubt, Republicans have called on supporters to embrace it this election cycle. Traditionally, Democratic leaders have pushed early voting more than their GOP counterparts.

Because Wisconsin doesn’t require voters to register by party, it’s impossible to know whether Trump’s call has boosted GOP absentee voting and contributed to a surge of in-person absentee voting this year. But what’s clear is more voters are casting ballots that way than in 2020.

This year, 801,083 people had cast in-person early ballots as of the final Friday before the election, according to the WEC. That’s about 48 percent higher compared to the same Friday in the 2020 election cycle.

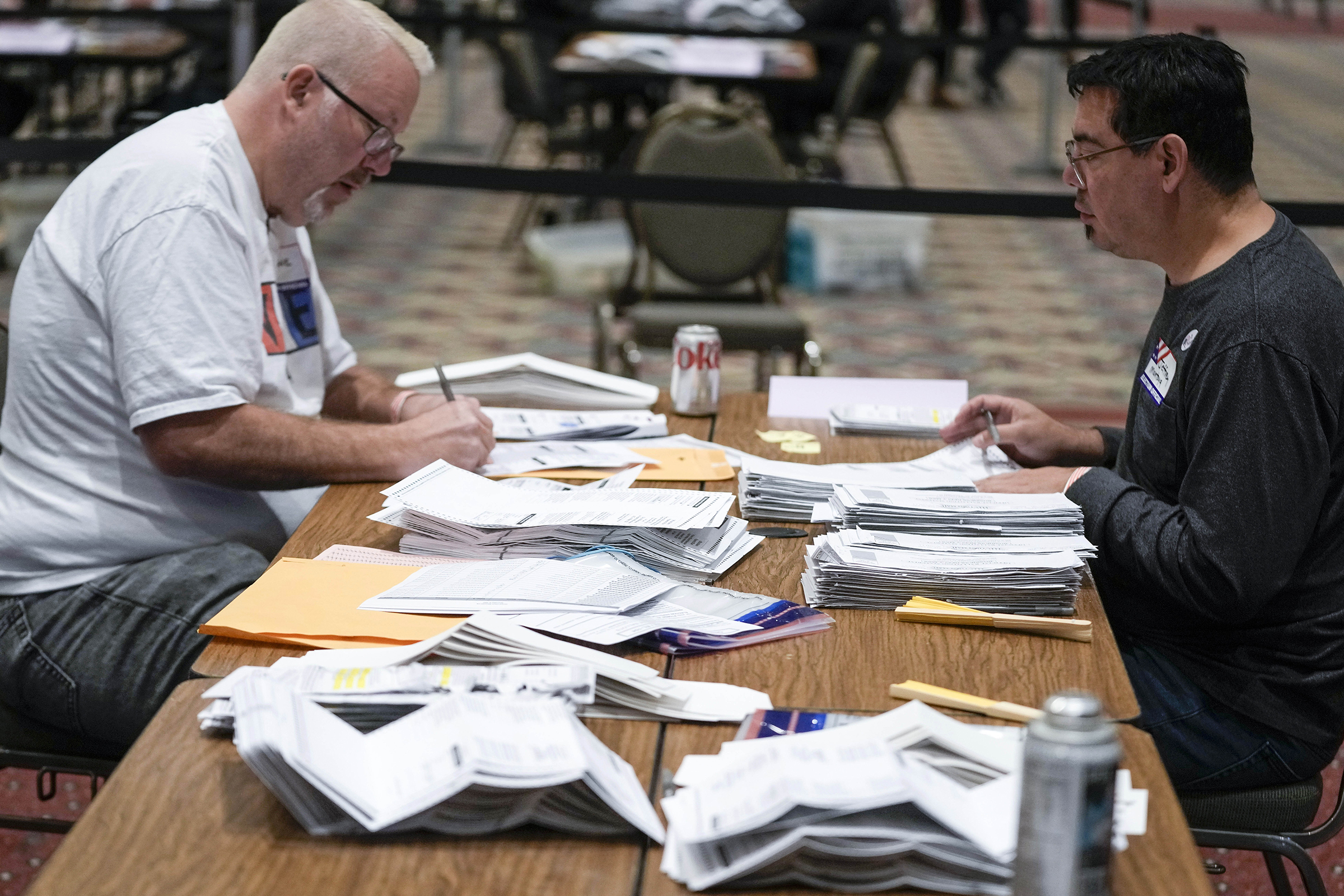

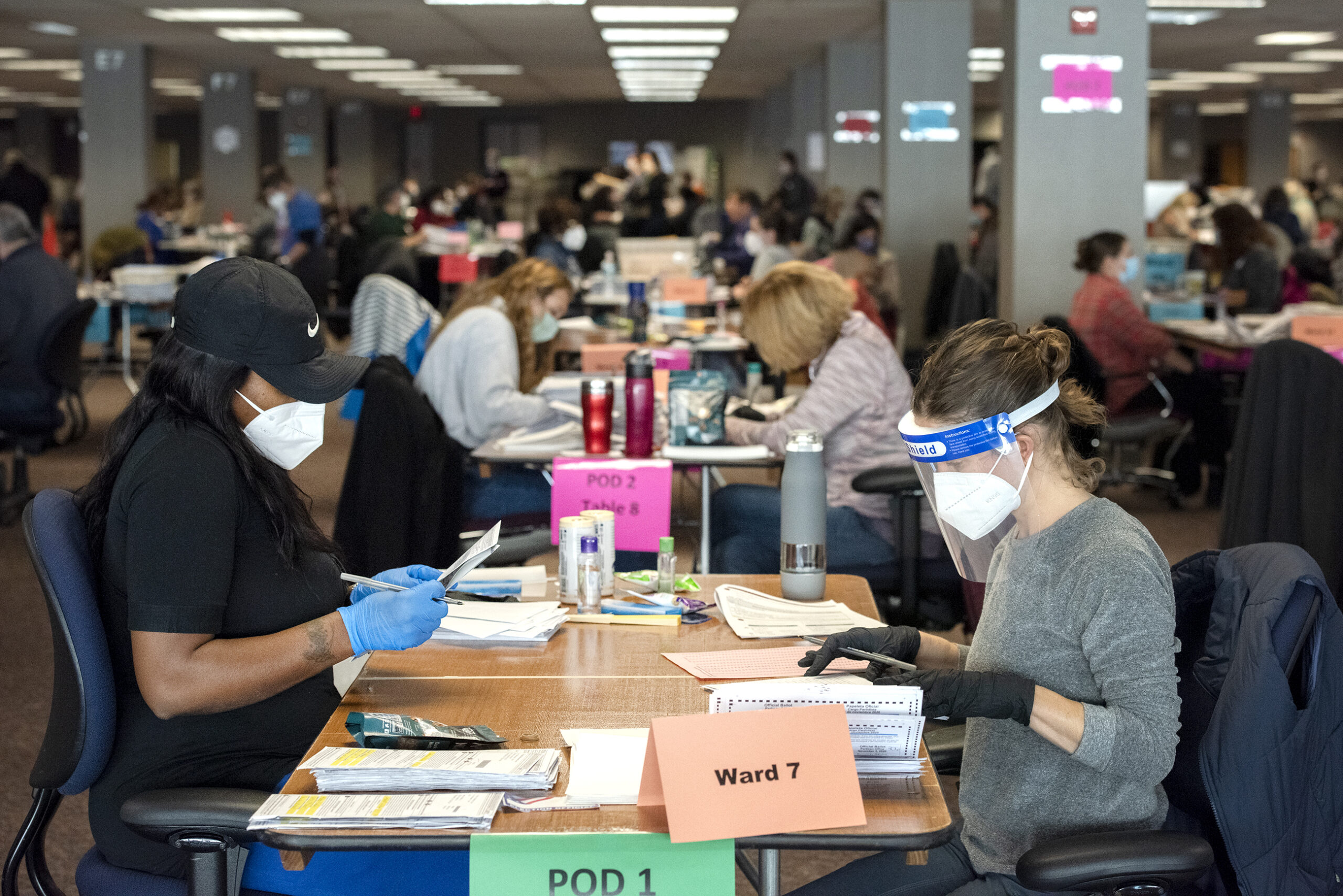

Efforts to speed up the count on Election Day went nowhere

The surge of early in-person absentee voting, coupled with hundreds of thousands of ballots sent to clerks by mail, means it could be another late night for election officials in large cities like Milwaukee. In 2020, Trump held an early lead in the Associated Press’ unofficial results on election night until Milwaukee’s totals were reported. That led to false claims from Trump of “ballot dumping” in the Democratic stronghold.

In hopes of avoiding similar situations in the future, a bipartisan group of lawmakers in the Wisconsin Legislature introduced a bill to let some aspects of absentee ballot processing begin the day before the election. The bill died, however, after Republicans who run the state Senate never brought it up for a vote.

Kathy Bernier, a former Republican state senator from Chippewa Falls and a longtime clerk, said the legislation became known as the “early count bill.” She said that led to fears among some GOP lawmakers that information on vote totals counted before the election could be “leaked” by clerks.

“There were a number of Republicans, to my understanding, that were not terribly comfortable with that process,” Bernier said. “Because they didn’t fully understand how that was going to work.”

Bernier said that wouldn’t have been possible because information in voting machines wouldn’t be known by anyone until a report was run after polls close on Election Day.

GOP, voters ban private election grants

There were other areas of election administration that did change.

Amid the stolen election claims, Trump and Wisconsin Republicans trained their focus on private grants in the 2020 election from a group called the Center for Tech and Civic Life, an organization funded by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg.

The grants, which a federal judge ruled were legal before the 2020 election, distributed millions of dollars to communities throughout the state, both large and small. But the bulk of the funding went to Wisconsin’s largest cities, leading to claims by Republicans that the money was used to promote turnout in places with more Democratic voters.

Republican state lawmakers passed a resolution to ban the grants, which was ultimately approved by voters in April. That means private grants won’t factor into the 2024 election.

False electors admit wrongdoing, Congress passes law to prevent a repeat

One tactic Trump’s campaign used in 2020 — leaning on Congress to challenge state election results — would be harder to pull off in 2024.

The idea was hatched four years ago by two of Trump’s lawyers — Kenneth Chesebro and Jim Troupis — who were working on a lawsuit challenging Wisconsin’s results. It involved sending an “alternate” slate of electors to Washington, and having Congress count these electors instead of the real ones.

On Dec. 14, 2020, the same day the Wisconsin Supreme Court ruled against Trump’s lawsuit seeking to overturn the election, and the same day Wisconsin’s actual presidential electors met, 10 Republicans posing as electors gathered in a state Capitol conference room and signed official-looking documents declaring Trump the winner.

Republicans sent these documents to U.S. Sen. Ron Johnson’s office, where Johnson’s chief of staff tried unsuccessfully to deliver them to Vice President Mike Pence. Pence refused to go along with the scheme on Jan. 6, 2020, the day when an angry mob stormed the U.S. Capitol during a deadly riot that briefly delayed the joint session of Congress.

In a legal settlement, Chesebro and Troupis admitted this year that their actions were “part of an attempt to improperly overturn the 2020 presidential election results.” In a separate settlement reached late last year, the 10 false electors reached a similar agreement, and vowed never to serve as electors for Trump again.

Troupis and Chesebro are now facing felony charges in Wisconsin for their role in the false elector plan.

In the aftermath of the Jan. 6 riot, Congress made changes to the federal Electoral Count Act. It clarified the vice president’s role during the certification of electoral ballots as “solely ministerial” and raised the bar for the number of lawmakers needed to challenge a state’s electors from one in each house to 20 percent of the members in each chamber.

Election distrust: aberration or new normal?

Tangible changes aside, it appears the steady drumbeat from Trump and his allies has had an impact on the way many citizens view elections.

A Gallup poll of Americans released in September showed that only 28 percent of Republicans surveyed reported being very or somewhat confident that votes in the upcoming presidential election will be accurately cast and counted.

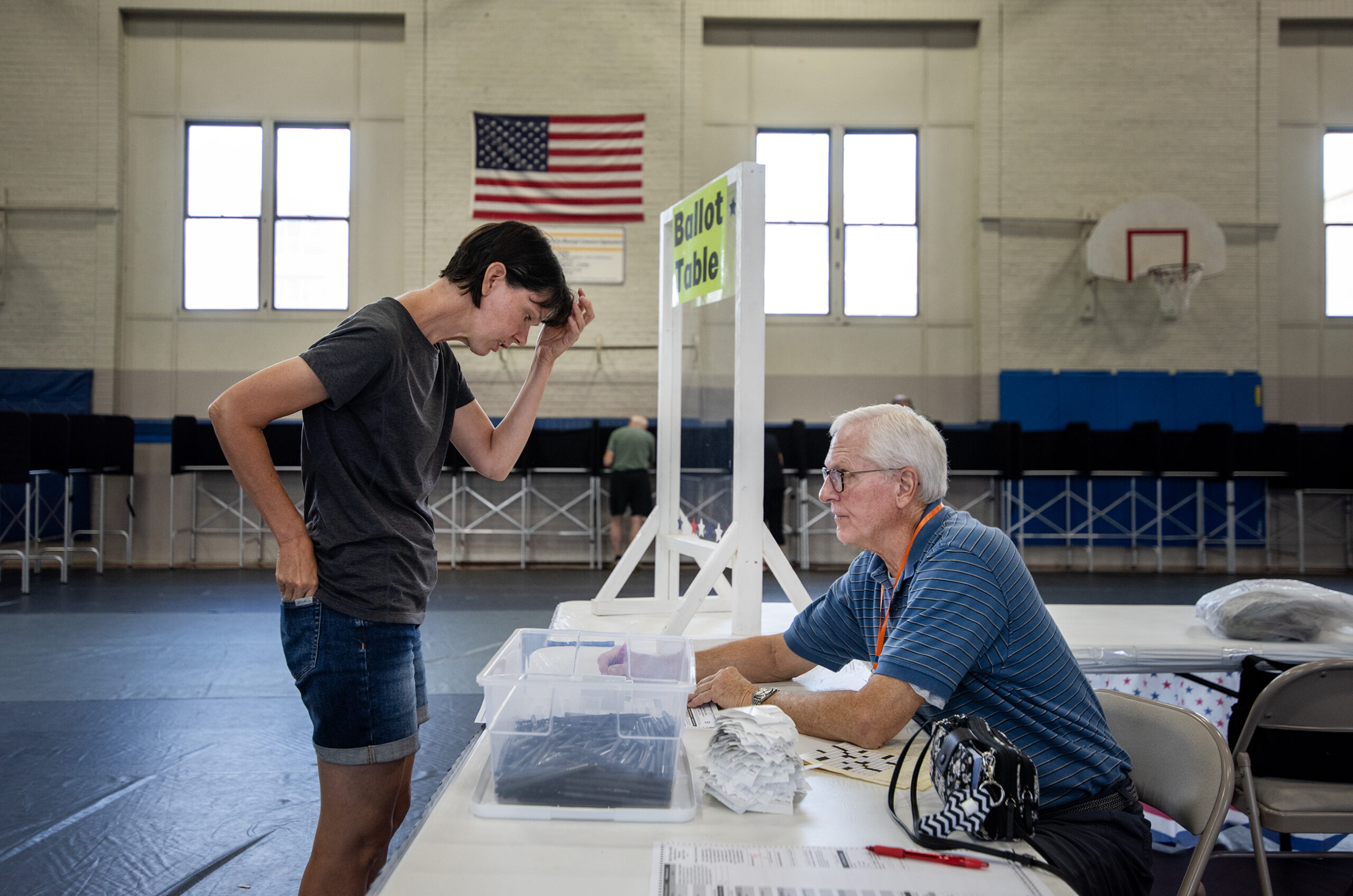

At the local level in Wisconsin, Sun Prairie Clerk Elena Hilby, who heads the Wisconsin Municipal Clerks Association, told WPR that while the conspiracies and misinformation are easy to disprove, there are still people in her own community who no longer assume she and her staff are following the law.

“Now, we’re doing in-person, absentee voting,” Hilby said. “And so, as (voters) they’re leaving, they’re like, ‘Now you’re not going to throw this away, right?’ Or, ‘Now this is going to count, right?’”

Hilby said they try to take it tongue-in-cheek.

“But it’s hurtful because we would never make a vote disappear,” she said. “And if we did, it will be found.”

At this point, Hilby said, her name, phone number and home address is registered with her local 911 dispatch center. She said that’s because some clerks around the nation have been “swatted,” where a fake 911 call leads to an armed police raid on a victims’ house.

Hilby said Wisconsin clerks have also received de-escalation training for potential election related problems. She’s also part of a Dane County-funded program that pays a third-party to remove phone numbers and home addresses for her and her deputy clerks from the internet “because clerks are being harassed in just their normal lives.”

At the state level, increased security measures have been approved for Wisconsin Elections Commission Administrator Meagan Wolfe. A bipartisan bill that would have made it a felony to attack election workers was introduced last year, but failed to pass by the end of the legislative session.

Trump’s repeated false claim that the election was stolen has tested the people and processes behind the sacred right of citizens to choose their elected leaders. But Hilby said she’s optimistic that people’s faith in elections will be restored.

“I’m hoping, if we get through another election and whatever the outcome is, we will show them again that none of the numbers will change, it was all legitimate,” Hilby said. “Maybe after two full presidential cycles, people will be like, ‘OK, alright, there’s nothing going on here.’”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.