Sometimes you just want to remind yourself that there’s still plenty of beauty in our endangered world. These three coffee table books featuring horticultural marvels fit the bill.

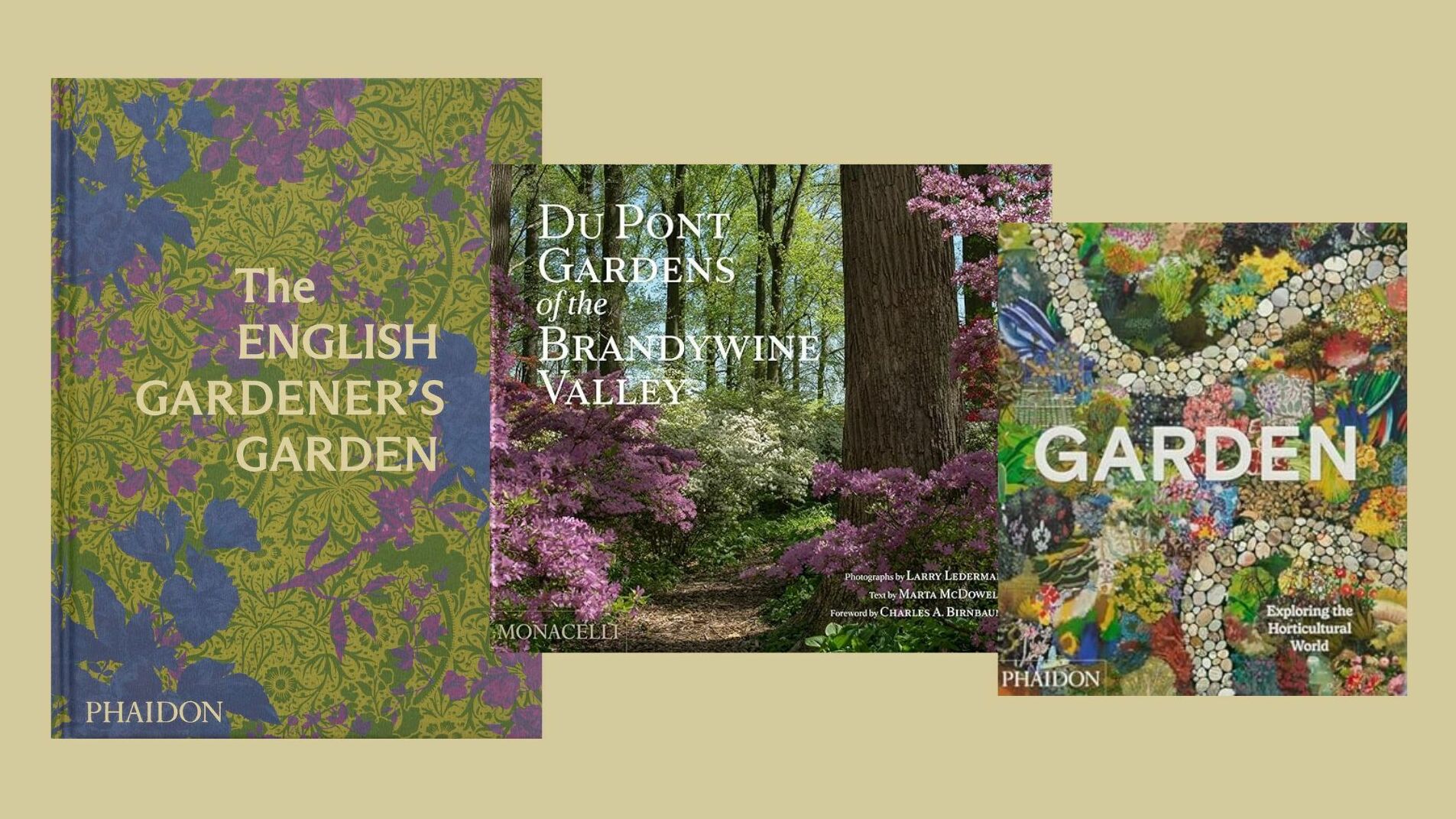

Topping my list is Garden, a wide-ranging survey that spans millennia, continents, and multiple art forms — and could keep you happily engaged for hours. The English Gardener’s Garden narrows the focus to a single country, but again spans centuries and multiple styles in a tribute to Britain’s national passion for cultivating ornamental plants. Rounding out the trio is Du Pont Gardens of the Brandywine Valley, an inviting history and photographic celebration of the seasonal splendors of five Du Pont Gardens open to the public, including Longwood and Winterthur.

All three of these books would make wonderful gifts for gardeners and armchair oglers alike, and may tempt you to book a garden tour — or even plant some bulbs and seeds yourself.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Garden: Exploring the Horticultural World

Phaidon is celebrating its 100th anniversary of publishing art books by taking a well-earned victory lap. Garden follows their splendid Bird, my favorite coffee table book of 2021. It’s another superbly curated, broad-reaching collection, this time ripe with images of garden-related paintings, photographs, advertising posters, jewelry, ceramics, textiles, sculptures, postage stamps, design plans, and seed packages.

Garden chronicles humankind’s enduring love of gardening as it has evolved over four millennia, first from the necessity to cultivate food, but later in a drive to create beauty and paradise on Earth. A more recent focus has been on “Earth friendly” gardens that benefit wildlife and mitigate climate change by creating essential nature reserves and sanctuaries managed and shaped by gardeners.

The more than 300 illustrations in Garden are arranged not chronologically but in idiosyncratic pairs to highlight not always readily apparent comparisons and contrasts. Fortunately, there’s a handy timeline and index at the back of the book.

One can only imagine the tough editorial decisions it took to determine which of thousands of images would make the cut. Among the chosen: A 1913 seed packet hints at some of the varieties fashionable in early 20th century Wisconsin, including pansies, hollyhocks, and foxgloves. Annie Faivre’s lavishly detailed silk scarf for Hermès, in which she captures the palaces and gardens in Sintra, Portugal with a sumptuous palate of blues, greens, golds, and lavender.

Not surprisingly, the Garden of Eden is a recurring motif, represented by Albrecht Dürer’s 1504 engraving of Adam and Eve and C.F.A. Voysey’s Arts and Crafts 1923 wallpaper, among others. Monet, Renoir, Peter Rabbit, Alice in Wonderland, and Olmsted’s plan for New York’s Central Park also make the cut.

Speaking of cut, if you like fancifully clipped bushes, you’ll appreciate Tony Ray-Jones’ 1970 photograph of 16 tightly spaced topiary dogs, 2 cats, and 1 rat in the eccentric Wolverhampton Garden. On the facing page, a film publicity still for Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands features an enormous hand made from steel armatures covered by chicken wire and layers of silk and plastic greenery.

Japanese gardens, including Ryuanji, convey the appeal of gardens as sanctuaries. Toshi Yoshida’s 1963 woodblock print of Ginkakuji Garden, the Zen Buddhist Temple of the Silver Pavilion near Kyoto, with its striking grey raked sand against a backdrop of stylized green pines, is particularly appealing.

More sobering is Dorothea Lange’s 1942 photograph of a Japanese American woman interned during WWII working in the tiny vegetable garden she has planted in front of her barrack home in San Bruno, California.

One of my favorite pieces is Faith Ringgold’s 1991 acrylic painting, The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles. Eight influential Black American women — including Sojourner Truth, Ida B. Wells, Harriet Tubman, and Rosa Parks — are shown seated amidst a field of vibrant sunflowers in Arles, France, working together on a sunflower quilt. Standing just behind the women, somewhat awkwardly — and almost lost among the blooms — is none other than Vincent Van Gogh, at the ready with a vase of sunflowers.

The English Gardener’s Garden

Attention, Anglophiles! The English Gardener’s Garden isn’t a travel guide, but it might help you plot (ahem) your next excursion across the pond. Naturally, it includes national treasures like Sissinghurst, Blenheim, Highgrove, Hampton Court, and the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, with its famous Palm House conservatory.

Many of the featured gardens were built for the estates of the wealthy. There are several examples of 18th century landscape architect Lancelot “Capability” Brown’s work, including Blenheim, Chatsworth, and Stowe, in which naturalistic-looking rolling lawns sprinkled with groups of trees and serpentine lakes replaced more formal patterns.

The book also showcases the work of horticulturist and garden designer Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932), who, with Arts and Crafts architect Edwin Lutyens, designed several iconic English gardens, including that of her own home, Munstead Wood.

The 16th century topiary bushes in Levens Hall are cut in geometric shapes, some of which resemble ladies’ hats. The even more fanciful topiary at Balmoral Cottage, mainly yews clipped into creatures and spirals, is the work of the distinctive 20th-21st century garden designer, Charlotte Molesworth. The Barbara Hepworth Sculpture Garden in Cornwall, also dating from the last century, is an outdoor gallery for her organically shaped stone and bronze sculptures. Decidedly more urban in feel is the Barbican Conservatory and Gardens, in which grasses and terraced plantings soften the art center’s massive, concrete Brutalist architecture.

Highgrove, the longtime home of King Charles III before he ascended to the throne, is surrounded by a mostly informal garden in keeping with his organic principles. There’s a wildflower meadow, a formal axis path from the Georgian house planted with thyme, which is attractive to bees, and yews cut into massive ornamental shapes, looking like oversized imperial crowns.

A useful glossary at the end of the book defines, among other terms, “borrowed landscape” — a feature intrinsic to so many English gardens. It’s about artfully framing the viewshed — often rolling — when planning a garden.

Du Pont Gardens of the Brandywine Valley

Although it’s been said that garden patrons are generally motivated by three things — piety, prestige, and pleasure — this history of the duPonts’ gardens makes it clear that their interests extended from ornamental horticulture to preservation of the trees, stewardship of the land, and public accessibility. Larry Lederman captures their year-round allure in luxuriant photographs.

A few things I learned from Du Pont Gardens of the Brandywine Valley:

- Fourteen du Ponts arrived in America from France in 1800. Led by E.I. (ÉIeuthère Irénée) du Pont — who founded the DuPont Company — they settled in the rolling Brandywine landscape between Philadelphia, Penn., and Wilmington, Del. E.I. was an enthusiastic arboriculturalist, which explains the carefully managed woodlands on his property, Eleutherian Mills, part of the Hagley Museum and Library.

- Longwood, the most theatrical of the five du Pont gardens open to the public, has more than 900,000 tulips on display each spring. (By comparison, the Keukenhof Gardens in Amsterdam plants more than 7 million bulbs each year for their annual tulip festival, featuring some 800 species.) When Pierre S. du Pont bought the 202 acres of Longwood in 1906, at age 36, it was partly out of concern for its extraordinary trees, which were destined for the lumber mill. Longwood’s seasonal exhibitions of orchids, hydrangea and more in the Main Conservatory are spectacular, as are its multi-colored fountain displays in its Open Air theatre.

- Winterthur is a collector’s garden, showcasing specimen trees and plants, including tulip poplars, blue Atlas cedars, heritage Sargent cherry trees, rhododendron, azaleas, and rare peonies. Its founder, Henry Francis du Pont, was also determined to preserve his beloved trees, which are underplanted with a lovely assortment of daffodils, azalea, and other spring blossoms.

- Nemours, with its Beaux-Arts mansion, long tree-lined allées, and formal entry court, is the most European of the gardens, very much influenced by the grand 17th century French style of André Le Nôtre.

And two bonus garden books worth noting:

Fifty Beautiful Gardens, an intricately detailed coloring book for grownups.

Tulips : A Little Book of Flowers, by Tara Austen Weaver, the third appealing, small-format volume, following Dahlias and Peonies, from the Little Book of Natural Wonders series.

9(MDAyMjQ1NTA4MDEyMjU5MTk3OTdlZmMzMQ004))

© Copyright 2025 by NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.9(MDAyMjQ1NTA4MDEyMjU5MTk3OTdlZmMzMQ004))