Inside a nondescript building near downtown Eau Claire, seven residents sat around a large table at nonprofit resettlement agency World Relief’s newest office. They came to the March meeting to learn how they might be able to help refugees who have fled their countries due to war or persecution adjust to life in the region.

“These people have fled their homes and suffered unimaginable loss,” World Relief staffer Jodi Jewell told her fellow residents. “They’ve had to leave behind careers, cultural norms, homes, family members. However, their past difficulties are not what define them. They are some of the most resilient, driven and joy-filled people that you’ll ever meet.”

Globally, the numbers are staggering. In 2022, more than 108 million people around the world were forcibly displaced according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Just 10 years earlier, it was less than half of that.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Around 16,700 refugees have resettled in Wisconsin since 2001. They’ve come from countries like Laos, Iraq, Somalia, Burma, Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Ukraine, according to data from the Wisconsin Department of Children and Families.

The Eau Claire resettlement plan aims to bring 75 refugees to the Eau Claire area by September. So far, 24 individuals from the Democratic Republic of the Congo have arrived.

But in some cases, resettlement plans in Wisconsin have faced a backlash from local citizens and Republican lawmakers.

In 2017, a plan to bring in 26 Syrian refugees to St. Croix County in far western Wisconsin was met with strong opposition and led to Republican former Gov. Scott Walker asking former President Donald Trump for the authority to set limits on refugees and where they come from.

In Eau Claire, critics of the refugee resettlement claimed a city manager made an agreement with World Relief in secret months before the public knew. This spurred Republican lawmakers to introduce state and federal legislation, with one bill aimed at requiring more buy-in from local officials and the other giving the state and local governments the ability to reject new refugees.

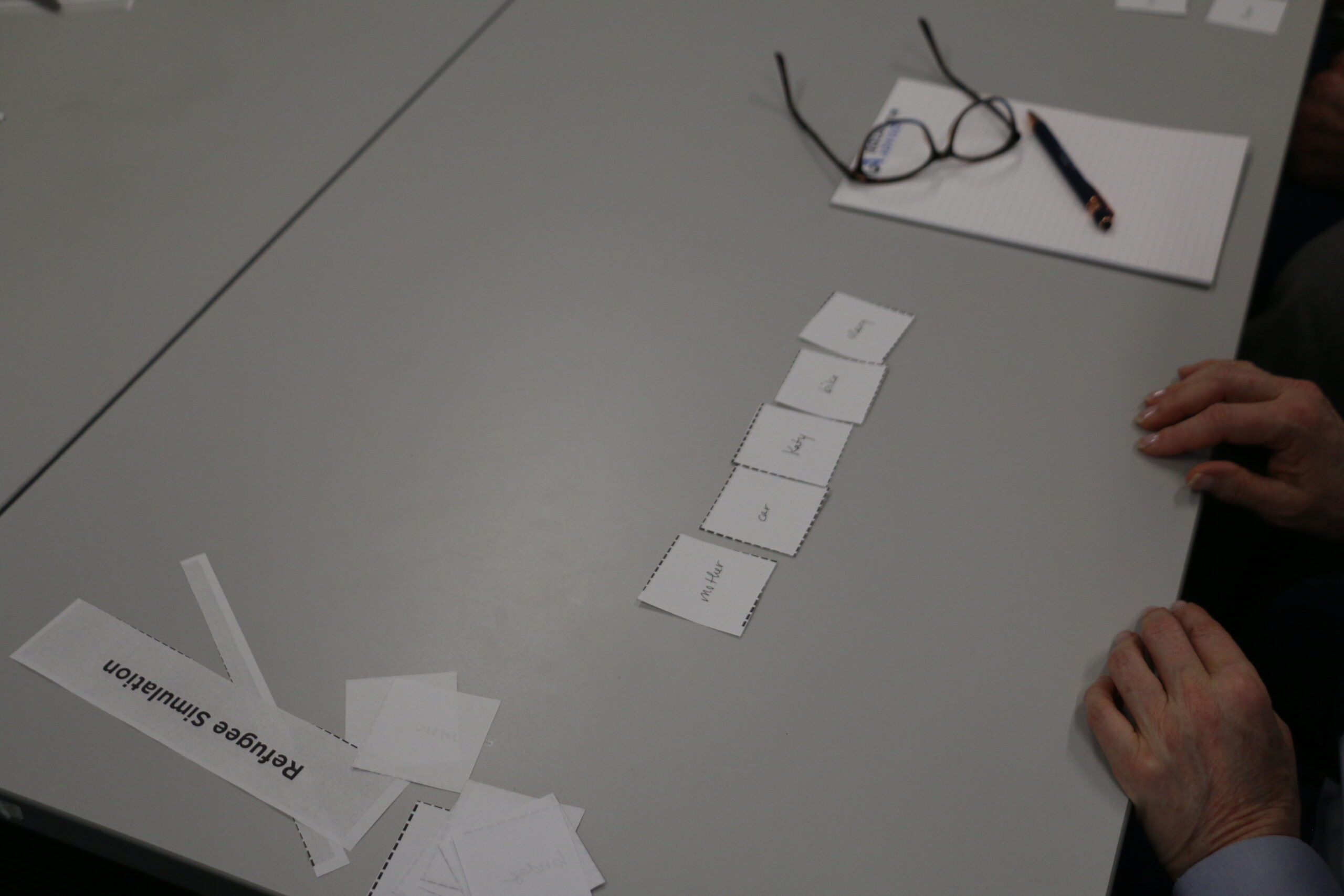

At the volunteer training, Jewell has the group write down the most important people and things in their lives on small white cards. After sharing first-person accounts of the tragedy and loss suffered by refugees, the volunteers have to make a choice.

“You will have 10 seconds to choose one paper from your people category to lose,” Jewell said in a somber tone. “When you have decided, remove that selected paper into a discard pile.”

When asked how they felt about picking a person to leave behind, one volunteer said it felt “like I betrayed them.”

‘We all deserve respect’

Isaak Mohamed is a refugee from Somalia, who moved to the small city of Barron about an hour north of Eau Claire in 2013 as he fled an ongoing civil war. Before coming to Wisconsin, he spent three years living in a refugee camp in Uganda, before moving to the nation’s capitol to earn a bachelor’s degree in social work while serving as a translator for a non-governmental organization called InterAid Uganda.

Two years ago, Mohamed became the first Somali-born resident elected to the Barron City Council. He also works as a Barron Area School District liaison to the local Somali community.

“These people have lived in an asylum country,” Mohamed said of typical refugees. “That means a home that’s not their homeland. They have been a refugee more than 10 years, sometimes some of them 15 or 20 years. Some of the children were born there, generations and generations who lived and grew up in refugee camps.”

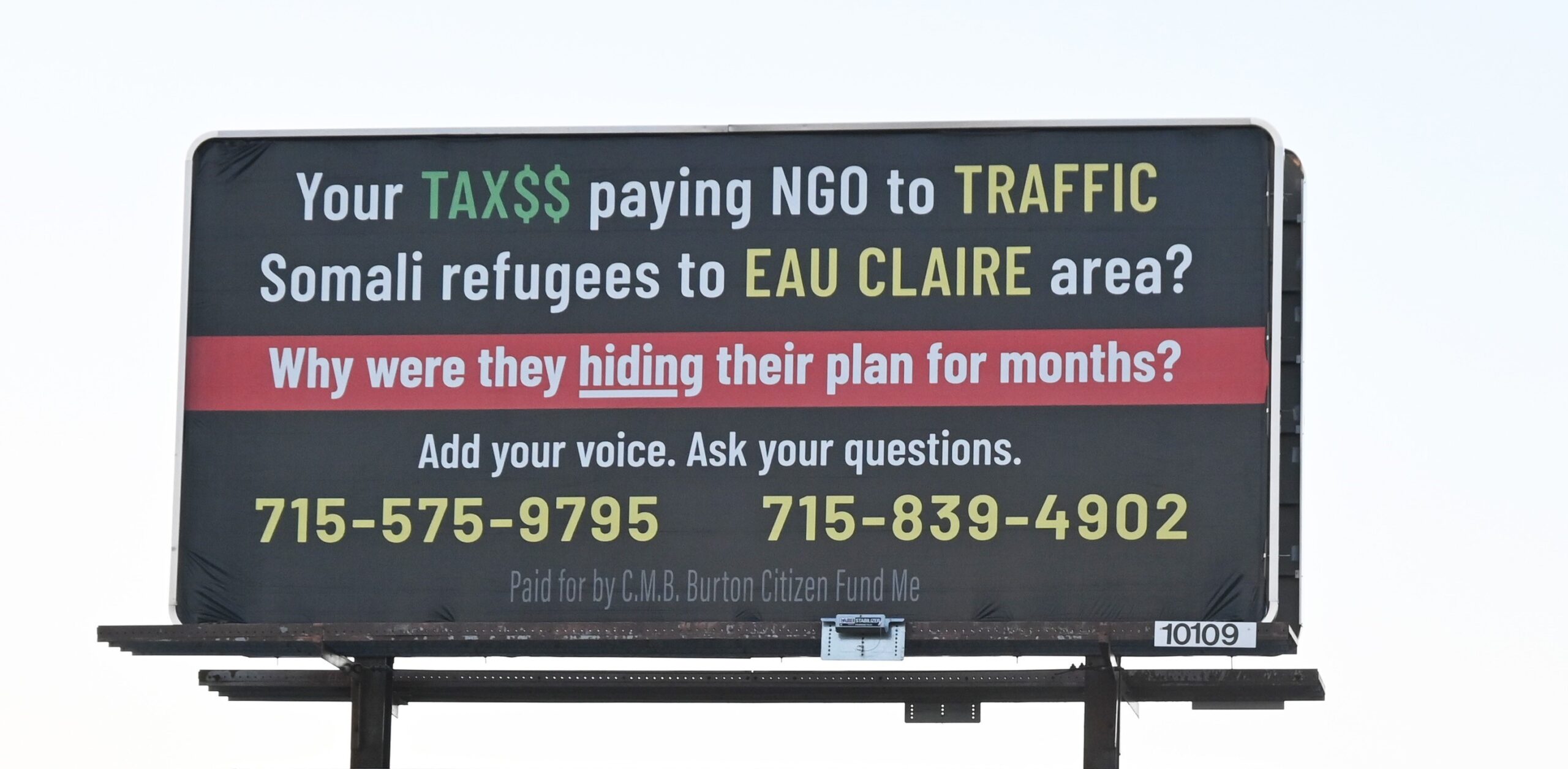

When news of the Eau Claire resettlement plan broke last fall it was met by anger and protests fueled, in part, by false claims from conservative websites alleging there would soon be 3,000 Somali refugees coming to the city. A billboard went up accusing World Relief and city leaders of using tax dollars to “traffic Somali refugees” to Eau Claire and keeping the plan secret.

World Relief Vice President of Advocacy and Policy Matthew Soerens told WPR there was nothing secret about the resettlement plan and the nonprofit doesn’t know where refugees will be coming from until notified later by the federal government. He said the Democratic Republic of the Congo was the top country of origin for resettlement in 2022, and it’s unfortunate to see the anti-Somali sentiment.

“It’s based on rumor, and frankly, on a particular hostility to refugees from certain countries of origin, or maybe from particular religious backgrounds,” Soerens said.

Mohamed said he understands some of the concerns from some in Eau Claire, but he knows firsthand that refugees are vetted for years by the United Nations, refugee mission groups and U.S. agencies like the Department of Homeland Security while they wait in refugee camps, like he did, around the world.

“You may say that, ‘Oh, this is my place, this is my county, this is my area,’” Mohamed said. “But I will say no, you came one time. You only came before me. And I came after you. That doesn’t give you more rights than me. But we are all Americans at the end of the day. And we all deserve respect.”

Anti-refugee sentiment in Eau Claire fueled by false claims

In October, the Eau Claire County Board rejected a resolution aimed at pausing the resettlement until the city and county could assess whether it could afford new residents, who may require public assistance.

The refugees would make up around one one-tenth of a percent of the city’s population. There was an overflow crowd during public comments with the majority opposing the resettlement. The board rejected the resolution, but the heated discussion was a window into how residents perceive the issue.

County resident Chris Connel, who unsuccessfully ran for state office as a Republican in 2022, urged legal action to block the refugees. He concluded his remarks with a mocking statement directed at the nonprofit.

“I would just like to say to World Relief: I don’t want the world to relieve themselves on me,” Connel said.

Some voiced concerns about refugees from Somalia. So far, none of the arrivals in Eau Claire have come from Somalia. Mohamed and World Relief have said if they do, they’ll likely be reunited with family in the Barron area. Those who have come to Eau Claire are from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, which is a predominantly Christian nation.

“You may say that, ‘Oh, this is my place, this is my county, this is my area.’ But I will say no, you came one time. You only came before me. And I came after you. That doesn’t give you more rights than me. But we are all Americans at the end of the day. And we all deserve respect.”

Isaak Mohamed

The anti-refugee comments at the meeting felt personal to Eau Claire Area Hmong Mutual Assistance Association Executive Director Tru Vue, who came to Wisconsin as a refugee early in her life. Her voice shaking with anger, Vue told the County Board her family was among thousands who fled to the U.S. after helping U.S. soldiers during the Vietnam war.

“There was a genocide against the Hmong people,” Vue said. “We lost men. My uncle passed away. My other uncle who was a baby at the time, my grandmother had to give him opium, so then he could be quiet and sleep. But in fact, what happened was he overdosed and he died. We sacrificed so much.”

Republican lawmakers introduce legislation aimed at slowing, stopping influx of refugees to Wisconsin

Republican lawmakers quickly responded to the local anger over the Eau Claire resettlement plan and brought the issue to the Wisconsin Capitol and U.S. Congress.

In January, State Rep. Karen Hurd, R-Fall Creek, introduced a bill that would require any local government employee contacted by either the federal government or a resettlement agency about a refugee placement to notify all other local governments within a 100-mile radius.

Public hearings and resolutions of support or opposition would also be required. Hurd said the bill was needed because Eau Claire’s city manager didn’t inform Eau Claire County Board members about the World Relief plan soon enough.

Hurd said the bill wasn’t about blocking resettlements, acknowledging the federal Refugee Act of 1980 means “they’re going to come whether we like it or not.” Still, Hurd said local elected officials need to be notified so they can confirm whether they have resources for new arrivals.

On the floor of the Wisconsin Assembly, Democrats accused their Republican colleagues of racism, xenophobia and “legislating hate” with the bill.

In the end, the bill passed the GOP-controlled legislature on a party-line vote but was vetoed by Democratic Gov. Tony Evers.

At the federal level, U.S. Reps. Tom Tiffany and Derrick Van Orden, both Republicans, tried to overhaul the resettlement process in February. Their bill, called the Community Assent for Refugee Entry Act, would give states and even local governments the power to reject future refugee placements. The legislation hasn’t had a hearing in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Acceptance of refugees requires communication, time

Not all proposed refugee resettlements face the kind of backlash seen in Eau Claire and St. Croix County. In 2021, nonprofit resettlement agency Ethiopian Community Development Council opened a branch office in Wausau and assisted 160 refugees in its first year.

Janice Watson, the office’s executive director, told WPR she hasn’t heard anything negative about their work. She said the group hosts quarterly meetings and welcomes other nonprofit assistance organizations and local elected officials to participate in discussions about the number of new arrivals and challenges they face acclimating to their new lives in America.

“So, talking about housing, employment, it’s a variety of things,” Watson said. “And then our partners can also report out, to talk about what’s happening, how the refugee families are transitioning, all of that stuff.”

Wooksoo Kim is a professor with the University of Buffalo School of Social Work in New York, who co-founded the Immigrant and Refugee Research Institute. She said there can be a lot of factors behind opposition to refugees including bias, racism or a general fear of the unknown. The cure for that, she said, is regular communication from resettlement organizations about the benefits refugees are bringing with them when they arrive.

“So, when you get the chance to meet refugees as fellow community members, rather than seeing them as an abstract concept that will bring you fear, people are more likely to embrace the refugees over time, Kim said.

Kim said sometimes it can take generations.

“It’s all about making it real for people and showing them firsthand experiences in individuals,” Kim said. “And sometimes, we have to start from early childhood education to make the kids feel more comfortable with differences like cultural exchange programs.”

At the end of April, World Relief held its first quarterly meeting in Eau Claire.

Felisha Deering is one of the prospective World Relief volunteers hoping to assist new arrivals. She said she feels called to help because of her Christian faith and the Bible’s call to love your neighbor means what it says.

“And I would also say that to my fellow Christians, if you are having those thoughts, to just remember that Christ did everything in love, and that he did call us to take care of the widows, the orphans, the refugees,” Deering said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.