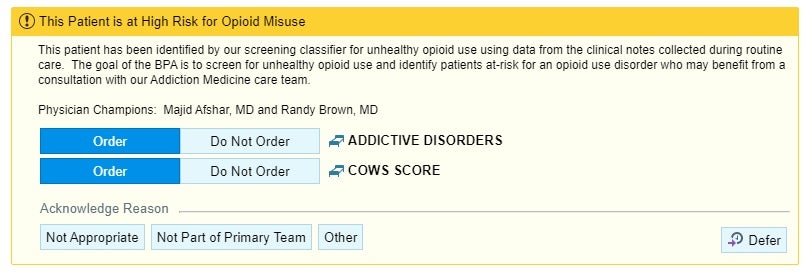

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison School of Medicine and Public Health have shown a new AI tool was successful at flagging patients at risk of opioid addiction and at reducing hospital readmissions.

The AI screening tool processes information from a patient’s electronic health record, including clinical notes from providers and the patient’s medical history. It alerts a provider when a patient is at risk of opioid misuse and suggests a consultation with an addiction medicine specialist or treatment for withdrawal symptoms.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Dr. Majid Afshar, lead researcher and UW-Madison professor, said the tool is designed for providers that may not be thinking about addiction regularly.

Emergency room physicians who frequently treat overdose patients may not need the prompt to direct someone for follow up. But Afshar said patients struggling with opioid use disorder frequently get other types of care.

“People that are coming in with wound infections, pneumonia, asthma exacerbation, a broken bone that may be related to their substance use,” he said. “The substance use or opioid use disorder may be a secondary problem. The focus in the hospital is kind of take care of that primary problem, get the patient treated and move them on.”

But Afshar said treating the underlying problem of opioid use disorder leads to better outcomes for the patient and less spending on health care.

A clinical trial that was funded by the National Institutes of Health found UW Health patients who were identified by the AI tool and received an addiction medicine consultation were 47 percent less likely to be readmitted to the hospital within 30 days. That’s compared to patients from previous years who received addiction medicine consultations based on a provider’s referral.

Afshar said the study also found the AI-prompted consultations happened later during a patient’s hospitalization than those in previous years.

“A lot of times, people forget about those kind of underlying problems after they first ask them, and they don’t come back to them,” he said. “We think that (AI-driven) nudging was happening closer to discharge, when patients might need help to kind of identify additional care outside of the hospital or get harm reduction services.”

He said the research also showed a slight shift in the types of patients receiving consultations once the AI tool was deployed. Afshar said it identified more underserved patients, like those who are uninsured or who rely on Medicaid, who generally have high rates of hospital readmission.

The screening tool, which continues to be used by UW Health providers, could be just the first step in how AI can help providers better respond to the national problem of opioid addiction. Afshar said he believes the technology could also be developed to assist providers in diagnosing opioid use disorder.

“If we can give them an AI assistant to help guide them to make the decision with the patient to want to start treatment, I think that’s the next step,” he said. “Especially in low resource settings, where maybe the clinicians are overwhelmed or they don’t have the addiction specialist to consult.”

But the future of this type of research is uncertain. President Donald Trump’s administration has worked to cut millions of dollars in NIH funding and thousands of federal workers across the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Afshar said he personally believes funding clinical studies and collaborative research is the best way to ensure new technology is incorporated into patient care in the best way possible.

“AI can be a powerful tool, but it could be a power for good or bad,” he said. “Really the way to distinguish that is we need science. We need evidence-based medicine.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.