When around 3 million Wisconsin voters cast ballots in a November election that could again decide the future of the country, it will be a handful of people — Wisconsin’s county and municipal clerks — who keep the wheels of democracy turning.

Wisconsin, where four of the last six presidential races have been decided by less than a percentage point, is one of a handful of swing states expected to decide whether President Joe Biden or former President Donald Trump returns to the White House. Since 2020, its elections have been under intense scrutiny.

New laws, court cases that could again change how people vote absentee, and recent changes to the state constitution mean that the minute details of election administration are seemingly always in flux.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

In Wisconsin’s decentralized administrative system, clerks — from the largest cities to the smallest towns — are charged with staying on top of an ever-changing system and getting a ballot into voter’s hands.

They’ve also become the face of a system that some portion of voters still don’t trust, four years after a concerted and ongoing effort to undermine faith in an election that saw Trump narrowly lose to Biden.

Facing harassment and barraged with misinformation, many have stepped away from election work. Despite the challenges, new clerks have filled their shoes.

Take Anastasia Gonstead. This November will be her first time administering a general presidential election since becoming a clerk in January of 2023. She started out as clerk in the Dodge County city of Mayville, then switched to the same job in the Washington County village of Jackson.

“I didn’t really have time to be concerned” about what faces election workers, she said. “I had started in January, and my first election was in February, so I had to hit the ground running.”

Gonstead is one of nearly 2,000 clerks — 1,850 at the municipal level, and 72 county clerks — who administer Wisconsin’s elections.

While county clerks are partisan, municipal clerks are not. They’re hired civil servants who also do things like take meeting minutes and coordinate local liquor licensing. Some have deputies and extra staff. Some are just part-time employees. Some are in a hybrid role that also includes being their community’s treasurer.

All are juggling competing community needs, a packed election calendar and an ever-changing legal landscape as they prepare for an August statewide primary and a closely watched national election in November.

“They’re under more scrutiny in a presidential race, when Wisconsin will be one of the key swing states in the Electoral College,” said Barry Burden, who directs the Election Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “An error, a small mistake, or a delay caused by a clerk can lead to suspicion or misinformation or even conspiracies about something that’s going wrong in the election.”

Clerks have spent months getting ready for Election Day

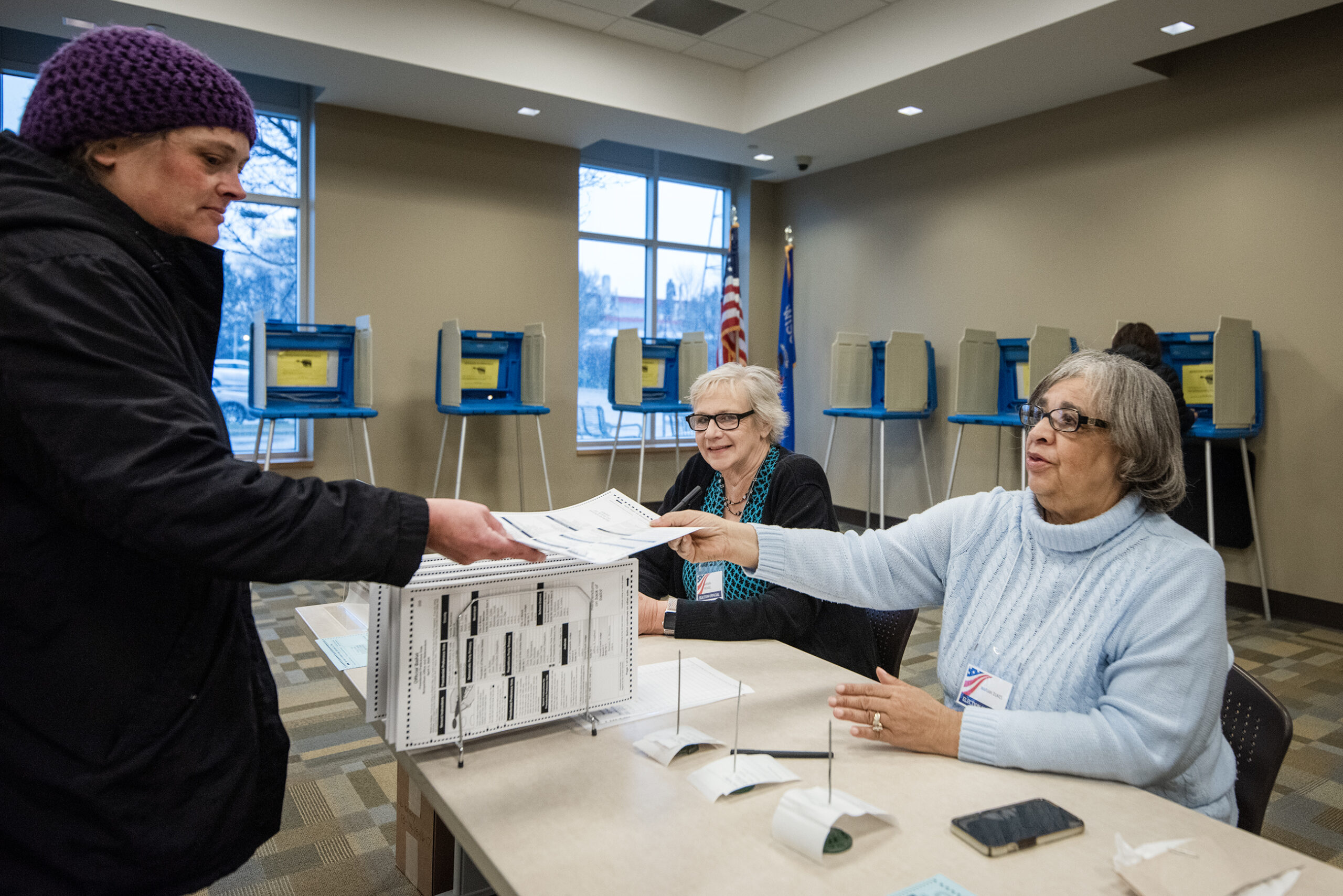

Months before a voter arrives at the ballot booth, clerks have paved the way for that process.

“What a lot of people don’t realize for clerks is, our work is already underway,” Gonstead said.

Clerks train poll workers and coordinate the special voting deputies who go into assisted living facilities. They order the ballots and the envelopes, and check them once they come in. They test the tabulators and hold public tests. And at the end of Election Night, clerks verify and post the results.

Each of these tasks is according to the law, with guidance from the Wisconsin Elections Commission. Some of their duties — like the public tests of voting equipment — are meant to garner public confidence.

“Clerks’ offices work really, really rapidly to get that stuff out,” Gonstead said. “A lot of it is looking at that schedule and picking out those little things: ‘What can I do here, what can I do there, to make my life easier when it’s all go, go, go?’ Because it comes hot and heavy.”

Clerks must also stay on top of an election system that’s often in a state of flux.

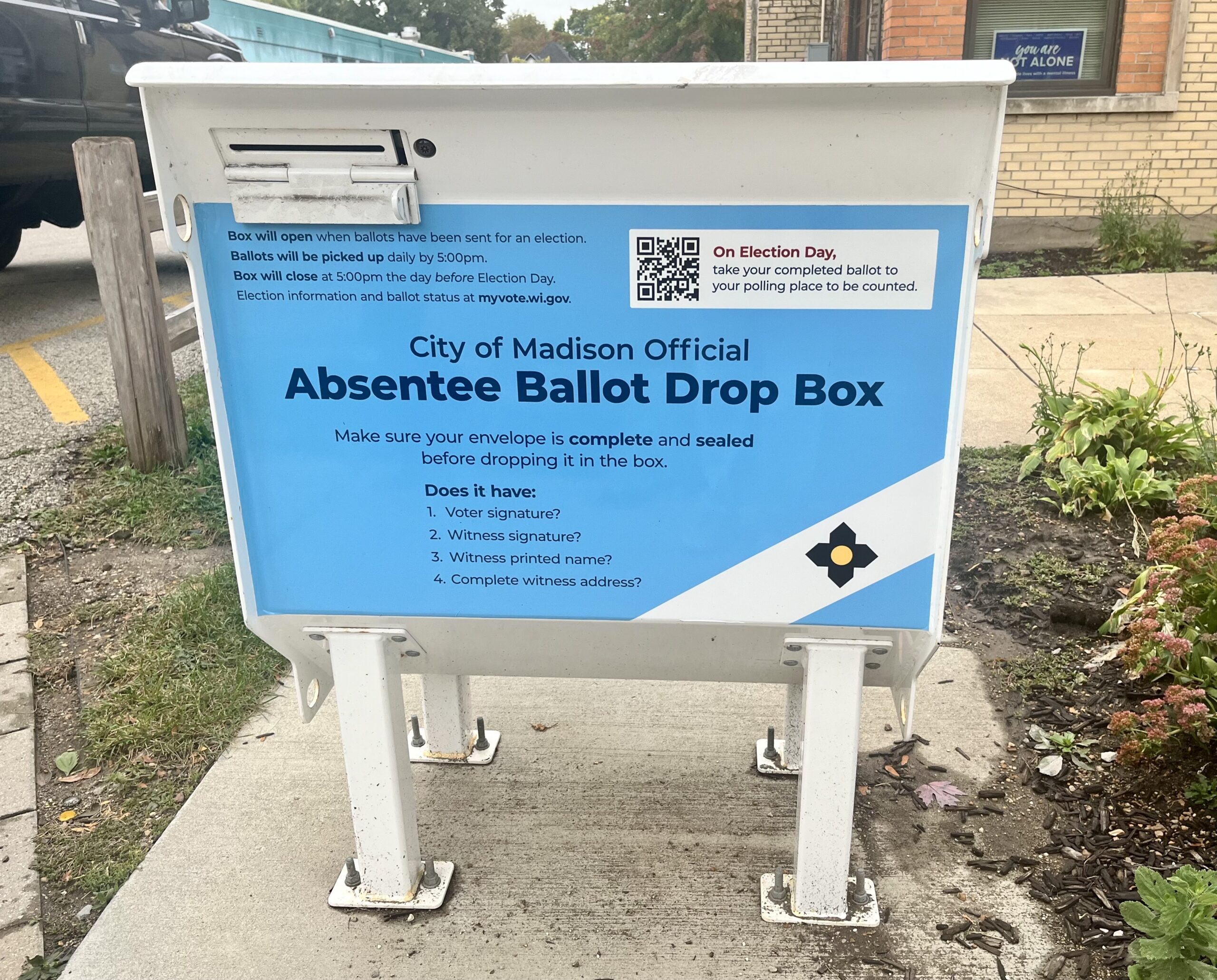

Barely four months out from the presidential election, Wisconsin courts are still considering the legality of absentee ballot drop boxes, which were widely used in the 2020 election, then banned by the Wisconsin Supreme Court’s conservative majority in 2022. The same court, now under a liberal majority, is considering a lawsuit that could reinstate drop boxes ahead of the 2024 election.

In recent weeks, a Dane County judge ruled that voters with disabilities may use email to request absentee ballots, and Attorney General Josh Kaul issued an interpretation of a constitutional amendment, passed in April, explaining that clerks may still use private vendors for jobs like ballot printing.

It is up to the clerks to materially respond to these changes. If the Dane County ruling holds, clerks will have to establish new systems for responding to the emailed ballot requests, for example. If drop boxes are reinstated, some clerks will work with public works employees to haul the banned bins out of storage and reinstall them. Some changes mean re-training poll workers or printing new signs.

Such are the small details that go into administering a Wisconsin election. But the constant shift in rules can make it “hard to communicate with the public,” said Scott McDonell, a Democrat who has served as Dane County clerk for a decade.

“It does sort of cause a crisis of faith a little bit, these constantly changing rules, and it feeds the narrative that the rules change … it’s being gamed,” McDonell said. “It really isn’t. But it doesn’t help at all.”

Since 2020, pressure has been turned up

While clerks don’t make the laws for voting, as the faces of Wisconsin’s election system, they’re often the first to hear about it when people are unhappy.

That’s become more common since 2020, when Trump narrowly lost to Biden but falsely claimed that he won. Harassment and threats against election workers across the country escalated, as widespread conspiracy theories spread about alleged fraud and other misdeeds.

According to research by the Brennan Center, a liberal think tank, about a sixth of election officials nationally have been threatened, and three-quarters said threats have increased.

In 2021, the U.S. Department of Justice launched a taskforce to investigate threats against election workers. About 2,000 threats have been reported nationwide, with fewer than twenty cases prosecuted. A mob in Georgia allegedly came to the home of an election worker on Jan. 6, 2021. Last fall, elections offices in several states, including Nevada, Oregon and California received letters seemingly laced with fentanyl.

Wisconsin has not faced such dramatic incidents, but has not escaped the spike in tensions. According to a 2021 survey from the UW-Madison’s Election Research Center, municipal clerks, especially those working in larger communities, saw an uptick in “threatening or hostile messages” received during the 2020 election cycle.

Workers faced acute stress in swing states. According to a 2021 Reuters investigation, more than 40 election workers in battleground states received threats of violence.

But the haranguing doesn’t have to reach that dramatic level to affect people trying to do their jobs, said McDonell.

“It isn’t the headline-stealing threat. It’s these constant, you know, maybe a little more mundane harassment,” he said. “It’s the kind of thing that says, like, ‘I could make more (working) at Costco.’”

According to the Wisconsin County Clerks Association, about 40 percent of county clerks will be administering their first presidential elections this fall, after unprecedented turnover following the 2020 election. Such data isn’t available for municipal clerks, but Burden said that the standard turnover that always follows a presidential election “appears to have escalated after 2020.”

When those clerks leave, some amount of institutional knowledge disappears with them.

“Having people who are seasoned and experienced who had been through some election cycles, who know their voters and know the systems is really helpful,” said Burden, of UW-Madison. “It’s just one kind of certainty or building block that you can have established before we get into the busy campaign season.”

Clerks use community roots in fight against misinformation

While conspiracy theories about elections can come from anywhere, what works in clerks’ favor is that they’re actually members of their communities, which can heighten trust.

In Addison, a small town in Washington County, Wendy Fairbanks became the clerk in July of 2021.

“The election process is stressful, definitely. But it’s more (that) we know the responsibility that’s put on us to do it correctly. And we all strive to do that, to our best ability,” she said. “And there’s so much controversy in society these days, and we just want people to be at ease knowing that their votes count, and that it’s going to be accurate.”

She said the community holds listening sessions, and sometimes people bring “their conspiracy theories.”

“But on the most part, the people that I see that come into the polls, they’re pretty confident in the process,” she said. “They’re able to see what happens, they’re able to talk to their neighbors.”

Brennan Center research has also found that misinformation is a persistent thorn in the side of election officials. About three-quarters of election workers surveyed said misinformation on social media “has made their job more difficult,” and half said it made their job “more dangerous.”

Being a trusted source of information is important to Toya Harrell, another municipal clerk preparing for her first presidential election. She began working in Shorewood, a suburb of Milwaukee, in November of 2021.

“I love being the person that is giving you the real information, instead of everything you heard on social media, or that you heard someone say they saw happen in a different state,” she said. “I’m that person that assures you.”

I love being the person that is giving you the real information, instead of everything you heard on social media.

Shorewood Municipal Clerk Toya Harrell

According to research by the Secure Democracy Foundation, a national group that seeks to build voter confidence, Wisconsinites largely have faith in their elections. About 73 percent of Wisconsin voters trust the state to administer the election fairly. That includes a majority of both Republicans and Democrats, although Republicans are less trusting than Democrats.

That same research shows that Wisconsin voters tend to trust their own local officials most of all, and more than 80 percent believe in the existing system of checks and balances administered by local election officials much more than they trust state officials or the Legislature.

Gonstead, the clerk at the village of Jackson, is returning to her former post in her hometown of Mayville. In her final weeks in Jackson, she sent out absentee ballots for the August primary, and will leave behind a neatly organized — and securely locked — elections closet for her successor.

Although the details of the work changes between communities, the overarching role does not.

“We’re in a nation where we have the ability to cast our vote, to have our voice be heard. I wish more people took advantage of it, to be quite honest,” she said.

“But to know I’m there, and I can say, ‘In the community I work in, my elections are held properly, per law. Everyone who wanted to cast a vote and was legally able to was able to on that day’ — it’s fantastic.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.