There’s a new kid in town — and it’s 430 million years old.

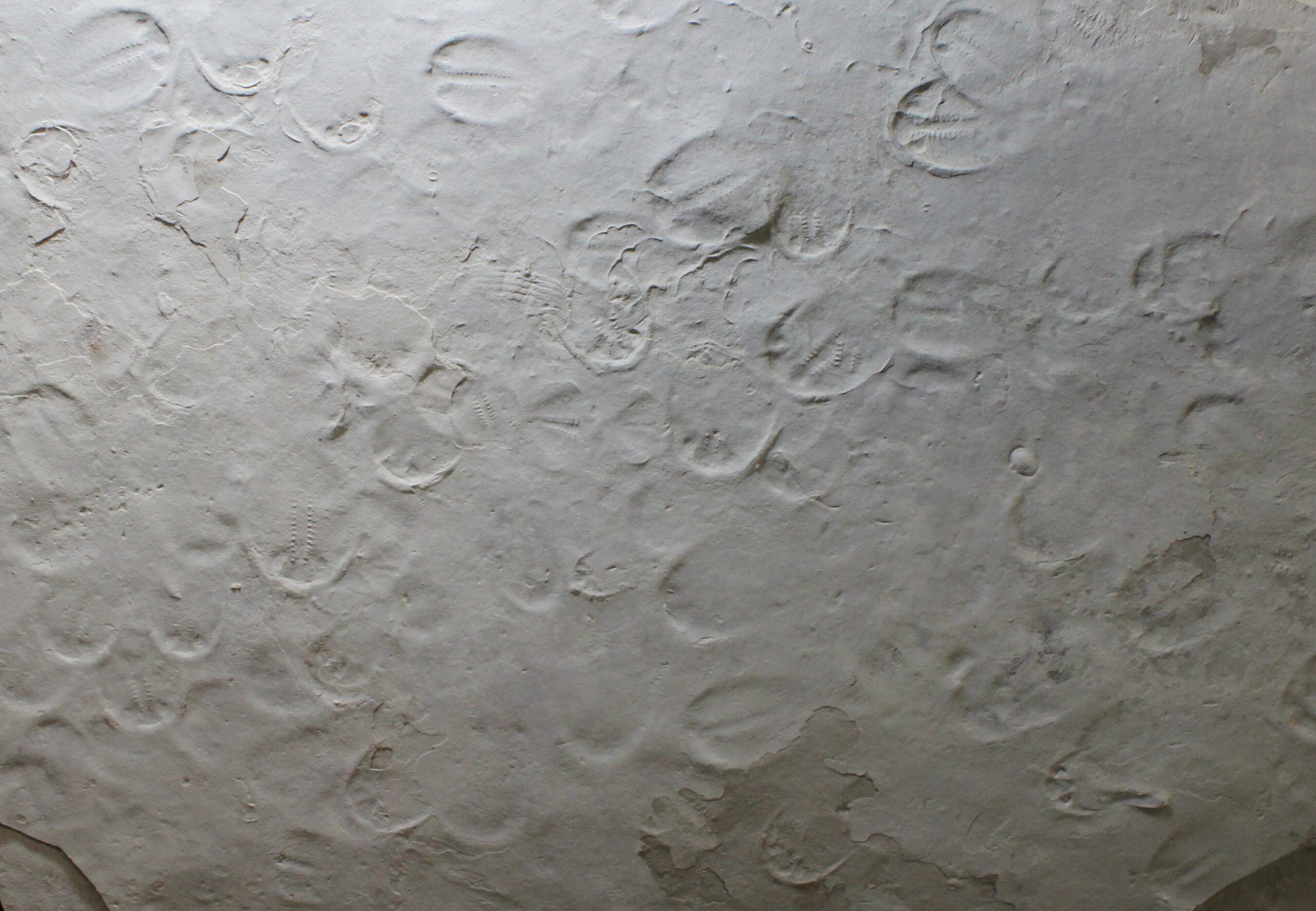

Wisconsin paleontologist Kenneth “Chris” Gass recently named Waukeshaaspis eatonae, a unique species of trilobite first discovered at a fossil site in Waukesha in 1985 and studied almost 40 years later by Gass and another scientist.

Trilobites are a crab-like species of marine arthropod that mostly lived in shallow waters from the Cambrian Period (about 520 million years ago) until their extinction at the end of the Permian Period (about 250 million years ago).

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Trilobite fossils have been found all over the world, but they have a special history in Wisconsin, where they are the official state fossil.

Waukeshaaspis eatonae is one of many ancient species found in the Waukesha Biota, a rare fossil site that scientists discovered in 1985.

The biota brought new attention to Wisconsin as a paleontological hub because of its preservation of soft-bodied parts in fossils from the early Silurian period (approximately 437 million years ago).

“Instead of just shelly animals like clams and brachiopods and snails and things like that that have shells that fossilize easily, we’re seeing skin, eyes, legs, internal organs in Waukesha, which is extremely rare,” Gass told WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

Many of the specimens collected from the Waukesha Biota are now housed at the University of Wisconsin Geology Museum in Madison. Some of them — including Waukeshaaspis eatonae — sat in a drawer for decades before receiving the attention of scientific researchers.

“There’s just so much in the biota that it got put aside because it’s a trilobite, and trilobites are fairly common as a whole,” Gass said.

Before getting its name, Waukeshaaspis eatonae was briefly mentioned in a 1985 paper about the fossils found in the Waukesha Biota, but Gass said it was “not described, not named, not diagnosed or compared with anything else.”

“It was about time that somebody did that,” he added.

Recently, Gass teamed up with Enrique Alberto Randolfe, a scientist from Argentina, to research the trilobite. They found that it was unique for having an indentation at the back end of its body rather than the typical pointed spine of most other trilobites of its family.

Last month, Gass and Randolfe made the new name official by publishing it in the Journal of Paleontology.

Gass said Waukeshaaspis is named after Waukesha, the only place where this genus of trilobite is found. The species name, eatonae, is named after Carrie Eaton with the UW Geology Museum.

“She’s the curator and did so much for the research that I’ve done in this and in other aspects of the Waukesha Biota that it just made perfect sense to name it after her,” Gass said.

This new naming is one small part of a larger effort to dig into Wisconsin’s rich geological past.

Gass said that when he was a kid, Wisconsin was a “drive-through state, paleontologically.” But now, it’s seen as a treasure trove of fossil research, thanks to major discoveries like the Waukesha Biota and, more recently, Blackberry Hill in Marathon County.

“It’s an exciting time for paleontology in Wisconsin,” Gass said.

‘I kind of feel like I won the lottery’

When Eaton learned that a fossil had been named after her, she said it was a “huge surprise.”

“I feel incredibly honored, especially because so much of what I do in my job is typically done behind the scenes,” Eaton told “Wisconsin Today.” “It’s not the work that is necessarily put to the forefront or makes the news, but it’s the kind of work that makes all of that stuff happen.”

Eaton started her job as the curator of the UW Geology Museum in 2009. At that time, a large group of specimens from the Waukesha Biota collection had recently been returned to the museum after being out on loan to researchers around the country for many years.

Eaton said she “immediately started diving in” to organize, catalog and take images of the more than 2,000 specimens in the collection to make it more accessible for researchers.

“One thing I’m particularly proud of is that in the 15 years that I’ve been here as curator, because of that work, this collection has yielded … more than a dozen scientific papers, many of which were describing brand-new species coming from this really unique unit right here in our home,” she said.

The latest of these is Waukeshaaspis eatonae. For most of history, newly identified species have been named after men. But that’s changing, Eaton said.

There is a growing movement to name species after places or geological features rather than paying homage to a specific person. Some scientists are also opting to use a language other than Latin for scientific nomenclature.

Eaton’s colleague Dave Lovelace, a paleontologist at the geology museum, is in the process of naming new species he is finding in Wyoming in the Native languages of the region.

“He’s been working with the tribal councils of the Shoshone and the Northern Arapaho to name new species in their languages, which is both honoring the place where those objects were found and also the people who were there before us,” Eaton said. “I think the more that we can name these new species in a global and more inclusive context, the better it is for science in general.”

While trilobites are a bug-like, “creepy crawly” species, Eaton said she is proud to have one named after her.

“If I had to pick a fossil from Wisconsin’s ancient past, a trilobite is about as good as you could get,” Eaton said. “They were one of the earliest forms of very complex life to emerge … and they were also one of the most successful organisms. They were around for 270 million years — that’s 100 million years longer than dinosaurs. If we could get kids to love trilobites as much as they love dinosaurs, I think that would be a win.”

“I think they’re fantastic organisms, and I think we should appreciate them more,” she continued. “I kind of feel like I won the lottery getting a trilobite named after me.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated Dec. 10 with more precise information about the trilobite’s spine.