In 2010, Wes Arnett had a life crisis.

His father died of cancer. He became an entrepreneur opening and relocating a business. He had four children under the age of five and his 20-year marriage was in turmoil. That is what lead him into a “downward spiral” of substance use disorder.

“Today, I call this the WTF,” Arnett said. “What’s the function? … Our behaviors are driven to serve a function.”

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Now, as a state-certified peer-support specialist and in recovery for more than four years, he works at the newly opened UW Health Compass Program in Madison. He tells patients this story as he helps them navigate the complexities of substance use disorder with his first-hand experience.

“I’m in the army of hope,” he said. “That is really what we do is we offer hope to people.”

The clinic opened in January and specializes in opioid use disorder. It offers walk-in appointments and free services to people with or without insurance. Patients can get prescription medication for opioid use disorder and medical treatment like basic wound care, family planning or hepatitis C treatment.

It also offers peer support from people like Arnett who can connect patients with community services like housing, transportation, vocational training or food.

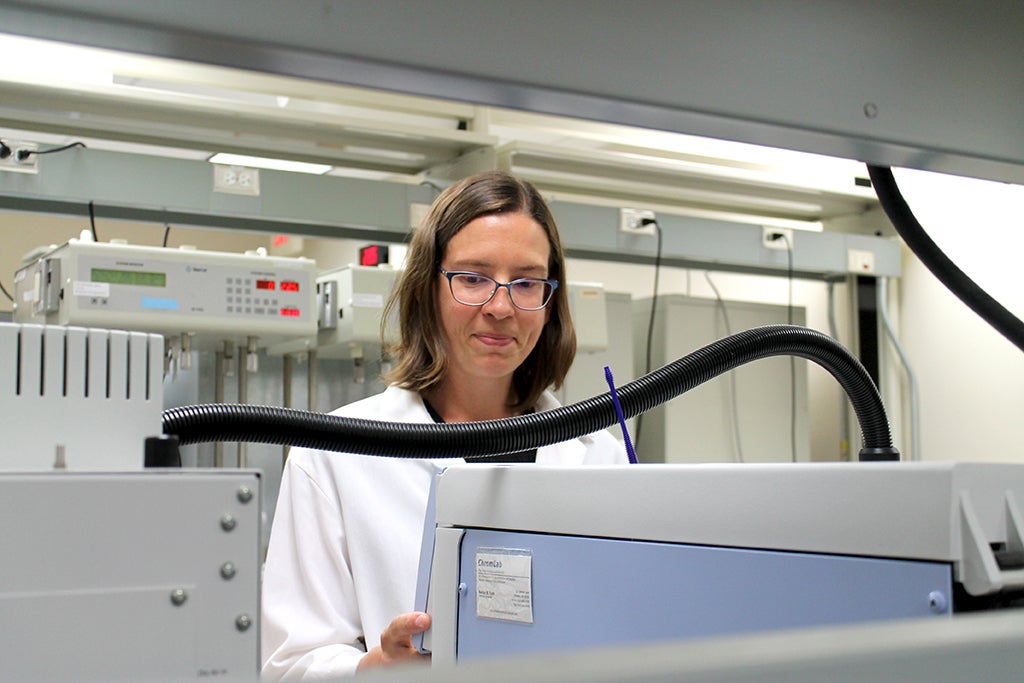

Compass is the only clinic in Dane County that offers this combination of services, according to Compass Medical Director Dr. Elizabeth Salisbury-Afshar and the state Department of Health Services.

“We think of ourselves as a safety net,” Salisbury-Afshar said. “We’ll offer everything that we can, and if there’s something that someone needs that we can’t offer, our goal is really to help them figure out where they can go.”

Follow-up care is necessary beyond emergency room visits

The clinic opened, in part, as a response to Madison Emergency Medical Services and local emergency rooms offering Buprenorphine, a prescription medication that treats acute opioid withdrawal.

Salisbury-Afshar said although the medication is necessary and saves lives, it requires follow up.

For example, an emergency room doctor or an ambulance responds to an overdose at 2 a.m. She said after the patient receives Buprenorphine there is a list of challenges that often continue beyond that moment. What insurance does the patient have? Which treatment programs have waiting lists? Does a medical clinic have an opening?

“To give someone a dose of medicine once but without any follow-up plan isn’t going to be likely to help someone very much,” she said. “But to be able to give them medicine and have confidence they have a place to follow up is the system of care, largely speaking, that we’re all aiming for.”

Housing, jobs, mental health aid are paths to treat substance use

Salisbury-Afshar said the clinic is aiming to address a service gap in Dane County for people who use substances. But it is just one piece in addressing the opioid epidemic.

Last year, 1,372 people died of an opioid overdose in Wisconsin, according to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That is a slight decrease from the year prior. For the first time in five years, national drug overdose deaths related to opioids fell in 2023.

She said every one of those deaths is preventable.

“It’s housing. It’s educational opportunities. I think it’s living-wage jobs. I think it’s treatment access and not just substance use disorder treatment but mental health treatment,” she said. “It’s figuring out ways to interrupt cycles of trauma and poverty because all of these factors are contributing.”

Arnett, the peer support specialist, said he wants people who use substances to know that all the shame, guilt and loneliness they might be feeling is something he has experienced.

But now after four years and five months in long term recovery he hopes people with substance use disorder can look at him as an example.

“I want them to see somebody and go, ‘Hey, you’ve gone through this and look, you’ve come through the other side,’” he said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.