For Jennifer Boehme, the Great Lakes floor holds a variety of treasures waiting to be rediscovered, from sinkholes to shipwrecks.

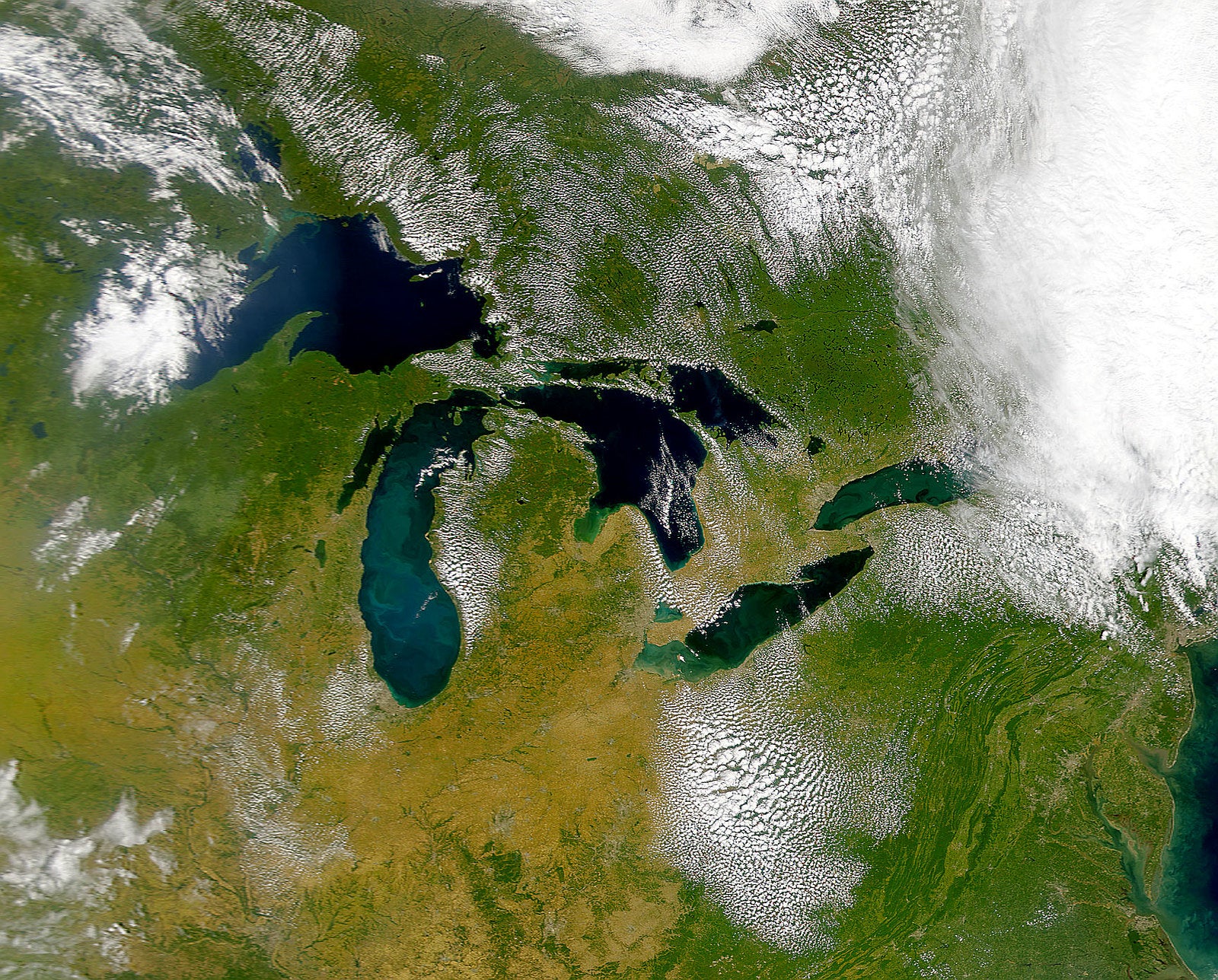

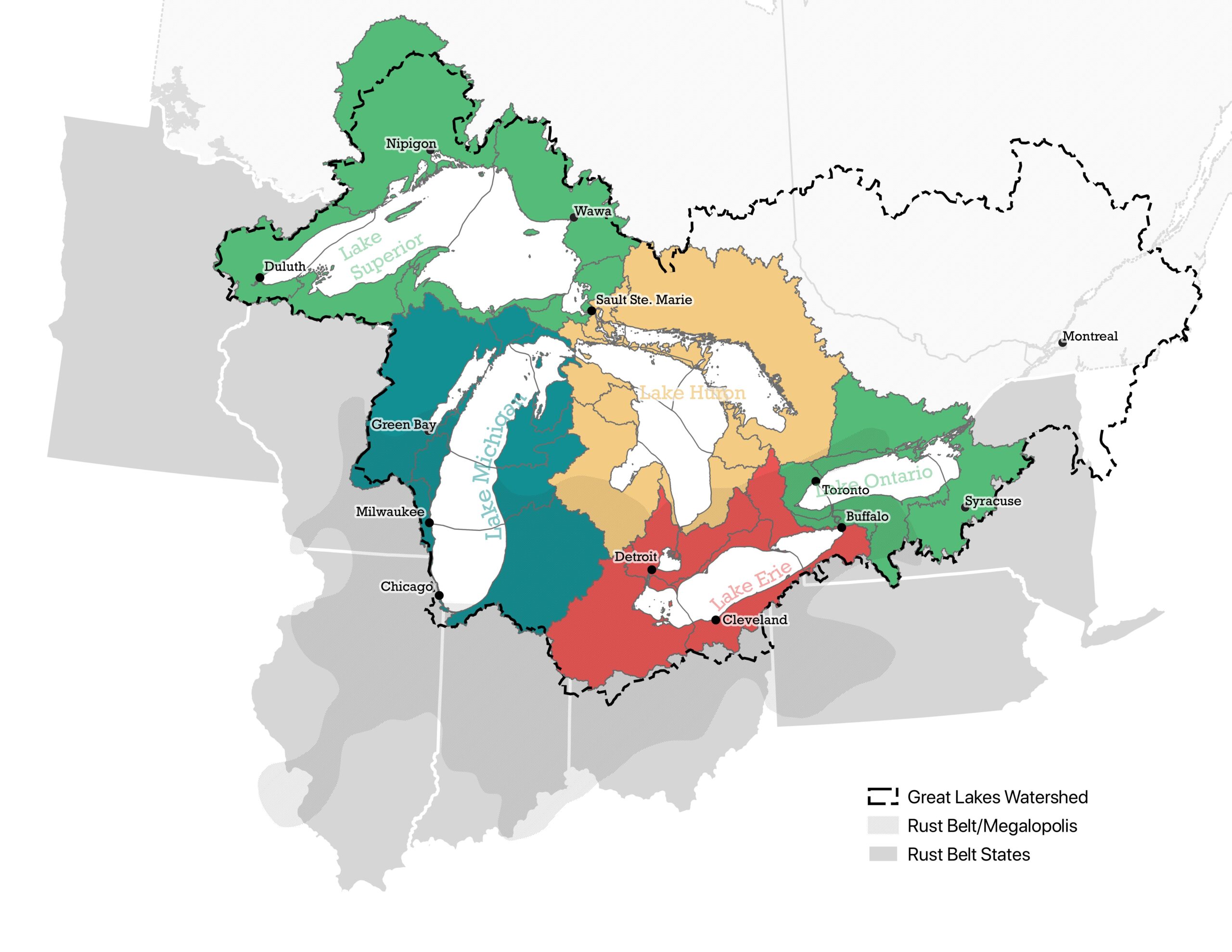

But coastal safety is the primary factor driving her work with the Great Lakes Observing System, a Michigan nonprofit working to fully map the bottom of the Great Lakes. The lakes span 94,250 square miles or nearly the size of the state of Oregon.

Despite humans’ long history of using the lakes for water, transportation and sport, scientists say little is known about what lies deep below the surface.

Boehme said the mapping initiative, which has been dubbed Lakebed 2030, supports ongoing efforts to make the region more resilient to climate change.

“It identifies areas prone to erosion, flooding or damage from shifting lake bed sediments that are caused by extreme weather events. The Great Lakes are experiencing more frequent and more severe storms in recent years and that causes increased erosion,” said Boehme, the group’s chief executive officer. “This is something that can be very damaging to coastal communities, private and business infrastructure, if it’s not understood and managed effectively.”

The amount of rain falling as the heaviest one percent of storms has increased by 35 percent over a 66-year span. The severity of storms is complicated even more by the loss of ice during the winter, which typically serves as a buffer against waves generated by severe storms. Boehme noted Lake Superior is warming the fastest among the Great Lakes.

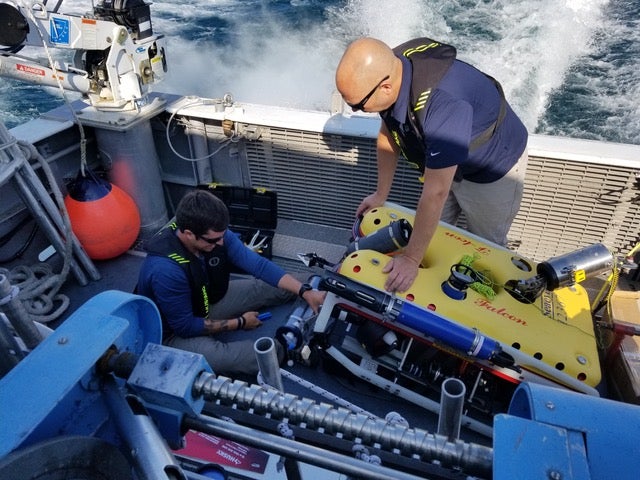

Amid those changes, the Great Lakes Observing System began the concerted mapping effort in 2019. At the time, only 12 percent had been mapped to modern standards. Since then, the nonprofit has mapped a total of 15 percent working with partners, highlighting the need for further collaboration and funding.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

Earlier this year, Michigan Republican U.S. Rep. Lisa McClain introduced the Great Lakes Mapping Act, which received bipartisan support from lawmakers like Wisconsin Democratic U.S. Rep. Mark Pocan. The bill would task the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, or NOAA, with conducting high-resolution mapping of the lakebeds with partners, as well as provide $200 million for the work.

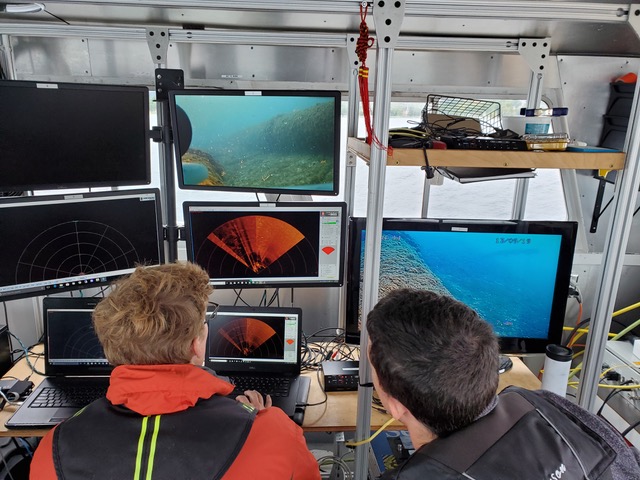

Right now, a patchwork of maps have been created through singlebeam sonar technology that can be found on many fishing boats. Boehme said more modern methods exist, including the laser-based tool known as LiDAR. The technology could be used to create a three-dimensional view of the bottom.

With thousands of shipwrecks in the region, Boehme said the mapping effort also provides an opportunity to rediscover the Great Lakes maritime heritage. The Michigan nonprofit has been working with the Wisconsin Shipwreck Coast National Marine Sanctuary to install buoys near shipwrecks along the coast of Lake Michigan.

Russ Green, the marine sanctuary’s superintendent, said most of the sanctuary’s roughly 1,000 square miles have already been mapped. The sanctuary includes 40 nationally significant shipwrecks.

“They’re important historic sites, and they just tell an amazing chapter in our nation’s history,” Green said. “But beyond that, the mapping helps us potentially find these sites, so we can explore and find new shipwrecks and other cultural resources.”

He said the mapping effort revealed dozens of depressions on the lake bottom that extend for about 30 miles. Green said the sanctuary received a $315,000 grant from NOAA to find out more about them, as well as shipwrecks recently discovered but not yet explored.

Mapping the lakes is also crucial for the region’s environmental stewardship and economic activity, Boehme said. The Great Lakes provide drinking water for nearly 40 million people.

Ed Bailey, director of program and portfolio development for Northwestern Michigan College, said the mapping effort will provide a better understanding of fish habitats and potential hazards.

“From a priority funding perspective, it needs to be elevated,” Bailey said. “The number of people that live around the Great Lakes, number of individuals that use the Great Lakes for their drinking water on a daily basis, and the economic impacts the Great Lakes have on the U.S., it needs to be a priority.”

However, legislation has not advanced in Congress. Rep. McClain plans to reintroduce the bill in the next session if it doesn’t pass.

“The Great Lakes generate [$]6 trillion to America’s GDP and support over 51 million jobs, yet we have barely scratched the surface of understanding the depths of the lakes,” said McClain in a statement. “Investing in comprehensive exploration will offer an enhanced look at the potential these bodies of water offer to bolster our economy and inform efforts to protect one of America’s greatest natural resources.”

The bill’s prospects in the upcoming session are unclear under President-elect Donald Trump. While he’s distanced himself from Project 2025, the Heritage Foundation document states the agency tasked with mapping the Great Lakes should be “broken up and downsized.”

While mapping continues, Boehme said more is known about the surface of the moon and Mars than the bottom of the Great Lakes. Partners will seek to raise funding to support the Lakebed 2030 initiative.

“I would love to see folks get excited about the idea that there’s wonderful exploration opportunities right here in the Great Lakes region,” Boehme said. “All of the excitement that we saw when NASA first landed on the moon, I would consider us highly successful if we could generate that kind of excitement here.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.