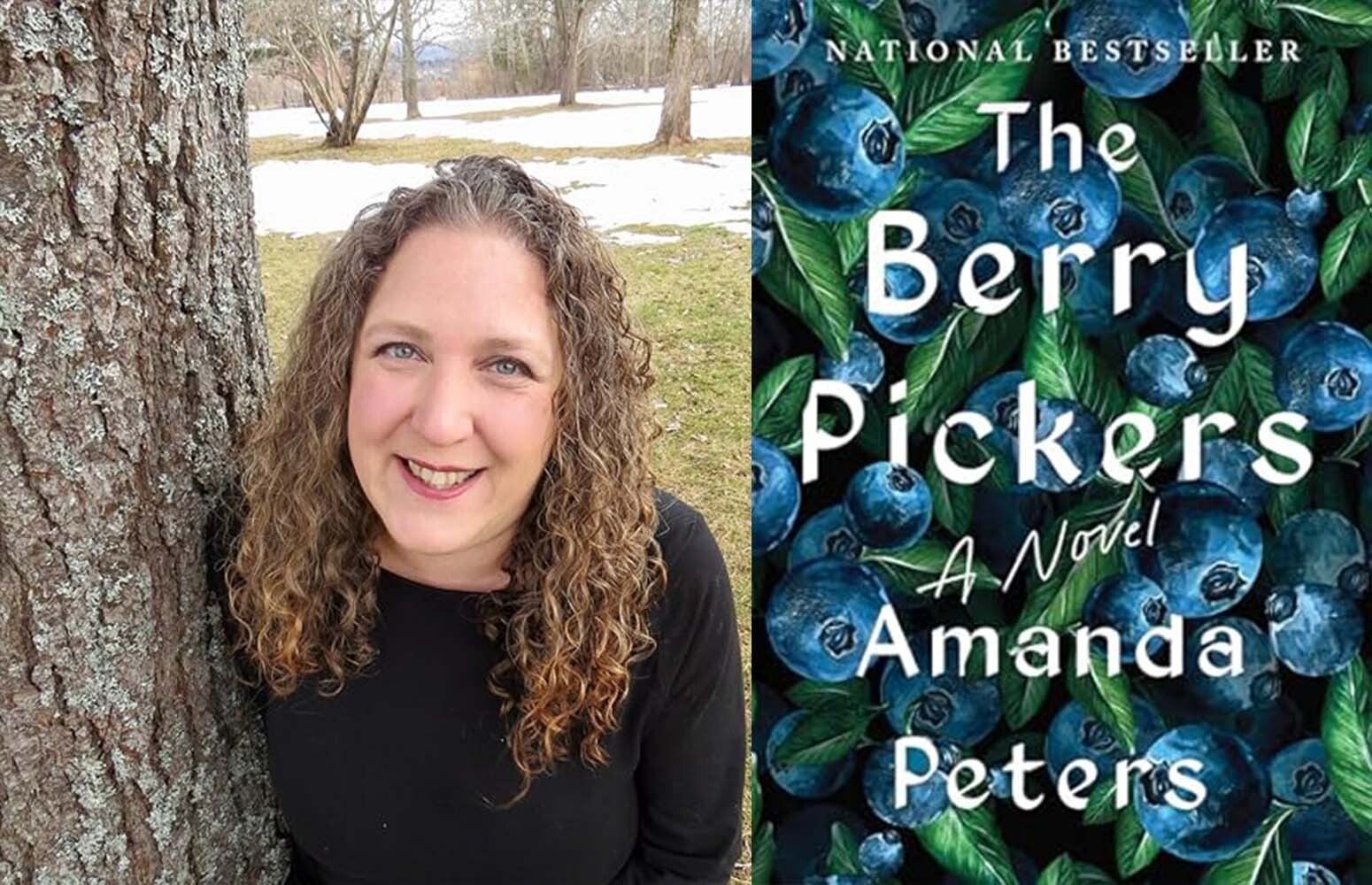

WPR’s “Chapter A Day” is bringing audiences a novel that examines how two families are changed forever after a young girl disappears.

“The Berry Pickers” by Amanda Peters follows Joe and Norma starting in 1962. Joe is a 6-year-old Mi’kmaq boy who is the last person to see his little sister before she vanishes near a berry field. Her disappearance haunts Joe for decades. Meanwhile, Norma grows up as an only child in a white family in Maine. For years, she grapples with vague memories of an unrecognizable life and a sense that her parents are keeping a secret.

The book won an Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Chapter A Day” readers Norman Gilliland and Michele Good had an opportunity to ask Peters questions about the book and about broader issues facing Indigenous people.

Editor’s note: This conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Norman Gilliland: Congratulations on the success of your debut novel! When did you decide to write it?

Amanda Peters: Wela’lin (Thank you). I am so pleased at the reception “The Berry Pickers” is receiving. I started it in 2017 after a trip to the Maine blueberry field with my father who used to pick berries with his family when he was young. I was never sure it would be a novel. For a time, I thought it might be a short story. But the story was begging to be told. It took me four years total to finish it and get it to where I was comfortable with sharing it.

NG: At what point did you decide to tell this story with two narrators of different genders?

AP: Originally it was meant to be a first-person narrative from Joe’s perspective. But after writing a few chapters, I felt the need to write Norma’s story. She was this little voice in my head asking me to let her tell her story. So, I did. I still wrote most of Joe’s story first and then wrote Norma’s and put it together like a puzzle.

NG: What kind of response to your novel have you received from your Mi’kmaq family and acquaintances?

AP: It’s been lovely. My family is so incredibly supportive of the book, and they have read it. When I set out to write it, I never anticipated that it would get the positive reaction. I wanted my mom and dad to be proud, and they tell me they are.

I recently attended a Zoom book club with Mi’kmaq book readers. They were incredibly supportive and had personal stories that they could relate to the book. It was so nice.

Michele Good: I am not Mi’kmaq, and yet there was so much about these characters that I could relate to — the loss of a child, divorce, death of a parent. These are raw human experiences. At the same time, your Native culture is very much engrained in the book — the book’s tone, Norma’s connection to place and nature, the very fact of the characters themselves. Who were you hoping to reach with this book?

AP: Ultimately, I just wanted for a person who stumbled upon it to think it was a good story and worth their reading time. Now that I have some distance from it, I’m really intrigued by those readers who reach out and tell me their stories and how they related to the story. Also, I am grateful that, in some small way, the book is contributing to the discussion on missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

NG: What sort of struggles have you had in being both of Mi’kmaq and European heritage?

AP: I wouldn’t necessarily use the word struggle but instead uncertainty. Uncertainty into how I fit in with both sides and even if I did. As I get older, I am becoming more comfortable in my own skin. I think my writing has been an integral part of that realization.

This is perhaps why I relate to Norma in some ways. She always knows that something is a bit off and never really feels like she belongs. I can relate to that a little bit. I do honor both sides of who of am, and I am proud of both.

MG: It’s hard to look past the parallels of Norma and Ruthie’s story and the broader context that white settlers took thousands of Indigenous children from their parents and forced them into boarding schools across this country and Canada, even through the late 1960s. What do you hope people learn from the story you’ve crafted?

AP: The ripple effect and the consequences of taking children from their families and their culture. As I mentioned above, this is a conversation that needs to be had. We as a society need to acknowledge the damage done and ensure that it doesn’t happen again.

MG: Before we aired your book on “Chapter A Day,” I reached out to you because both readers, Norman Gilliland and I, are white. We wanted you to know that before deciding to move forward with our airing the book. What did you consider when making the decision?

AP: The respect you showed in asking me. The thought you gave and the way you were willing to work with me. I appreciated it and made me feel comfortable with you reading.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.