The Bayfield School District is launching an Ojibwemowin Immersion Program for kindergarten students this fall as part of supporting language revitalization efforts with the Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

District administrator Beth Manidoo Makwa Paap said school officials have been discussing the program with the Red Cliff tribe for a couple years. The district of roughly 420 students is one of the few in Wisconsin where the vast majority of kids — 69.2 percent — are Native American.

“I can’t understate how significant this is — not only for our community in our area, but for our children and their future,” Paap said, who is a Red Cliff tribal member. “Cultural identity has been something that the federal government has worked really hard to strip away from Indigenous people, and the fight continues to reclaim identity and lifeways.”

Prior to the beginning of the school year, around a dozen families had submitted papers to enroll in the program. A mix of Native and non-Native youth will take part.

Binesiikwe Edye Washington, the tribe’s education division administrator, said the district intends to expand immersion programming to K-5 students at the classroom level by adding a grade each year.

“Students would be learning all content areas through Ojibwe language — anywhere from reading math, singing, games, all of those things,” Washington said.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

Paap said the immersion program will also include aspects of Ojibwe culture. She noted students at the district have already been studying how to harvest and process wild rice, or manoomin, for the last four years.

Students enrolled in the program would receive formal English instruction beginning in the third grade. The district noted that research shows immersion students have similar or better outcomes on standardized tests by the fifth grade.

Few remain nationwide that speak Ojibwemowin as a first language

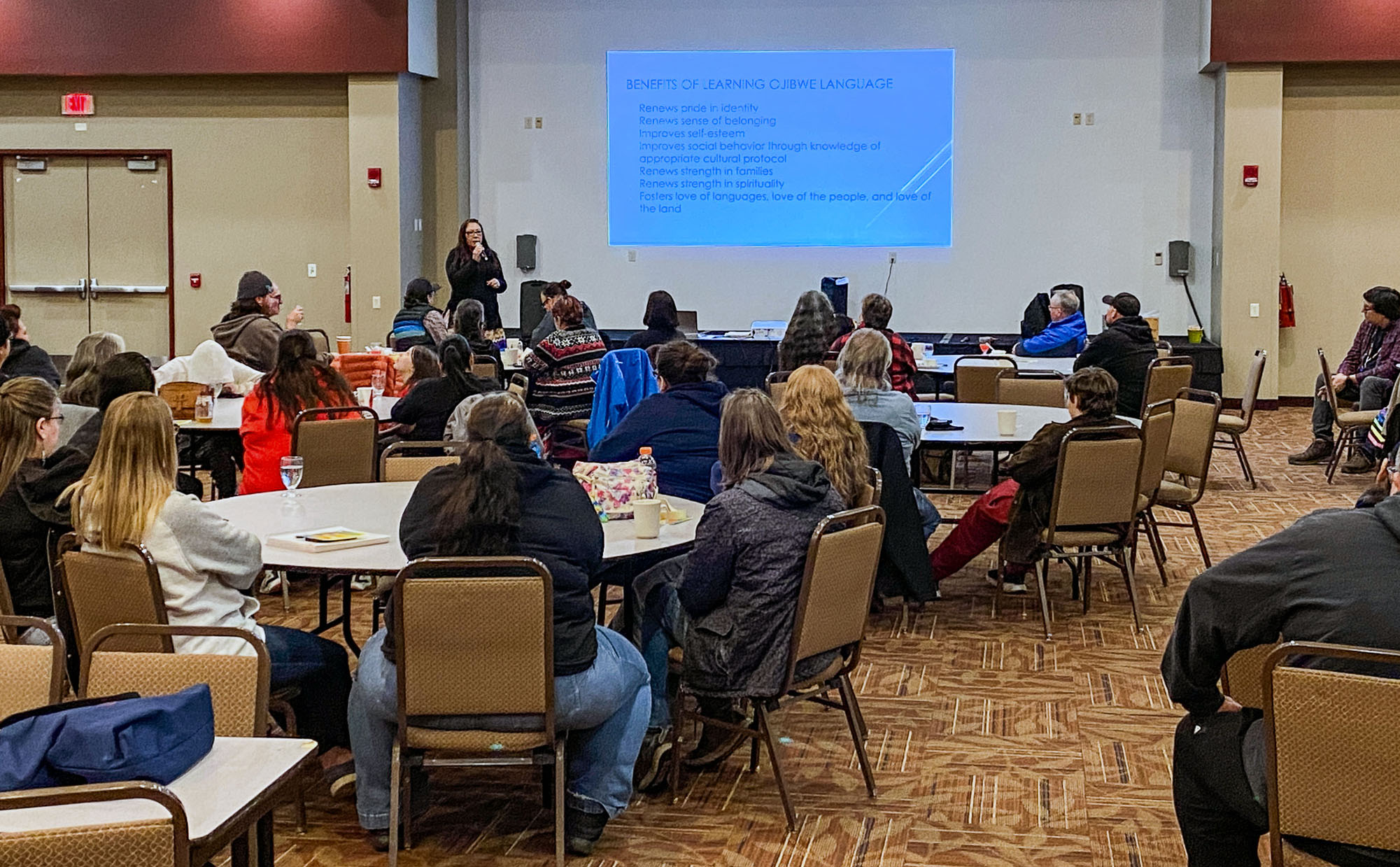

As of 2010, census estimates show almost 8,400 people could speak the Ojibwe language across North America. Officials with Bayfield Schools and the Red Cliff tribe have been working with the Minnesota-based Midwest Indigenous Immersion Network on efforts to revitalize language.

Gimiwan Dustin Burnette, the group’s executive director, first began working with the Bad River tribe as an instructor for its adult language training program in 2020. In late 2021, the Red Cliff tribe announced the creation of a three-year adult language learning program with the goal of training teachers to be fluent in Ojibwemowin. For the past two years, Burnette worked with a cohort of trainees from both tribes.

He said language revitalization efforts are significant since only about 60 or fewer people remain in the U.S. that speak Ojibwemowin as their first language.

“Language revitalization is incredibly important as it instills and furthers the development of an individual’s identity and connection to themselves, where they live, their home and their community, their spirituality, all of the above,” Burnette said.

Ojibwe immersion programs have grown in the last decade

Burnette also taught at Waadookodaading on the Lac Courte Oreilles tribe’s reservation. He said it was the only Ojibwe immersion program in the Midwest when it began more than two decades ago. Now, he said there’s more than a dozen in the region.

“We have really grown significantly, especially over the past 10 years,” Burnette said.

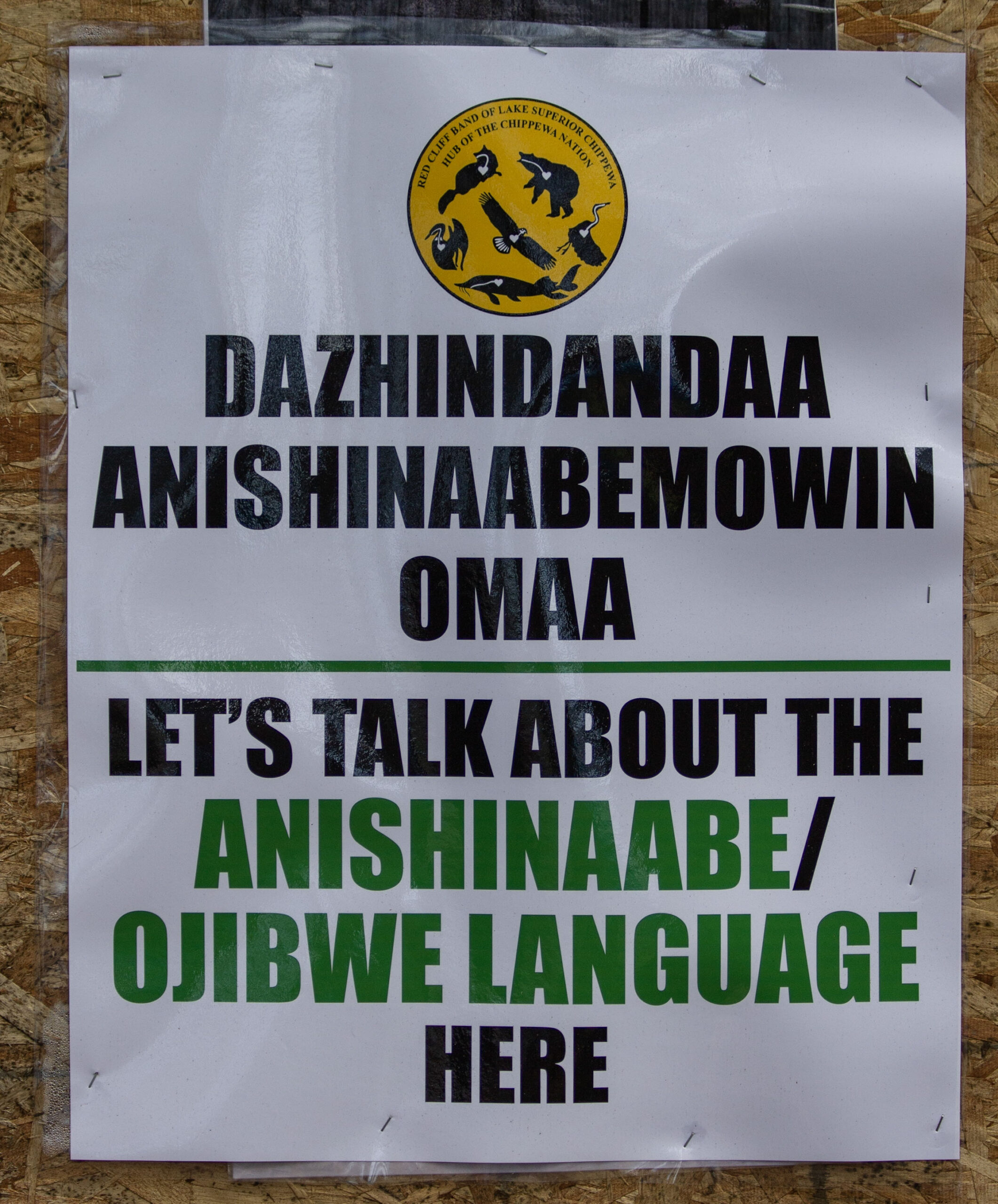

In 2020, the Red Cliff Tribal Council passed a resolution declaring Ojibwemowin as the tribe’s official language, and it approved a five-year plan to preserve the language within their community.

Washington previously worked with Duluth Public Schools to launch its Misaabekong Ojibwe Immersion program. She said the program launched at the Bayfield School District means a great deal not only to the Red Cliff tribe, but all Ojibwe communities.

“If you think historically about the education system in general, and the negative impact it has had on Indigenous people through boarding schools and other historical traumatic events, turning back to teaching our students through our language and our cultural lens — I think it will and it has had a very positive impact on our communities,” Washington said.

Forced assimilation led to loss of language for many tribes

Beginning in the early 1800s, federal policies supported the establishment of Indian boarding schools that sought to remove Native American children from their families, languages and cultural beliefs. Wisconsin had 11 Indian boarding schools, including the Bayfield Mission Boarding and Day School.

Also known as the Holy Family Mission School, it was established in 1880 and closed in 1999. In an 1889 report, the school’s superintendent said having Native youth attend the day school with white children was a “great aid in civilizing the children and entirely abolishing the use of the Chippewa language.”

When she was growing up, Paap said the Ojibwe language was often hidden or suppressed and rarely spoken in her home.

“We didn’t have Ojibwemowin spoken at home aside from a couple of words and phrases here or there,” Paap said. “I think that’s why this revitalization is so profound. We are kind of reclaiming what was really taken from us for so very long.”

Paap said they will provide resources to families, including language tables, to help them support the use of Ojibwemowin at home.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.