Ann Mader wakes up before the sun. She laces on hiking boots so she can hike unstable ground. And then she drives over to the American Family Insurance headquarters in Madison.

Once she arrives, Mader begins walking the campus, looking at the ground. She passes three employees, and sees what she was searching for: a dead bird. By their feet.

“Ope! They just walked right by that,” Mader says.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

She takes pictures of the dead bird and the windows above it. It is a Swainson’s thrush, a hand-sized migratory brown songbird with a spotted breast, known for its melodic songs. She thinks she sees a smudge on a window where the bird hit. Then she pulls out gloves and a plastic bag, gently picks up the bird and sets it in a bigger canvas bag, alongside two other dead birds she found this morning.

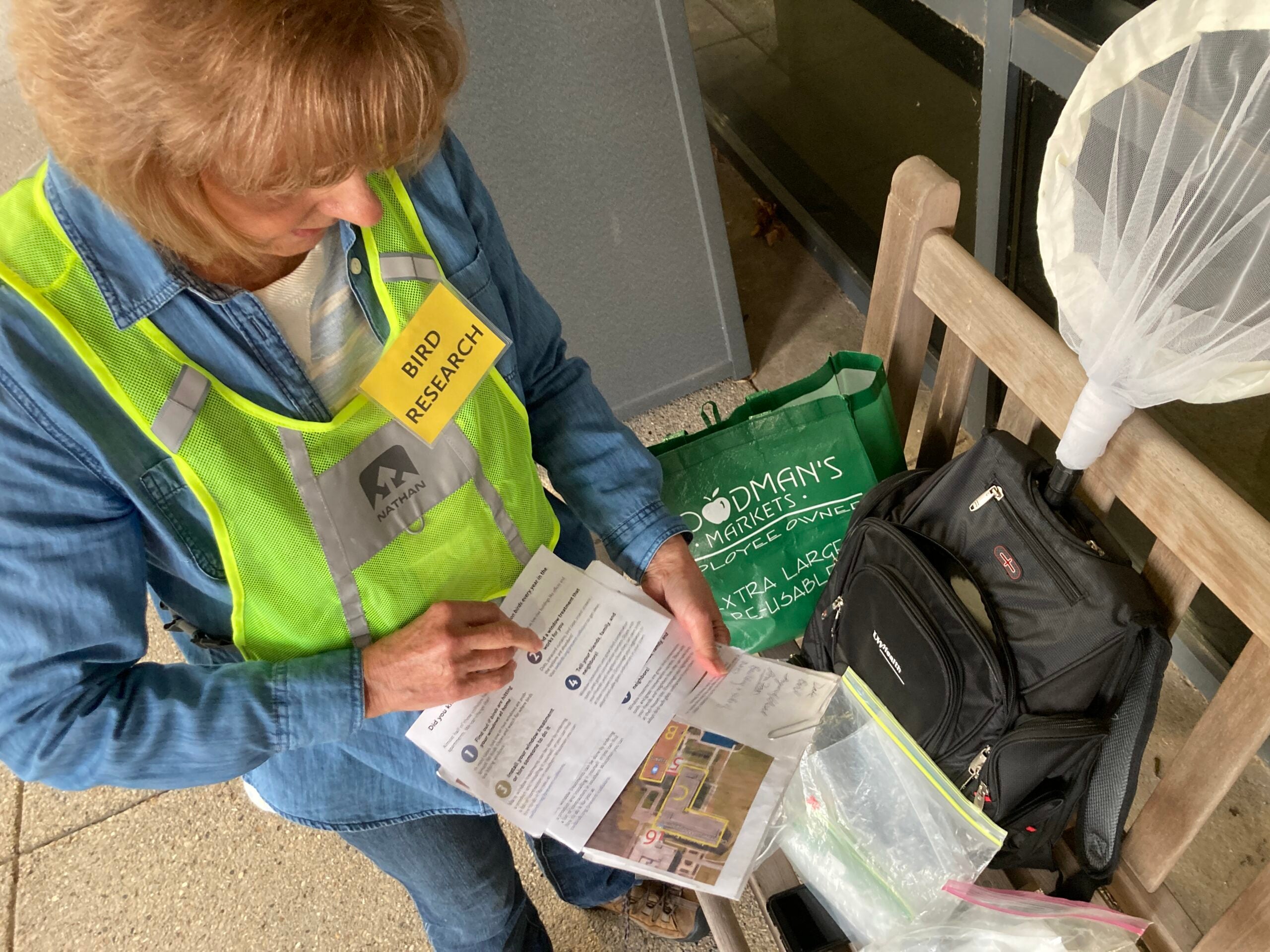

Mader, of Cottage Grove, is part of the Southern Wisconsin Bird Alliance’s “Bird Collision Corps,” a team of volunteers who survey birds that have died from window strikes.

They track the number and type of birds that have died at over a dozen sites in and around Madison, almost every day. Their goal: to identify high-risk windows at each site.

On a wider scale, the alliance wants to help a struggling migrating bird population by persuading Wisconsinites to update their windows and policymakers to pass regulations that require building owners to follow best practices for mitigating bird deaths.

“If it makes a difference, if it improves things, it’s worth it,” Mader said.

Mader, a volunteer, will survey birds three times a week for six weeks, from Sept. 16 through Nov. 1. These are generally the heaviest weeks of fall migration season for birds in Wisconsin, which can go from late July to early December.

Fall bird migration in Wisconsin can bring broad-winged hawks gliding on thermals in the Mississippi River Valley and loons coasting on Madison’s Lake Mendota and Lake Monona. The long migration season kicks off each year with shorebirds coming down from the arctic in July, followed by songbirds in September and waterfowl, like swans, in late October. Eagles move south in late November.

As migrating birds fly south through Wisconsin, they encounter hazards that can be fatal — such as cats, wind turbines and windows.

Window collisions are a top threat to migrating birds

Mader has been a self-proclaimed “bird nerd” since she was a kid. She grew up on a dairy farm between Eau Claire and Menomonie, and had relatives who would visit to bird-watch. She and her husband went bird-watching for their first date. Later, they had bluebird boxes in their backyard. And in 2020, when Mader retired, she signed up for the Collision Corps.

“It’s kinda rough at times,” Mader said. She recalls picking up a dead black-billed cuckoo, which she’d never seen in Wisconsin. “Of course, they were migrating through.”

“I unfortunately see birds close up this way more than I do when they’re alive,” she added, with a dry laugh.

Organizations around the nation have similar teams that track bird collisions. They are one of the leading threats to bird populations. According to a widely cited 2014 study, between 365 million and 988 million birds in the U.S. die in building collisions each year. The human-made hazard is second only to cats, which kill between 1.3 billion and 4 billion birds in the U.S. per year, according to a 2013 study in the journal Nature Communications.

“Birds came before windows,” said Carolyn Byers, the director of education at Southern Wisconsin Bird Alliance. “They haven’t been able to evolve to deal with windows. They don’t understand glass so they crash into them a lot and that’s a big hazard for them.”

Byers said migrating birds are particularly vulnerable. They can encounter windows because they’ve been pulled into a city by lights. Scientists aren’t quite sure why, but bright lights attract the birds. Most birds migrate at night, and use the stars to navigate.

“They can become disoriented, and they’ll fly towards the bright lights rather than continuing on their path,” Byers said.

Over time, hazards like these lights and windows are taking a toll. A nearly 50-year study of birds in North America found that populations have shrunk across species, by billions. Avian ecologist Anna Pidgeon has seen this in action. She’s been studying birds at the University of Wisconsin-Madison for over two decades.

“I certainly have noticed fewer birds in the air,” said Pidgeon, who also said it is just a coincidence that her last name sounds like the bird, pigeon.

She said over one-third of America’s migratory bird species are at risk. Climate change is affecting them too. With extreme weather events happening more often, birds can get thrown off course. For example, Pidgeon said early springs are happening more frequently in Wisconsin. That means flowers bloom early, and bird food like caterpillars may peak before the birds arrive. That can be a problem for long-distance migrating birds, who use day length as their cue for when to migrate.

“There’s a mismatch between the young needing food and the food being abundant and available,” Pidgeon said.

Taking action can reduce risk to birds

But she said there are many things Wisconsinites can do to help the migrating birds, such as turning off unnecessary lights at night, planting native plants on their property and keeping outdoor cats in screened-in “catios.” She knows keeping cats inside isn’t popular advice, but asks people who let their cats roam to reconsider.

“Cats are a huge, huge problem, (and) also a politically sensitive problem,” Pidgeon said. “We feed them, we vaccinate them, and then we turn them loose and they wreak havoc.”

Local organizations also work on educating the public about threats to birds. Byers, in her role at Southern Wisconsin Bird Alliance, runs regular nature education programs at Madison public schools. One activity they do is a migrating bird obstacle course. Kids pretend to be birds, trying to make it south while avoiding hazards.

“We always have a child pretending to be an outdoor or feral cat, and so they’ll be tagging kids as they’re running by,” Byers said.

By flagging problem windows, volunteers have helped make changes

On her mid-September rounds at American Family Insurance, Mader found three migratory birds that seemed to have died by colliding with windows on site. The campus on the east side of Madison is a series of glossy buildings, connected by skybridges and surrounded by prairie.

When she first began surveying, there was one place Mader dreaded more than any other. From 2020 to 2023, Skybridge 6 at the American Family campus was a hotspot for dead birds. One time, she recalls finding at least eight of them there.

“This is where I used to cringe, coming around here,” Mader said as she approached the spot.

But Skybridge 6 is no longer a trouble spot, and that is the result of a concrete action taken by the insurance company. It’s proof that the work Mader is doing to collect these data is having an effect. In 2023, American Family Insurance put dot stickers on Skybridge 6’s windows, to deter the birds. Mader’s team has only found one bird there since.

“It’s just amazing what that’s done to help prevent bird collisions,” Mader said.

Landscape architect Wayne Rayfield works for the company and helped it become a Collision Corps site.

“We knew this was a problem, even before we were part of the program,” Rayfield said. “We’d find dead birds, and also people would report seeing a bird hit the window.”

He said the company is discussing replacing aging windows with bird-safe ones, like other buildings in Madison. A 2020 city ordinance, passed with support of the Southern Wisconsin Bird Alliance, states all new buildings over 10,000 square feet in Madison need to have bird-safe windows.

Cities and states across the nation have adopted similar mandates. In 2021, Wisconsin set bird-deterrent guidelines for state-owned construction projects.

Mader even put the dot pattern stickers up on her windows at home.

“I refuse to have a bird hit at home if I’m doing this here,” Mader said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.