About two years ago, University of Wisconsin-Madison entomologist Emily Bick went down a research rabbit hole.

She was trying to find a way to stop moths in Indonesia from destroying sugarcane crops. In her research, she learned that spy agencies used to attach microphones to walls and translate the vibrations into speech.

She wondered if she could use those methods to detect and identify pests that destroy crops in the field.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

“If we know exactly when and where the insects show up, then we can precisely target those insects,” Bick said on WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.” “We can do that true precision agriculture approach — versus right now, we tend to spray on a calendar or spray on some limited scouting data.”

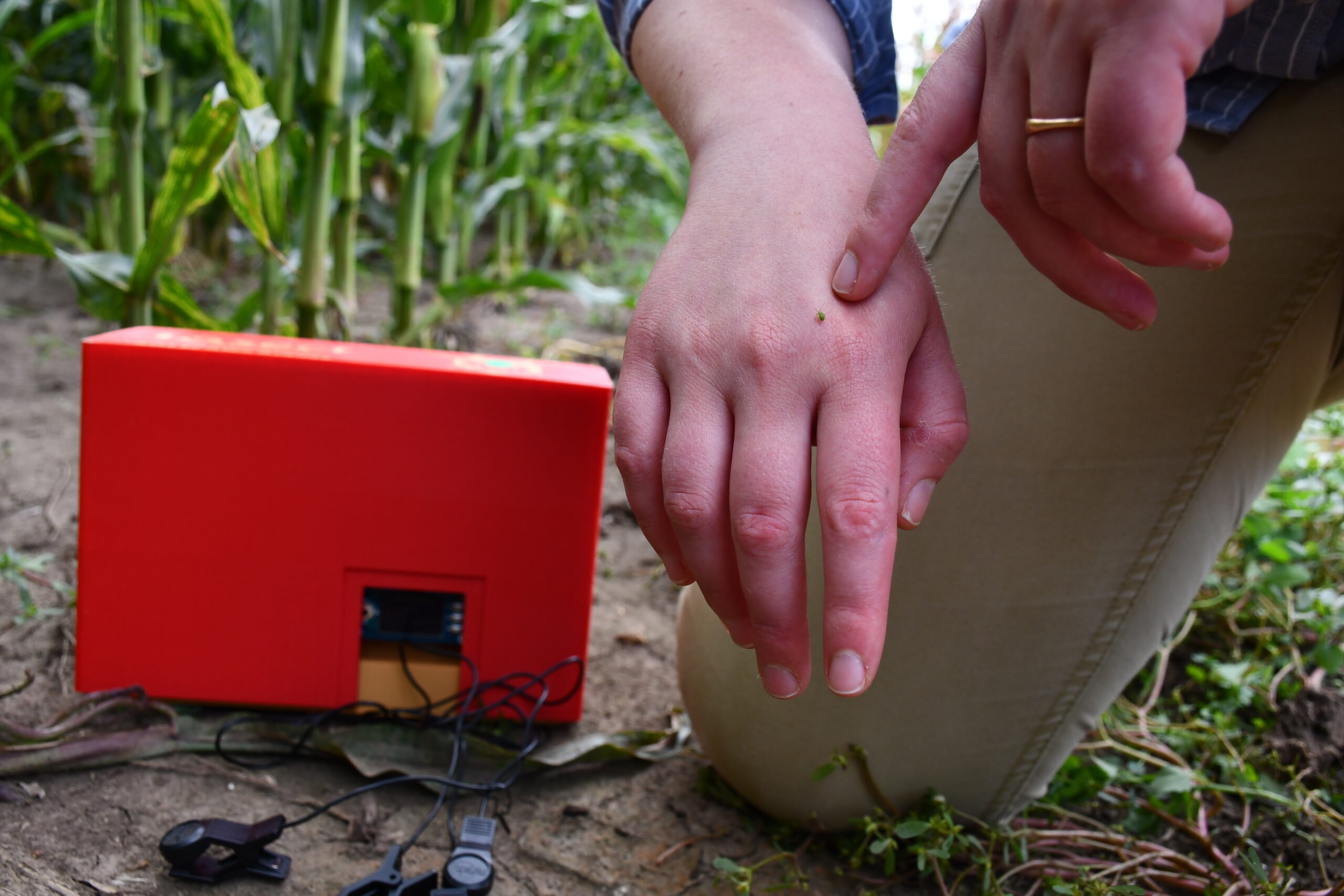

Bick then invented the “insect eavesdropper.” The device attaches to crops and records the sounds of pests. She spies on the insects as they damage crops like corn and soybeans.

She has bugged the bugs.

As some of these pests eat the crops from underground, the recordings aim to tell researchers information without removing the crop from the soil.

Researchers are looking for what type of insect is eating the plant, population density and at what times of day the insects are most active. In the future, Bick and other researchers hope the sounds can help identify if an insect is infected with a disease.

Her “eavesdropping on insects” project recently received a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. It was among 14 projects sharing $7.4 million in funding.

Between 20 and 40 percent of global crop production is lost to pests annually, according to the federal agriculture department, which also reported that each year, plant diseases cost the global economy about $220 billion, and invasive insects around $70 billion.

Bick’s team is studying the effects of beetles on soybeans and potatoes, as well as northern corn rootworm on corn.

Corn rootworms are known as the billion-dollar bug because of the amount of damage it causes, she said. Effective treatments are limited.

Listen to the sound of the northern corn rootworm as it munches on a corn plant.

That sound is of the corn rootworm larvae using its maxillary palps or sensory organs to bang and crunch on the corn plant. The banging helps the insect determine if there is enough sugar or if there are some chemicals in the plant that the insect wants to avoid.

The larvae are about 5 millimeters long, Bick said.

She teases apart the sounds, sometimes using machine learning. If researchers can determine when the insects are most active, it will help reduce the amount of pesticides farmers use and save more crops, she said.

“You have this major piece of interaction time where that pesticide or that good bug needs to be at the right place, at the right time,” she said. “If you don’t know when that right time is, you could be expressing (the pesticide or biological control agent) at the wrong time so that the insect just won’t encounter it.”

What researchers learn from pest sounds can be useful for different types of pest management, including synthetic chemicals, pesticides used on organic farms, and biological control management, which uses natural enemies to suppress pests.

Entomologists have been using microphones for more than a century, she said. She believes cost is what sets her device apart.

The “insect eavesdropper” costs about $120 now, and Bick hopes to eventually reduce the price to $15. Other sound detection devices can cost thousands of dollars. Bick once worked with a sensor that cost $30,000.

Right now, 20 academic labs and three agriculture companies are testing out the product, she said. Ultimately, she wants it to provide more sustainable food growing practices.

“The hope is that this type of sensor can directly serve the folks in the state of Wisconsin,” she said.

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.