In the late 19th century, Milwaukee County resident Jennie Sharpless died of malnourishment at age 2. Her body was buried in the “poor farm” cemetery, along with thousands of other indigent people.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Wisconsin, like other states, had institutions that took in people with no other place to go. Sometimes the people had disabilities or were unwed mothers. Sometimes they stayed for days or years. These institutions, often run by the county, were known as poor farms.

Today, more than a century later, Sharpless’ great-niece, Judy Klimt Houston, is determined to finalize the exhumed ancestor’s resting place — and that of the people once buried around her at the county grounds.

News with a little more humanity

WPR’s “Wisconsin Today” newsletter keeps you connected to the state you love without feeling overwhelmed. No paywall. No agenda. No corporate filter.

“Our hope is to restore dignity, respect, provide closure and just realize that these people (had) lives,” Houston said on WPR’s “Wisconsin Today.”

The people Houston referred to are known as “The 831.” Archaeologists exhumed their remains from the Milwaukee County Grounds cemetery — known as “Cemetery 2” — in 2013 to make room for the Froedtert Hospital Center for Advanced Care.

Since then, The 831 remains have been shelved at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee for anthropological research. Some of that research involves osteological profiling to identify individuals, any trauma or health issues and if possible, gender and age.

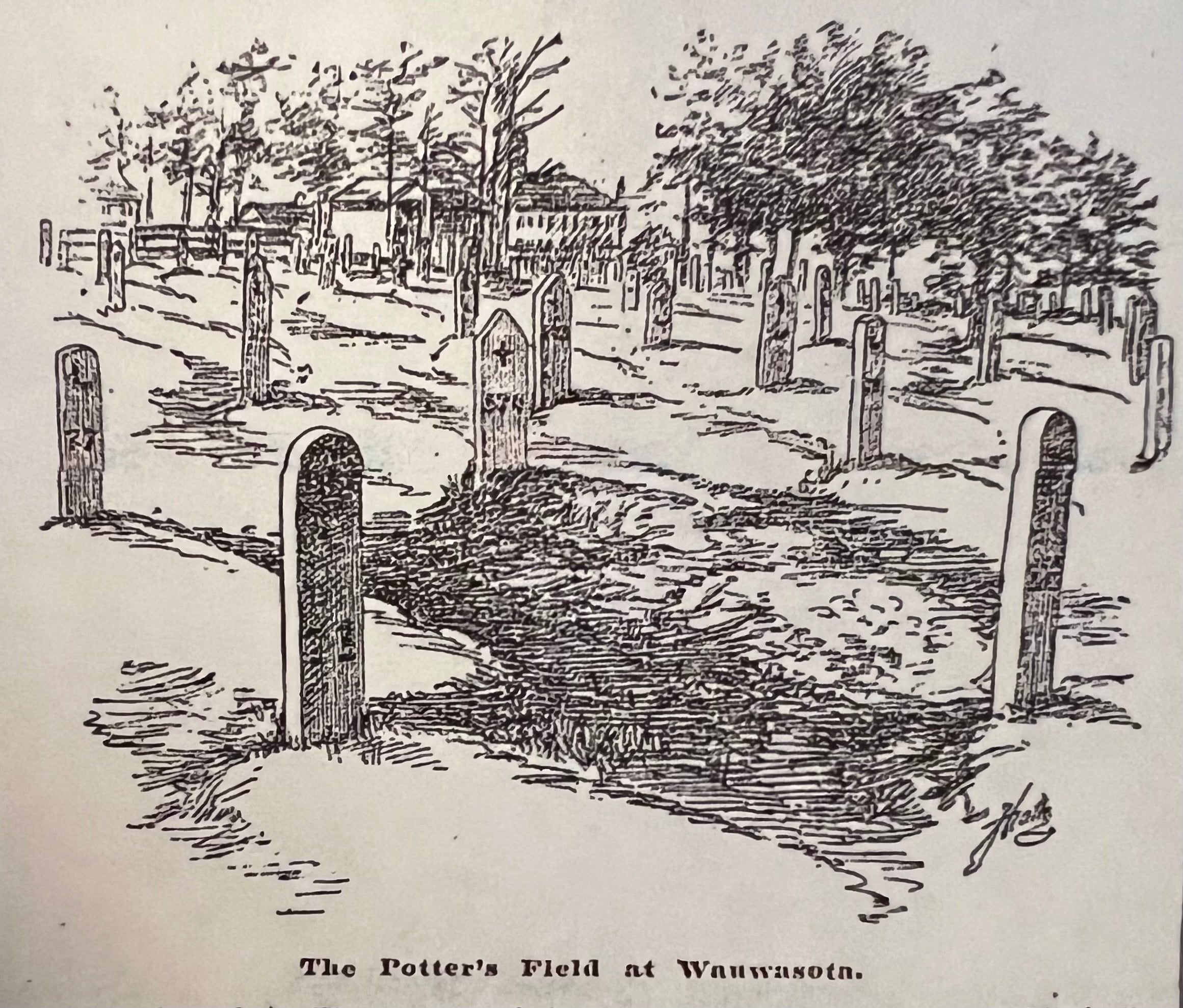

Houston founded and leads The Descendant Community of Milwaukee County Grounds Cemeteries, a nonprofit that supports families of the roughly 10,000 people who were once buried at four different cemeteries across Wauwatosa.

Genealogists have helped identify and memorialize some of the people once buried at these cemeteries. The organization has even identified ten soldiers from the cemeteries whose lives spanned the Civil War to the Spanish American War.

“We’ve been able to reestablish them in the community,” Houston said. “We applied for their VA headstone(s) so that they are finally recognized for that service,” she said.

Cemetery 2 had about 7,200 graves. Several years after the last burial in 1925, Milwaukee County prepared the grounds for construction, destroying about 55 percent of the graves.

Construction workers used soil from the cemetery for backfill. Houston said they’re still finding remains on the grounds today.

Earlier this year, the Wisconsin State Historical Society awarded The Descendant Community disposition of the remains — meaning authority to reintern them according to the community’s proposal. The group hopes to bury the remains in three-foot graves at the Forest Home Cemetery, Houston said.

Houston expected re-burials to start in November. But the cost — and who’s responsible for paying — are sticking points.

As the disturbing entity, Froedtert should be responsible for paying for the reburial of the remains, according to the historical society.

However, Froedtert and Milwaukee County filed an appeal to the historical society’s decision. In the appeal, Froedtert said the reburial will cost between $3.5 and $4 million.

The next step is a pre-hearing conference scheduled for January.

In the meantime, Houston and the organization continue to try to connect ancestors with their descendants and tell the stories of people once buried at the cemeteries.