Kim Robinson and his brothers had a running joke with their dad, an architect, about his choice to work in Milwaukee.

“We’d say, ‘Hey dad, why didn’t you go to Illinois, in Chicago, and build skyscrapers there? You’d have made a lot more money,’” Robinson remembered.

“Because back then, in Wisconsin and Milwaukee, there was a lot of racism and discrimination,” he explained.

Stay informed on the latest news

Sign up for WPR’s email newsletter.

His father, Alonzo Robinson, who died in 2000, was the first licensed Black architect in Wisconsin.

On Monday, Alonzo Robinson’s Central City Plaza — a former Black-owned, Black-developed shopping center — got one step closer to historic status after a vote by Milwaukee’s Historic Preservation Commission.

The Salvation Army currently owns two of the plaza’s three buildings. It runs its homeless shelter out of the larger one. It had filed raze permits for the plaza’s smallest building in late 2024 as part of those plans.

But that property got temporary historic status in January after a campaign by preservationists.

Now, the entire plaza is on track for historic status after five out of commission’s seven members voted for it at Monday’s meeting.

The Milwaukee Common Council still has to confirm the status. If it does, any new development on the site would likely have to preserve existing structures.

“If these properties are designated as historic, the parameters and boundaries that puts on us as a nonprofit organization are immense,” said Rachel Stouder, general secretary of Wisconsin’s Salvation Army, at the commission meeting.

She said her chapter had to turn down a donation of 120 hospital beds because they didn’t fit through doorways at the current shelter.

At the meeting, commission member Matt Jarosz argued that historic status wouldn’t kill the Salvation Army’s plans.

“We can really work together to retain the spirit and the quality of that place but still make it usable,” he said.

Architecture, Black history behind plaza’s designation

The idea behind a Black-owned shopping center, as Kim Robinson remembers it, was simple: “Let’s develop something of our own.”

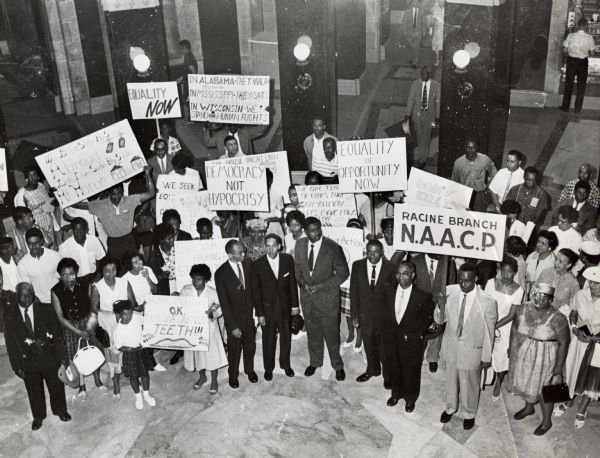

The complex opened in 1973 in a majority-Black area near downtown Milwaukee. Its lead developer was Felmers Chaney, a bank president and leader of the city’s NAACP chapter.

Its Black-operated shops included a bowling alley, pharmacy, supermarket, legal and psychiatric offices, and a restaurant serving “veal cordon bleu as well as soul food,” per a 1973 Milwaukee Journal article provided by Kim Robinson.

Alonzo Robinson designed the plaza in a concrete-based New Formalism style, according to preservationists’ historic status application. The document notes the smallest building’s porthole-like windows and the other buildings’ arched entryways.

Kim Robinson calls those arches “wings,” a signature of his father’s work.

“It gave the building wings,” Kim Robinson said. “It opened up the building to people.”

Alder Robert Bauman, who chairs the preservation commission, said the body’s historic status criteria are “overwhelmingly satisfied” by the plaza.

Robinson’s legacy dots Milwaukee cityscape

Kim Robinson said his father often worked for Black business owners and church congregations who got turned down for not paying enough.

“No white architects would take it on,” he said.

He designed the Pilgrim Rest Baptist Church and Mount Carmel Missionary Baptist Church, which recently got a grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

His portfolio also includes the Milwaukee Fire Department’s headquarters, now named after him.

Another client was a young man opening a neighborhood grocery store — Fast n’ Friendly on Locust Avenue and MLK Drive.

Recently, Kim Robinson went there to buy a bag of ice during Juneteenth celebrations.

“I believe my dad designed this building back in the day,” he remembers telling the owner, who still worked at the store he built decades earlier.

“Yes,” he said the owner replied. “Your dad Alonzo was a blessing to me because when no one else would do the work for me, your dad would do it.”

Wisconsin Public Radio, © Copyright 2025, Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System and Wisconsin Educational Communications Board.